One of the major glaciers, the Kolhai in the Pahalgam Mountains is fast receding. While the blame goes to climatic change, nobody in the government is looking at visible biotic interventions that are gradually depriving waters of the vale, reports Umar Khurshid

Majid Ahmed, a student of a Government Degree College, is a frequent trekker to Kolhai Glacier. In 2010, he went up for the first time. This summer he is on the glacier, for the fourth time.

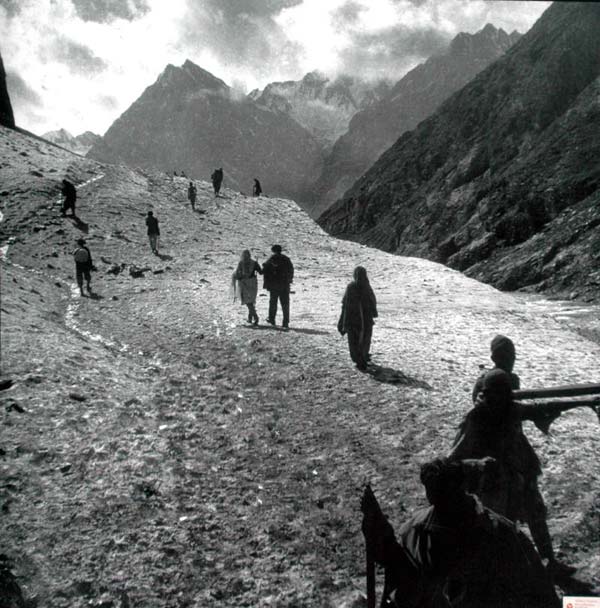

“I see the rapid changes,” Majid said. Accompanied by friends Adil and Suhaib both 23, when Majid reached Satlanjan, the base camp for trekking saw a marked shrinkage.“Last year where we started the ice trek was dry this time.” The shrinkage is physically verifiable, year after year.

Majid usually accompanies the trekkers from Jawahar Institute of Mountaineering (JIM), and every year he measures the shrinkage in meters. “Even shepherds or nomads spending nights near the glacier and disturb the environment by lighting up huge fires,” he said.

Mohammad Umar, 28, runs a photo lab and usually goes to Kolhai for photography. “There are cracks in between the glacier which melts due to the vibrations of helicopters flying pilgrims to the Amarnath cave,” Umar said. “I feel there is a rapid increase of shrinking and it can be dangerous to human life.”

Sajad Ahmed 35, lives in the picturesque Aaru valley and is a frequent visitor to Glacier. “This glacier is the main source of water and if it disappears, what will happen to Kashmir?” he asks, insisting the people must start thinking. “Are we gradually getting into a desert?” Residents say the glacier extended down the river bed earlier. Now it is kilometres away as the river bed is dry.

It was 6 am and Majid with his two friends left for the glacier. He is accompanying thirty trained JIM students. “Today we will dig snow pits on the accumulation zone, at the starting of the glacier,” explained the JIM trainer, as he strapped ice clips to his boots. “If you have more water going out than what is coming to it, the shrinkage of the glacier is seriously affecting it and the life around.”

Majid and his two friends lack any scientific experience to trek to the accumulation zone, but the trio has played a vital role in collecting data on the lower portions of the glacier known as the ablation zone or the area where the ice melts. The rapid changes in the mass of the glacier have already started impacting the human life around.

The nomadic Bakarwals, goat-herder, who bring thousands of sheep for grazing in the Liddar Valley, have dealt with unpredictable water fluxes in recent years. “We used to know when the waters would be in the river,” said Shafi, an aged Bakerwal. “ But now the waters are too high or too low. We cannot expect what happens and when. This way of life is no good anymore.”

Mohammad Yasin 32, from Aaru, associated with Shafi for cattle grazing. He said there are almost 15 glaciers including Kolhai, some of which, have completely disappeared. “I do not know, how to react to it.”

Located over the peaks between Sonamrag and Pahalgam, Kolhai feeds the Lidder river and contributes its glacial melt to various small streams which eventually join Sindh. It has reduced from 13.57 sq km to in 1963 to 10.69 sq km in 2005. Various accounts suggest that the climatic change induced by clear biotic interventions has hollowed it making it all the more dangerous. Many experts call it a hanging glacier.

“The composite results show that the glacier has receded by 3423 m (21.8 m/year) in the past 157 years, a joint study Dimensional changes in the Kolahoi glacier from 1857 to 2014 by four experts including Prof Shakil Ranshoo said in 2016. “The historical records reveal that the glacier retreated by >1609 m from 1857 to 1909, 800 m from 1912 to 1961, and 210 m from 1961 to 1984. From 1962 to 2014 (52 years), we observed a retreat of 1014 ± 64 m (19.5 ± 1.1 m/year).”

Kashmir valley’s only year-round source of water, The Economist reported in October 2008, is in “dirty brown colour, wrinkled with crevasses” and “looks more like an enormous mudslide than a frozen reservoir of fresh water”.

Mushtaq Pahalgami 38, lives in Pahalgam. He is associated with the hospitality sector and is an environmental activist for the last eight years. “ “If no step is taken to save the glaciers then probably there will be no glaciers after 15 years in Kashmir,” Mushtaq said. “We try to educate people but we have our limitations.”

“Nomads go with their herds near the glacier, light up the fires and the immense smoke not only pollutes but effects on glacier also,” Mushtaq said. “They do not have an option. Why can’t a state government provide them solar lights so that there are no bonfires or smoke near the glacier?” In Ladakh, Mushtaq said, half of the cleaning of the tourist spots is done by residents. Why cannot we do?

Suhaib Ahmed 23, a third-year BCA student, had his first trek on Kolhai with JIM in 2010. “No one knows the depth of the glacier but one can make out it easily by the decreasing width of the snow monster.”

Dudsar and Hukhsar are the two rivulets flowing on either side of the glacier. A few years back, they were too small but they have grown bigger. “The waterfalls are clearly depicting the crisis of the glacier,” he said.

Adil Malik 23, a former Mountaineer remembers accompanying his father, who told him tales of an unending Kolhai and two rivers flowing near it. “No one was allowed to talk during the trek (fearing) a slight vibration can create crevasse on it,” my father used to tell me, insisting that the glacier was connected with the rivers by a sheet of snow. “The place where I started to climb in 2010 is dried up now, at least 10 meters glacier was dried and those ten meters are rocks, devoid of snow.”

An employee in the state’s R&B department, Mohammad Akbar 60, said Kolhai is not the only glacier that is gradually evaporating. While most of the small glaciers have disappeared, those still surviving are reduced in size by two-thirds. “Yatra is one major reason,” Akbar said, “But the policymakers must look into it and try preventing its fast melting.”

“The glacier has developed several crevasses and cracks over the years, one of the main reasons of crevasses is helicopters which overfly it,” Akbar’s colleague, Ali Mohammad said. “Vibrations deepen the crevasses.”