By: Irfan Tramboo

What happened in Kashmir in the pre-1947 era is still largely shrouded in mystery. Only once in a while, we get to see glimpses of this time period when the destiny of Kashmir was shaped. The dubious role of local leaders and the larger political battle in the subcontinent for power proved crucial for Kashmir’s future.

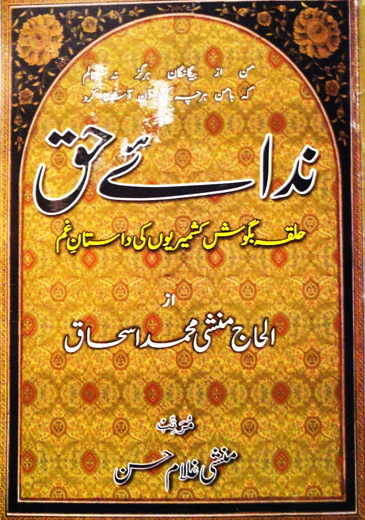

The recent release of memoir Nida-e-Haq by Munshi Muhammad Ishaq, an erstwhile companioning of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah succeeds bringing to fore some of the missing chapters of Kashmir history. Edited by his son Munshi Ghulam Hassan, a historian and scholar, Nida-e-Haq is a compilation of diaries written between 1930 and 1960, during Ishaq’s detention in various jails in Kashmir.

Disheartened by his mentor Sheikh Abdullah’s U-turns at some of the crucial junctures in Kashmir history, Ishaq founded Plebiscite Front and dedicated himself completely for the right to self-determination of his fellow citizens. What makes Ishaq’s memoir important for any historians interested in the changing political history of Kashmir in particular and sub-continent, in general, is his unbiased approach in recording the events that he was witness to. He records history for future generations and exposes the brutal nexus of National Conference (NC) and autocratic Maharaja during the pre-1947 era. Ishaq reveals the role of NC leaders in sabotaging the ‘freedom moment’ in thread bare and unbiased manner.

Though, there are some parts in Nida-e-Haq which are already in public domain like how Mirwaiz Yousuf Shah introduced Sheikh Abdullah to people at Khankahi Muala Srinagar on 21st June 1931 and how Sheikh Abdullah sidelined him gradually.

Ishaq remembers Sheikh Abdullah reading a couplet during his maiden speech and pledging to free Kashmir from foreign rule.

Ishaq remembers Sheikh Abdullah reading a couplet during his maiden speech and pledging to free Kashmir from foreign rule.

Aie khuda de dasto baazu-e-heydar hamein

Phir ulatna hai saf-e-kufur wa dar-e-khair hamien

But as Sheikh Abdullah grew in stature and emerged as the only powerful voice from Kashmir he deviated from his earlier pledge, leading to the division among leadership.

The author discusses at length how India’s struggle for independence from British rule had a parallel effect on Kashmiri freedom movement. It inspired Kashmiris leaders. But when the demand for the creation of Pakistan was raised, Congress leaders did their best to stay in contact with Kashmiri leadership. Congress wanted Kashmiri leadership to remain aloof from Muslim league. The job of keeping Kashmiri leadership in good humour was entrusted on Gandhi who visited Kashmir to persuade Maharaja to accede with India instead of Pakistan. On the other hand, Nehru was doing his bit to persuade his friend Sheikh. Ishaq records all the happenings in his memoir for sake of history.

Ishaq claims that Sheikh Abdullah and Ghulam Mohi-u-din Karra were impressed by the communist Ideology. The manifesto of National Conference, under the name of ‘Naya Kashmir’, was written under the guidance of the communist leader, BPL Bedi. Bedi, has been his (Sheikh’s) advisor for a good time.

The first textbooks for the schools were formulated under the guidance of Farida Bedi, wife of Bedi.

The name Lal-Chowk also came into being after NCs peace brigade was trained by leading communists in the ‘Palladium Talkies’.

Ishaq has also described the events wherein Muhammad Ali Jinnah came to Kashmir to pave the way for the reconciliation between the two parties, National Conference and Muslim Conference. Jinnah was forced to leave the valley after Sheikh Abdullah addressed a public rally at Khanyar and said: “He should leave as early as possible, after which we will not be responsible for his wellbeing.”

Ishaq claims that Kashmir’s accession with India was not based on any principle, it happened just because Sheikh Abdullah had some personal enmity with Pakistan.

At the same time, Sheikh Abdullah was misled by the pseudo-secularism of Nehru, who after 19 August 1953, when the situation turned ugly said ‘I will prefer to leave Kashmir as the independent country, rather than giving it to Pakistan.’

But eventually Sheikh Abdullah went ahead with his plans and signed the now controversial instrument of accession for merger with India. Interestingly Sheikh represented 40 lakh Kashmiris at United Nations Security Council and argued with Pakistani delegates heartedly. But once he was back in Kashmir he assured people that the accession is temporary, with the condition that free and fair plebiscite will be held soon.

But that never happened, Ishaq claims that New Delhi used Plebiscite as an excuse to keep people shut. Eventually in 1953, Sheikh Abdullah was ousted from power and his deputy, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad was installed as PM.

Ishaq argues that it was all pre-planned and both Bakshi and Maulana Muhammad Sayed Masoodi were part of the plan. But he claims that the plan was hatched by New Delhi to keep themselves relevant in Kashmir.

But after Sheikh’s exit situation in Kashmir worsened to the extent that Nehru was ready to withdraw its forces from the valley, but Bakhshi didn’t second his thoughts.

Ishaq claimed that Bakhshi wanted New Delhi to deal Kashmir with an iron fist so as to keep his irregularities and loot safe from any criticism. Bakshi family was one of the richest in Kashmir during his rule.

Ishaq claimed that motive behind toppling Sheikh Abdullah and installing Baskhi was former’s realization that by merging with India he has made a mistake.

While addressing various public rallies Sheikh accepted that “Historians should write that I was misled and should not refer to me as a betrayer.”

Ishaq’s memoir offers insight into some of the most uncomfortable questions that still fascinate Kashmiris after half a century. It would be great if an English translation follows the recently released Urdu version to help present generation understand their history in a better way.