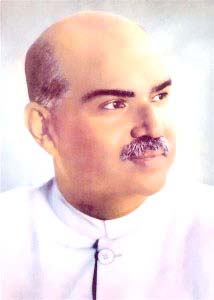

Founder of Jana Sangh Dr Syama Prasad Mookerji was the first fighter against Article 370. Historian Ashiq Hussain Bhat revisits the tumultuous 1952-53 to rediscover the man whose mysterious death in Srinagar had serious consequences for Article 370 and Sheikh Abdullah.

Dr Syama Prasad Mookerji died on June 23, 1953, while in the custody of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s government. His death furnished a much-awaited chance to Pandit Nehru to hit at his one-time protégé. Sheikh had bolted against Nehru Government’s ‘Policy of Gradual Assimilation’ of Kashmir into India. It was in April 1952 when Sheikh described as childish and lunatic Gopalaswami Ayyengar’s suggestion of extending the powers of Indian Supreme Court and Comptroller and Auditor General to Kashmir.

Ayyengar was then a ‘Kashmir expert’ because he had served Dogra Maharaja’s government as the Prime Minister.

Any extension of Delhi’s powers to Kashmir needed, under the provisions of Article 370 of Indian Constitution, the “concurrence” of Constituent Assembly of State. Article 370 had been drafted by Gopalaswami Ayyengar, in consultation with Sheikh Abdullah (see page 191 Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy by Alastair Lamb).

Article 370 was to be a temporary and transitional provision of Indian Constitution so that the relation of the State with Indian Union remained, for the time being, limited to the provisions of the Instrument of Accession, i.e., to the central subjects of Defence, Foreign Affairs and Communications, because it was thought that the time was not ripe for complete integration of the State because of the International Dispute as to the future of the State pending disposal in the UNO.

During Indian Constituent Assembly debates (1949-50) Ayyenger had made it clear in presence of Sheikh Abdullah and his partisans such as Afzal Beg, Moulana Mohammad Sayeed Masoodi, Girdari Lal Dogra, and Moti Ram Begra, that Article 370 was a temporary provision created to serve the purpose of assimilating Kashmir into India albeit gradually and with the “concurrence” of the Constituent Assembly of J&K (pp 524 Aatashi-Chinar by Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah). This Policy of Gradual Assimilation would be completed with the abrogation of Article 370 itself, but, again with the “concurrence” of the Constituent Assembly of the State.

The last clause of Article 370 reads: “The President may, by public notification, declare that this Article shall cease to be operative…provided that the recommendations of the Constituent Assembly of the State…referred to in clause (2) shall be necessary before the President issues such a notification.” When in 1949-50 the “Policy of Gradual Assimilation” was being laid down and Article 370 drafted Prime Minister Sheikh Abdullah did not raise any objection.

Contrary to common perception Article 370 was not promulgated to confer autonomy upon J&K. The State had been autonomous even during British times. It was autonomous even after accession. Although accession took away sovereignty and independence yet it conferred an autonomous status upon the State because accession was limited to central subjects of Defence, Foreign Affairs, and Communications. Article 370 was promulgated to erode that autonomy, gradually and with the “concurrence” of State Constituent Assembly that was initially presided over by Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah.

The spirit of Article 370 demanded that Sheikh Abdullah should obtain “concurrence” from the Constituent Assembly, which he headed, for assimilation of J&K into India (which included the abrogation of Article 370 itself) over a period of five years, the life-term of the State Constituent Assembly. However, by 1952 Sheikh had other thoughts because the process would progressively reduce his own authority.

It was this very reason that led Sheikh to react sharply to Ayyengar’s suggestions of extending powers of Supreme Court and CAG and thus became a persona non grata in the eyes of Nehru government. Instead of bowing down to Ayyengar’s (and by implication Nehru’s) diktat, he got resolutions passed by the State Constituent Assembly demanding a separate flag for the state; an end to dynastic rule; and appointment of an elected Sadri-Riyasat.

The Dogras of Jammu, who held ruling Dogra dynasty in high esteem and desired Kashmir’s complete merger with the Union, stood in opposition to a separate flag, a separate constitution, and a separate president. Under the banner of Praja Parishad (Peoples Party in Hindi), they launched a movement against Sheikh’s efforts to set up what they called a “Republic within Republic”. Ek desh mein do vidhan, do nishan, do pradhan, nahin challengay, was their dominant slogan which meant that they would not tolerate two constitutions, two flags, and two presidents in one country.

Led by Prem Nath Dogra and Sham Lal Sharma they organized public rallies and protest demonstrations demanding an end to the notion of “Republic within Republic”. Ending 1952 their movement reached its peak. Sheikh’s Government reacted with police action. Police used lathis and arrested Parishad activists and leaders.

Praja Parishad received overt support from rightwing Hindus in India plains, prominent among them was Dr Shyama Prasad Mookerji, the founder of Jana Sangh (Peoples Association). Dr Mookerji was part of Nehru’s Cabinet as Civil Supplies Minister up to April 1950 when he resigned and founded in 1951 Hindu right-wing organization, Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the precursor of modern Bharatiya Janata Party. He supported Praja Parishad’s demand for abrogation of Article 370. Also, he said that Kashmir should remain part of India whether its Muslim majority liked it or not. He maintained that the State Constituent Assembly did not represent the people of J&K. In the same breath, he demanded that this Constituent Assembly should pass a resolution to endorse accession.

During winters Jammu remained restive. In May 1953, Dr Mookerji set out for Jammu to take stock of the situation. Since he had no permit, which was required those days to enter into J&K, the J&K Police arrested him on May 11, 1953, at Lakhanpur frontier. He was driven to Srinagar and lodged in a bungalow in Nishat where a month later he died apparently because of a heart attack (pp.198 Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy). His supporters, however, suspected he was murdered. During Dr Mookerji’s incarceration, Prime Minister Nehru and Moulana Azad, a staunch supporter of Nehru’s Kashmir Policy, visited Srinagar and stayed at Chashmashahi, barely a mile away from where Dr Mookerji was held by Sheikh’s government. Neither of the two expressed a wish to meet him. Nor did they demand his release (pp. 559 Aatash-i-Chinar).

Dr Mookerji launched his battle against Article 370 from Kanpur, according to L K Advani with emphasis on complete integration. Prior to his entry into the state to defy the permit system, Mookerji and Atal Behari Vajpayee toured a lot of places to inform people about their campaign. Writing on his blog, Advani led a huge procession from Amritsar to Madhopur and crossed the bridge on a jeep. He was stopped midway and arrested for not carrying the permit. As he was arrested, he sent Vajpayee back to tell the people that he entered J&K without a permit albeit as a prisoner. Interestingly, Punjab police had called on him at Pathankot to convey that “they had instructions from the Punjab Government that even if Dr Mookerji did not have a permit with him he may be allowed to go past Madhopur on to the bridge.”

Advani says that Dr Mookerji’s death is “still a mystery”. In other similar situations, he wrote, a formal enquiry has almost invariably been instituted. But not in this case.

Regardless of the reasons for Dr Mookerji’s death, it made Nehru to withdraw his “protection” to Sheikh Abdullah and to remove him from the scene because Nehru feared for his life at the hands of Mookerji’s votaries (pp 563 Aatashi-Chinar). After Sheikh’s dismissal, Praja Parishad and right-wingers within and outside J&K cooled off. Even so, Sheikh’s incarceration, coupled with the international character of Kashmir dispute, delayed the “Policy of Gradual Assimilation” by a decade.

In 1963-64, New Delhi pursued the policy of assimilation vigorously. What remained of Article 370 thereafter was an empty shell, the nut having been eaten away by Delhi – this they did with the “concurrence” of state legislative assembly as State Constituent Assembly had concluded after doing its job.

Dr Mookerji’s death, however, “triggered off a series of developments in the next few months which significantly promoted the process of national integration,” Advani wrote on his blog.

The permit system was abolished. Authority of Supreme Court, Election Commission and CAG was extended to the state. Prime Minister of J&K became Chief Minister and Sadr-e-Riyasat became the governor. “In a way, of the three strands in the inspiring slogan, two pradhans became one, and though two nishans continue still, the National Tricolour started flying in the State in a superior position,” wrote Advani. “The country eagerly awaits the day when Art. 370 would be repealed, and the two vidhans also would become one.”

Now the question is whether Article 370 could be abrogated or not? If we go by the script Article 370 can never be abrogated because it would require the “concurrence” of State Constituent Assembly that ceased to exist since 1957. It was replaced by State Legislative Assembly. But if we go by the precedence of how powers of Lok Sabha were extended to Kashmir during the 1960s with the “concurrence” of the state assembly particularly those related to the extension of Articles 356 and 357 of Indian Constitution that empowered the President of India to dismiss State government, the sky is the limit!