After a long phase of unaccountability, Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Waqf Board (JKMWB) – previously the Muslim Auqaf Trust – is facing scrutiny. The premier body for the management of Kashmir’s Muslim shrines and donated assets worth hundreds of crores, had remained a no-zone for public accountability since its inception by the Muslim Conference in the 1930s.

For a larger part of its inception, it remained under the control of the National Conference. The religious institution with assets exceeding Rs 2000 crores has little to give to Muslims of valley in return, as a very small amount is spared for its philanthropic activists.

There are allegations that the Board has failed to use its resources for independent growth of Muslim talent and preservation of Muslim cultural heritage. Instead, for some time now, 60 per cent of income generated from donations at shrines and rent collected from shopkeepers is spent on the salaries of the employees whose numbers have swelled from 461 a few years ago to 1093. Another 35 per cent of the revenue goes for maintenance, renovation and construction of shrines and mosques leaving very little for the innumerable needs of the Muslim community in Kashmir.

“Of course, there is a scarcity of money to help the destitute in a sufficient way. We do render helping hand to a few but that is quite nominal as per the need and we wish to have more money spared for people in distress,” acknowledges M Y Qadri, Vice Chairman, Waqf Board. Interestingly, people in dire need are sometimes provided help from the interest money of fixed deposits. Secretary Waqf Board G M Rather says they are compelled to help the needy by interest money – prohibited in Islam. “Its alternative could have been Zakat which people do not contribute to Waqaf. We have a Zakat section and from this year we will go on collecting it to help destitute, whose number has shot up due to prevalent situation, in a better way.”

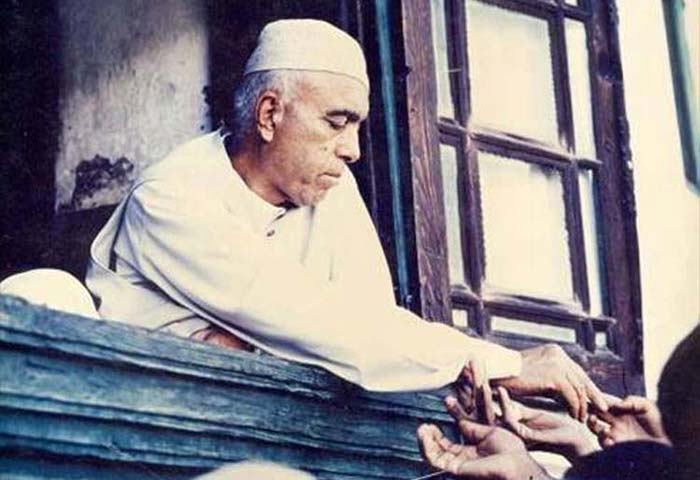

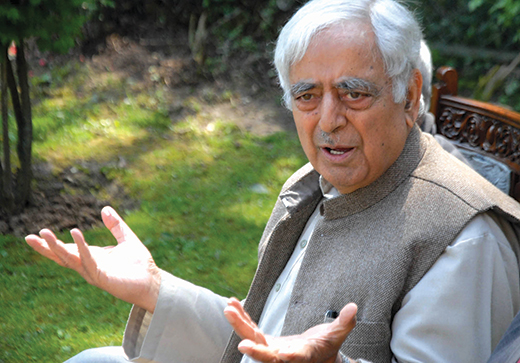

Social uplift was one of the motives when the Muslim Auqaf Trust was formed in 1930s by Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and his associates. “Muslim Auqaf had come into being as a part of the freedom struggle of Kashmir when Sheikh Sahab and his friends thought that institutions of faith (shrines) are generating a good income which should be spent on social, educational and other needs of the Muslim society,” says Nayeem Akhter, Chief Executive of Waqaf Board during Mufti Muhammad Sayeed’s regime.

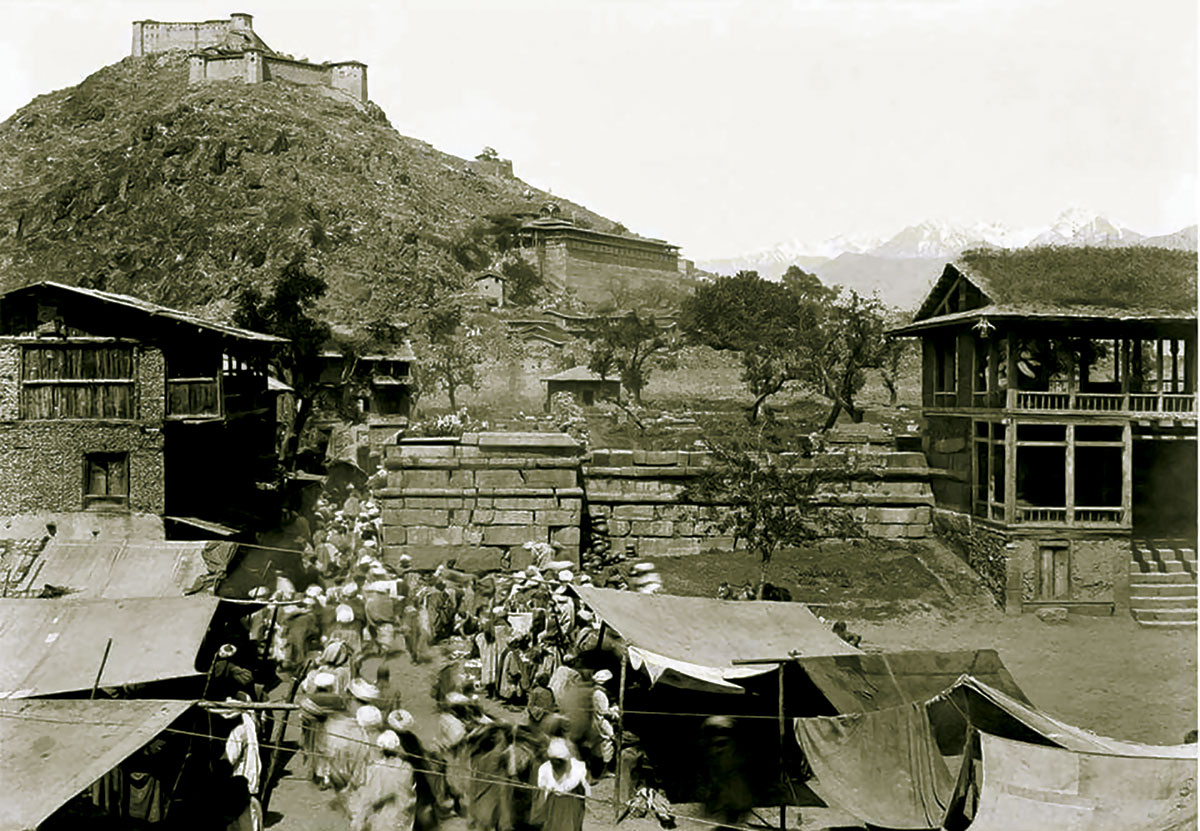

Over the years public interest in the affairs of Auqaf has declined as the populace knew pretty little about its functioning. The Auqaf virtually turned into a family estate. “National Conference, earlier Muslim Conference, were at the vanguard of freedom movement and many of NC demands centred around religious issues during Maharaja time. It is because of this that NC could liberate religious places like mosques and shrines from Dogras. After 1953, Sheikh Sahab tried to cultivate institutionalisation of Auqaf further and the fact remains that Auqaf became an institution primarily because of this party (NC),” says Dr. Gull Mohammad Wani, Associate Professor Political Science department, Kashmir University.

According to Akhter, “With Sheikh Sahab at the helm of affairs, a system had developed. Given his personality, his overwhelming influence, his acceptability and his popularity, nobody could question his heading it and his undoubted religious credentials in Sheikh Sahab’s lifetime.”

However, it was Sheikh’s stature that scuttled any grain of accountability from entering Auqaf premises, which later on lead to its stagnation. “NC had naturally a control over Auqaf and it got consolidated with the construction of Hazratbal shrine. NC’s political strength was generally perceived because of this – religion and politics getting together. So naturally, for some parties, disinvesting NC from it was a big headache,” says Dr Wani.

And once politics surrounded the sacred institution like Auqaf, politicians threw a vicious circle around it resulting in its degeneration. “When Sheikh Sahab’s government was pulled down and he was arrested, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad took over. He became its head. There was no legal framework guiding this. Any usurper could come and take it. Even a person like Bakshi who didn’t have any popular ratings as compared to Sheikh Sahab found it easy to get it. There was no mechanism either to appoint people or remove them or to hold them accountable,” says Akhter.

“And finally Mufti was able to get it out of the control of a particular political party and tried to institutionalise it and give it a new focus and orientation. To what extent Mufti was able to run it on autonomous lines and establish it on modern principles remains to be seen once the clouds clear over the facts of its functioning,” views Dr Wani.

Seeing the public faith witnessing enormous erosion in Waqf Board, the new establishment is trying to come up with a status paper to show a semblance of transparency from now on. However, on queries about its past record, the Board authorities are reserved.

The huge resource base has been misused over the years. Inferences can be drawn from the fact that for 1400 shops owned by it the Board generates half the revenue that Ziyarat Makhdoom Sahab generates per year. “The income from Makhdoom Sahab (shrine) is Rs 1.25 crores a year,” reveals G M Rather. It is double the total rent of around 67 Lakhs that 1400 shops owned by the Waqf Board generate every year.

The assets of the Board according to Qadri include hundreds of properties across the valley, 1400 shops, many complexes including Suleman complex Dalgate, Boulevard complex, Hazratbal complex, Taj Hotel Lal Chowk, Gulmarg Hotel and Municipal building. Besides, 89 shrines and 2100 kanals of orchard land associated with these shrines come under its purview.

“You will be astonished to know that the monthly rent of one of the Waqaf buildings at Karan Nagar with 58 rooms, three big halls and some parking space is a mere Rs 3500. The building is rented to Geology and Mining department since 1976 and the rent has not been paid since 2005,” says Qadri. “The rent-structure needs a total overhaul as shopkeepers at Lal Chowk who occupy Waqf shops pay a meagre Rs 200-300 a month and the rates at Dalgate have been fixed at Rs 400-700 a month. Even this nominal amount is not being paid in time and we have an outstanding of Rs 2.5 crores.”

However, Waqf’s Vice-chairman is confident that rent will be fixed afresh which will generate more revenue. Taking market rates into account, Board loses about Rs 4-5 crores annually on the rent component alone. The orchards scattered in the entire valley have been encroached by people and sometimes usurped for years.

The land grabbing case of a big apple orchard in Asham (Sonawari) in north Kashmir was a big jolt to the Board. The apple orchard with an area of 692.7 Kanals (86.5 hectares) had been contributed by a Kashmiri who migrated to Muzaffarabad in 1947. Till the onset of militancy, the Muslim Auqaf Trust was managing the entire orchard and its income was being used for Madeena-tul-Aloom, a Quranic school in Hazratbal. However, after the militancy started, it was grabbed by a top militant outfit. Later, it was shared by two other outfits and after that, a counter-insurgent outfit took possession of this orchard. The land was recovered after the death of a top counter insurgent.

Later, however, Auqaf Trust’s income witnessed a significant jump. Its income stood at Rs 7.68 Crores in 2000-01, Rs 8.54 Crores in 2001-02 and Rs 8.91 Crores in 2002-03. But the trust continued its tradition of showing most of its income going for maintenance of assets and repairs. Its expenses were at Rs 8.21 Crores in 2000-01, Rs 8.56 Crores in 2001-02 and Rs 7.36 Crores in 2002-03.

In 2003, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed’s government brought the trust under government control and transformed it into Muslim Waqf Board. In 2003-04, Waqf witnessed a surplus of Rs 1.9 crores and in 2004-05, the surplus was 1.42 crores. The decline in revenue started in 2005-06 when it registered a deficit of 3.94 crores. In 2006-07, the revenue and expenditure were almost equal and then in 2007-08 Board witnessed a deficit of one crore rupees. In 2008-09, the income was 11.21 crore and expenditure stood at 10.75 crores.

“As against sanctioned staff strength of 700 employees, there are 1093, most of whom have been recruited during past few years. Earlier the pay bill used to be 2.37 crores which has gone up to six crores. From 2006-07, fixed deposits have been regularly utilised to meet expenditure and cover the deficit,” informs Qadri. “There is, however, no evidence or record to show that approval of the Board of directors or the chairman has been sought in this regard.”

After its creation in 2003 through legislation, which put it under the direct control of the chief minister, the Waqf Board’s first CEO was a chief secretary-level officer who was given the minister of state status. However, compared to Waqf Board, the Shri Amarnath Shrine Board (SASB) is directly run by the Raj Bhawan and the governor uses his authority as its chairman. Its CEO forces the constitutional sanctity of the Raj Bhawan to exert pressure on the state government for implementing its requests.

A purely religious body Waqf Board has recently turned into a battlefield for the exhibition of political acrimony between the National Conference and Peoples Democratic Front. While the Muslims of the state are constantly facing myriad challenges at several fronts, pro-Indian politicians are vitiating a purely religious institution for their sheer political interests.

“The clamour of politicians over a Muslim religious body is deplorable. Who are they to bring dirty politics into a sacred Islamic institution like Waqaf while they did not dare to wink at Shri Amarnath Shrine Board and Mata Vaishno Devi Trust,” questions Abdul Majeed Shah, a Muslim cleric from Islamabad?

The expenditure incurred on wages and education has adversely affected the construction of shrines. “All I can say is that during the six years of Congress – PDP government, the work on the shrine almost came to a halt. None among the ministers visited the Ziyarat to see the progress on work or other needs here,” complains Manzoor Ahmad Jalali, Administrator Sheikh Noorudin Noorani’s shrine Chrar-e-Sharief. “Prior to and after PDP-Congress government, the pace of work has been satisfactory,” he adds.

Similar complaints are voiced from other parts of the valley. “We handed over Rs 50 Lakhs to the Board during past six years but got only 2.5 Lakhs in return for the renovation of the shrine,” complains Haji Bahaudin, a custodian of Kabamarg shrine that houses holy relics of Prophet Mohammad (SAW). Qadri says that Waqf indeed received this money but the same was “spent on other important things.”

“We visited the shrine and have consulted an expert to remove the defects in the mosque and shrine structures at Kabamarg on which the work will start soon,” he assures.

With many things on an anvil, it is to be seen whether the new establishment will succeed in evicting encroachers, fixing rent and premium and streamline administration. And above all, will someday a purely Muslim institution get rid of the political influence that is genuinely not allowed in the matters of other religions in the state.