The guerrilla group that Burhan Wani gave birth to is a completely different entity by way of evolution and operation. This generation has changed not only the counter-insurgent policy making but also the societal trends. But the more they defer with Kashmir militancy version 1.0, they eventually come so closer to their predecessors, a Kashmir Life report

Since the first blast ripping apart the Srinagar Club and the Central Telegraph Office on the last night of July 1988, Kashmir is now witnessing the second generation of militancy. This generation owes most of its genesis to the teenage rebel Burhan Wani. But the two phases of militancy separated by more than 25 years of Kashmir’s pain and pathos, despite being similar in avowed objective, are greatly dissimilar in systems and processes, operating in completely changed spaces.

There are striking similarities but the differences are sharp.

Virtual Militancy?

Burhan Wani, the teenage icon, whose killing in an encounter paralysed Kashmir for most of the summer, was not a great fighter. He was an impressive strategist, instead. He resurrected militancy and helped it evolve in such a way that it is on auto-pilot. Without moving much out of the south Kashmir forests, he create a cult-figure for himself, to the extent that Pakistani premier forgot all the top separatist leaders and talked about him in his speech to the UN General Assembly, last year.

Pushed to the jungles at a very early age, Wani evolved an identity for the new age militancy. It took him nearly half a decade to get his like-minded and weave a narrative of common cause and conviction and make militancy relevant to Kashmir at a time when the security grid was writing the obituary of turmoil.

Given the fact that Burhan resurrected the rebel in the backyard woods, the militants of 2017 are a different variant of their predecessors of 1990s.

The fundamental differences between the two generations of militants are quite interesting. A section of the youth in 1990s joined militancy because rebelling and the Kalashnikov became a new fashion statement. They would board a vehicle and reach some border belt and cross over. The militant of 1990’s operated in a weapon-abundant space. Compared to the counter-insurgency grid, his communication set up was much superior and fast. He would rely on media to communicate or, in rarest cases, go to the local communities and talk. He would make serious attempt to hide his identity and operate under aliases, sometimes more than one. He meant rebellion, had enough of weapons but lacked a clear guerrilla strategy. Hit and run was the basic routine. Often, for a recess they could cross over to LoC.

Though, the avowed objective is the same, Kashmir has changed in a different space since 1990. Most of the militants now are driven away to jungles by the revenge, where they discover conviction. They have not access to massive weaponry unlike their predecessors. Unlike 1990s, they take a lot of time in deciding to join militancy. A good section of new-age militants have come out of jails and then taken up the gun. Some have left the active service or a promising career which is slightly different from 1990s. Most of the militants are educated unlike 1990s when it was vice-versa.

The closure of the LoC has made a big difference. Unlike 1990s, LoC is well guarded and mostly fenced. Though it still is not impregnable, it has emerged as a major barrier in border crossing. They are low on training but high on delivery. They operate with real names and avoid hiding behind their aliases. They rarely keep their faces hooded.

What has made a major difference between the two generations of Kashmir rebels is that the new one has access to a huge IT platform and helps them in instant communication to a host of population. Using this tool, they emerge instantly in the public space. This has led many top cops to dub them virtual rebels. Interestingly, no militant belonging to Burhan era has ever issued a statement to the media. Their actions in real space and virtual world automatically become news, an advantage their predecessors lacked.

Death of Fear

The new age militancy has, however, changed the DNA of the society. If in 1990s, it was fear of death that would dictate the major shifts in an uncertain society; in 2017 it is death of fear that is forcing a policy shift. An estimated 20 youth were killed while trying to help militants escape. Now this has emerged a major crisis for the counter-insurgency grid. Usually, there are two battles taking place almost at every encounter site: one between militants and the army another between restive unarmed youth and the police. This has led to a series of controversies of the highest order.

Now all the counter-insurgency policies are being framed on basis of this major development: the death of fear. Various garrisons which have been withdrawn were revived in south Kashmir. The army in a series of operations have resumed the cordon and search operations (CASO) and in most of these operations, public marshalling of the younger lot is emerging a new effort to reassert the authority of the state. In many cases, the army and paramilitary usually resort to damage of homes and the properties too.

Striking Political Similarities

The mass participation in the March 23, 1987 assembly elections was the result of a series of historic events that had started reshaping Kashmir between April 4, 1979, and February 11, 1984. The two landmark dates had immense impact on the psyche of Kashmir.

After massive rioting, mostly permitted by the state apparatus in Kashmir, a huge section of the society that vandalised the properties of the Jamat-e-Islami members in reaction to the hanging of Zulfikar Ali Bhuttoo in April 1979, later got into self introspection. It led to new ‘awakening’ getting massive cadres to Jamat and to its then student wing, Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba, and then led by firebrand leaders like Ayub Thakur and Sheikh Tajam-ul-Islam. At one point of time, they said they stand for an Iranian sort of revolution in Kashmir.

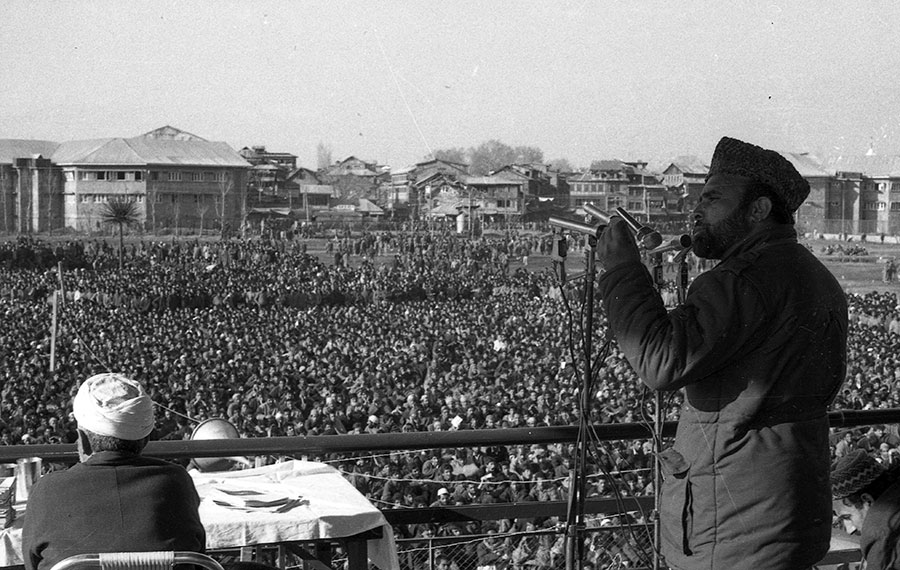

Photo in Special Arrangement with: Merajuddin

Much later when the state government signed the black warrants issued against Maqbool Butt, the JKLF co-founder, for his hanging in February 1984, the political forces outside the Islamist fold were compelled to rethink. Though a small minority of the angry youth started thinking of a violent response – a few actually availed the option of getting trained in handling arms and ammunition, the rise of Muslim United Front (MUF) offered a vibrant platform for the political dissent. The result oriented political movement, assimilated separatists of all hues, the Islamists and seculars. Even sections not believing in the ‘vote politics’ played a supporting role.

Participation in March 1987, elections created a new record: 79.10 percent. But the results were quite disarming. MUF got only five seats and ended runner up at 31 places The disillusionment created by the manufactured outcome, had a tragic follow-up: arresting some of the top MUF leaders, some directly from the vote counting halls; serious systematic efforts were launched for the disintegration of the MUF using deep sleepers within; and a headless platform failed to manage the support base, it had created. Its lawmakers were, by and large, consumed by the governance structure as they failed to articulate the crisis on ground. This created a gulf that was filled by militancy. It eventually led to the resignation of four of the five MUF lawmakers on August 30, 1989.

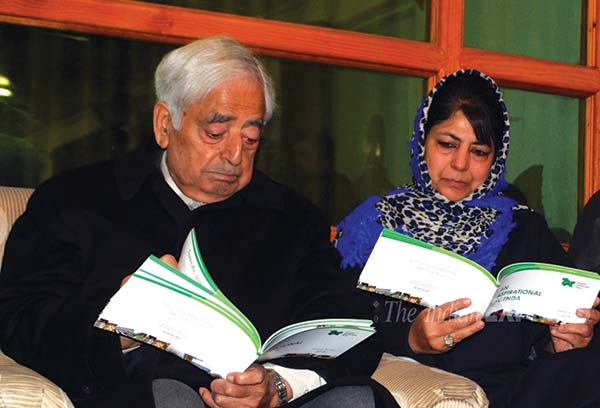

There are no comparisons. In 1999, Kashmir’s oldest Congressman Mufti Mohammad Sayeed foresaw a possibility in the wide gulf and a lot of middle ground created by militant-military collision on ground and a sort of insulated secretariat managed by the hugely mandated (numerically) National Conference (NC) government. Picking up a ragtag from the have-nots, getting greenery to its flag from the separatist camp and helping migrate the Qalam Dawaat (pen-inkpot) from decimated MUF to his newly created Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), the ground situation dictated the policy of the new party: the human rights, dialogue, development, jobs and responsive government. In 2002 polls, the father-daughter eventually succeeded in creating an alternative to Kashmir’s oldest political party. The three years rule continues to be the last reference in responsive governance.

As a flood decimated Kashmir was readying for new elections, Narendra Modi had given birth to a new India. A creative social engineering shocked India and when it came to J&K, rightwing force exhibited confidence that it can mange 44 seats in J&K House. Building on its record of earlier term, floods and the mess created by the 2010 unrest, the party offered checkmating BJP to retain the special position of the state with added emphasis on dialogue and raising the expectations. The response was phenomenal, the second record in Kashmir’s electoral politics. But the verdict sealed its flexibility. It ended up embracing the same force it said it will fight. Though the entire political space was not supportive of the PDP’s “fight”, the accord, albeit on basis of a shared understanding, did not prevent creation of political gulf. Though Mufti launched his government by thanking Pakistan and militants, to the serious disadvantage of Modi government, the sting was out once the administration set free Masarat Aalam and re-arrested him again.

“We used to get our polling agents to say us good bye,” one PDP leader said, “They said they are leaving the party and joining militancy.” There were various cases of neo-rebels migrating from unionist politics to jungles, taking up guns, and dying for the defiance. Even in 2014 unrest, there were quite a few instances involving the party cadres of both NC and PDP. The use and abuse of power in the 2014 unrest contributed immensely to the movement of defiance and continues to be. With generation net in command, PDP followed the NC with one major difference. Unrest 2010 helped PDP but 2014 could not help NC. On ground, Kashmir is witnessed reversal of political forces, from unionist camp to separatism.

A Stony Start

In a situation of political gulf, the ground exhibits strangely. Not known to this generation, 1988 looked almost as if it was 2017. Tensions erupted in the city within days after the government changed the power tariff. Though it barely touched the domestic consumers as it was mostly about industry, mostly concentrated in Jammu, the agitation was so ferocious that police cold not control the situation. In one day, alone, 17 youth fell to the bullets in massive stone pelting events. It, as later events suggested, was the outcome of the gradual shift of the political forces. Youth were so angry and restive that Mirwaiz Mohammad Farooq, whose Awami Action Committee, was part of the double-Farooq accord and had a couple of seats in the assembly, was keen to exhibit his indifference with the NC-Congress coalition led by Dr Farooq Abdullah. This part of the accord was grounded automatically with the rise of militancy, later.

The number of deaths and massive fire arm induced morbidity converted Kashmir into a strange unpredictable place. Flash mobs would assemble, resort to stone pelting and disappear in the narrow old cities alleys.

This situation led to massive police crackdowns across the city and its periphery. Youth started going under ground. Some of the boys arrested and tortured would take the first bus to Kupwara or Uri and cross over to the other side of Kashmir.

The police action against the stone pelters, now upgraded as trouble makers and over ground workers, now exhibits the modus operandi of 1990s. Newspapers published a couple pictures showing cops catching hold of a stone pelter and stripped them naked and parade them on streets. Though at a much later stage when the police crackdown had led to mass recruitment of the youth in militancy, police attempted taking the counselling line, but it was too late.

No Passive Reaction

Militancy marked its arrival by twin blasts in Srinagar Club and Central Telegraph Office during the last night of July, 1988. But the first assassination bid was made on the residence of Ali Mohammad Watali, then a DIG. Aijaz Dar, one of the first militants, was killed in the abortive assault carried out during the night of September 18, 1988. In the subsequent days, police arrested a number of militants and suspects. The volume of rebellion, the numerical strength of militants and the sophistication of their arsenal, gradually pushed police into the shell. As more and more CRPF personnel moved into the streets, they left dead bodies everywhere and it further added to the crisis that police was already in. In at least one case, during initial days of militancy, militants killed a police man in Kupwara and then prevented his funeral prayers forcing the family to hurriedly bury him.

The inertia in police reduced the huge force to mere scavenging and their only job remained registration of FIRs, collecting, identifying the dead bodies and despatching them. In countless incidents, the police were treated as harshly as civilian suspects, a chain of events which led to a cop’s murder by army, and the police agitation. Police would rarely accompany any other member agencies to their operations.

It took police almost five years and a lot of efforts at the managerial level to get them fight militancy. The creation of the Special Operations Group (SOG) in 1995 under the then IGP Kashmir Rajindra Tikoo was the outcome of these efforts.

The situation of police in 2017 is slightly different. While they are facing pressers at societal level, the police force has not given up its anti-insurgency activities. Unlike 1990s, when would play a secondary role to the armed forces and the BSF, in 2017 summer they are in the reverse of the leadership against rebels.

Kashmir police have, however, maintained one constant in its operations. In 1990s, they were accused of fording youth to militancy and the story remains unchanged in 2017.

In 1990s’, all the members of the counter-insurgency grid faced a strange cluelessness about militancy, especially the faces. Part of it was because of the decimation of the central intelligence network by them (read IB) and the fear factor that had set in within the police. This cluelessness was key to massive violations of human rights as soldiers wanted information that nobody had and then would accuse people of deliberately withholding it. Nearly 27 years later, counter-insurgency grid is more informed. Their operations this summer in which they are seeking rebels, rather than reacting to their actions, indicates an adequate intelligence flow, unlike 1990s.

Revisiting Unrest

Weeks ahead of Dr Farooq Abdllah government putting in its papers in protest against the appointment of Jagmohan Malhotra as the new governor of J&K, a mass unrest had emerged across Kashmir. People started thronging Srinagar streets for Azaadi. The only objective was to hand over memoranda to the United Nations Military Observers Group for India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP). This was happening at the peak of militancy. There were days when more than half a million were in Srinagar. This led to a series of massacres, initially in Gaw Kadal, a day after Jagmohan took over Srinagar Raj Bhawan, and later on March 1, at Zakura crossing and Tengpora in Batamaloo. It was only after the mass unrest was severely suppressed that the militancy started dominating the streets. There were small protests taking place within the Mohallas in urban spaces but no major protest was reported for decades.

KL IMage: Bilal Bahadur

There were some protests in Srinagar in 2006, quite small, over the sleaze racket and later in 2008 it was a full-fledged unrest, a situation that was repeated in 2010 and 2016. Interestingly, section of the youth who were in the forefront of these protests was arrested and some of them eventually joined militancy. The entire Burhan cadre was in a way, outcome of the 2010 unrest.

The only marked difference was that unlike the mass processions of 1990s’, the stone pelting remained the hallmark of a major number of protests in 2010 and 2016. The 1990s processions were as peaceful as they were in the initial days of 2010. They would face police with open chests and it led to a few photo shots which remained a symbol of Kashmir unrest for many years.

Diminishing Diplomacy

Burhan Wani’s name might have been mentioned by Nawaz Sharief in the state assembly and almost all the media houses across the globe might have had some sort of an obituary on him. But the fact is that Kashmir’s new age militancy lacked the diplomatic support that was around in 1990s. In fact, Americans were highly proactive on Kashmir for many years because they had strategic ties with Pakistan. By now, India and Pakistan has completely changed their allies. Now Russia is comparatively neutral, if not allied to Pakistan, as China and US, represent two powerful influences in the region.

But a major difference in the relationships between the separatist leadership and the militant brotherhood is gradually being redefined. When the Hurriyat Conference emerged in 1993, an unwritten principle was that every member in the executive should have some support of some militant outfit. Some organisations had to give birth to outfits to sustain their membership. That system collapsed soon as the survival of the fittest became the ground rule. Hurriyat survived sliced later, albeit for a different reasons.

Now at the peak of unrest, the separatist leaders have been getting cosy to each other. In2016, it has led to the emergence of a separatist triumvirate comprising Syed Ali Geelani, Mirwaiz Umer Farooq and Mohammad Yasin Malik. It is being now referred as resistance leadership.

While they continue to be undisputed leaders of this part of the ideological divide, they are facing momentary music from rebels too. While Zakir Musa left Hizb simply because he was publicly harsh against separatists, more recently, Syed Salahuddin, the PaK based UJC boss, issued a protest calendar. Though he withdrew it later, the message was conveyed.