by Majid Maqbool

In a seminal essay written as early as 1950, Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din urged writers to side with majority of people, not power, if they have to produce genuine art. “I feel a writer cannot go without politics but he cannot converge himself into the channel of party politics. A writer, if he is to give genuine art, must associate himself with the large majority of the people. Therein dwells the real life and real experience,” he wrote. Till his last breath, Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din, considered to be a trend-setter among the Kashmiri prose writers, would remain true to his words: ‘Courage Till Last’.

Returning a state honour like the Padmi Shri, especially in the turbulent Kashmir of 1990s, requires courage. To protest the hanging of Maqbool Bhat by the government of India, he returned his literary award, as he considered Maqbool Bhat as the “National hero of Kashmir”. And Maqbool Bhat’s hanging – by the same state that was awarded him the Padma Shri – was deeply painful for him as a Kashmiri. In his letter to the government of India and the Prime minister, he expressed how badly he felt about the hanging of Maqbool Bhat. And returning Padmi Shri was an exceptional – and courageous – refusal to accept a state award that was in fact given to him purely for the literary merit of his works.

Returning a state honour like the Padmi Shri, especially in the turbulent Kashmir of 1990s, requires courage. To protest the hanging of Maqbool Bhat by the government of India, he returned his literary award, as he considered Maqbool Bhat as the “National hero of Kashmir”. And Maqbool Bhat’s hanging – by the same state that was awarded him the Padma Shri – was deeply painful for him as a Kashmiri. In his letter to the government of India and the Prime minister, he expressed how badly he felt about the hanging of Maqbool Bhat. And returning Padmi Shri was an exceptional – and courageous – refusal to accept a state award that was in fact given to him purely for the literary merit of his works.Ghulam Nabi Khayal, a long time friend of Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din, considers this act as an exception that remains exemplary till date. “Up till now this award has been given to one dozen people from Kashmir but Akhter Mohi-ud-Din was the only exception, who returned the award and stood by his principles till the end,” says Khayal.

Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din’s son Azar Hilal recently compiled the last collection of Akthar Mohi-ud-din’s unpublished short stories. The collection was released at a function held recently in the cultural academy. He says his father repeatedly wrote to ministers in Delhi regarding the human rights excesses in the valley.

“When he saw that innocents were getting killed in Kashmir, he wrote to different ministers besides the home minister about the atrocities that security forces were committing in the valley in the 90s,” says Azar Hilal who runs a private educational institute in Lal Bazar. “He urged ministers to put a check on the excesses of security forces in Kashmir but when there was no response to his repeated pleas, he thought the only weapon in his hand was to return the award he got in the literary field. This was his way of showing solidarity with his people,” he adds.

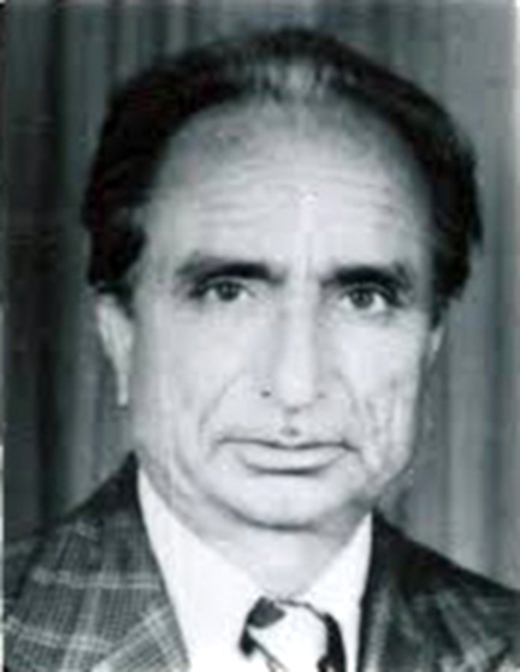

Born on April 17, 1928 in Batamallo locality of Srinagar, Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din wore many hats in his long, illustrious career spanning five decades: he was a government servant, Kashmiri writer, journalist, researcher, historian and a literary critic of repute. Author of an eclectic oeuvre that comprised of acclaimed works like Soenzal (short story collection), Dode Dug (novel), Zuv Te Zolana (novel), Tshay (radio drama), Gada Hanzany (Kashmiri translation of a novel from Tamil language), Akhter had tremendous command over, and knowledge of, Kashmiri language. He was the first Kashmiri who was awarded the Shahiti Academy Award for fiction in 1956.

Akther was one of the founder members of Progressive Writers’ Association in 1950s, which laid down the strong foundation of modern Kashmiri literature. “Akhtar Mohi-ud- Din was the best, the most outstanding short story writer Kashmir ever had,” says Khayal who knew him since 1950. “Akhtar wrote some 30 short stories, which makes it one short story after every two years. And his short stories reflected the real ethos and pathos of Kashmir.”

Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din’s novel Janamuk Panun Panun Naar, which he wrote in 1975, was published in 2003. He also wrote a travelogue salava mir, which is about his travels in Russia. Besides his original works of fiction, he translated Mohandas Karanchand Ghandi’s autobiography into Kashmiri. He also wrote the famous and critically acclaimed radio drama veth ruz pakaan.

Prof G R Malik, former head of the Kashmir University’s English Department says Akhtar Mohi-ud-Dind was a short story writer of world stature in literature. “The other dimension of his literary pursuits was that he was a very good critic of Kashmiri literature,” says Malik.

Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din’s acclaimed book on Kashmir history, which he wrote in English, A fresh approach to History of Kashmir, shed new light on the little-known aspects of Kashmir history. “It is a very important book in which he reviewed Kalhana’s Rajtarangini and other traditional sources of Kashmiri literature,” says Malik.

“It set many things right in Kashmir’s history and pointed to various sources which have not been attended to so far, like folk tales, folk songs, oral and verbal traditional storytelling and the excavations that have taken place in Kashmir,” says Malik.

Khayal remembers Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din as somebody would not stand the sight of any writer who wrote fiction to serve their personal interests. “He refuted the version of many non-Muslim historians about Kashmir history and corrected their distortion of Kashmir history,” he says.

Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din was a man of perfection – artistically skilful and had a tremendous command over Kashmiri literature. “Even if we read him today we will enjoy him like we did 50 years ago,” says Khayal.

Akthar painted the social aspects of life in Kashmir in true colours. And his characters have outlived him, become immortal. “Even today we don’t have any match to his perfection of artistic skill and maturity,” says Khayal. One of my beloved characters among my writings wrote Akhter Mohi-ud-Din in his essay, is Raaja of ‘Dode Dug’ whose soul, although she passes through heinous circumstances, remains pure and unstained. “She is impulsive and quick-tempered; she embodies much of my nature in hers,” writes Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din about his personality as reflected in his characters.

Mohi-ud-Din faced two big tragedies in his life but he never lost hope in the face of these tragedies. His son was killed by unknown gunmen and his son-in-law was killed by CRPF. From his personal tragedies, Akhtar Mohuddin emerged as a stronger person. “If somebody would talk to him about this tragedy, he would avoid talking about it and only say that it was God’s wish,” recalls Khayal.

Akhthar Mohi-ud-Din’s son Azar remembers how bravely his father faced the two tragedies that befell their family. “He was a man of iron will. He would never give up,” says Azar. “When my brother-in-law was killed by CRPF, he kept his three little daughters at home and was their guardian, and gave them protection. We still live together as a family following his instructions, as he desired that we should continue to live together as a family after his death.”

Akhtar Moudi-ud-Din’s relations and friends remember him as a sensitive person. “He was a very different, very sensitive person and a strict father at home,” recalls Azar. “He always maintained that distance between him and us, and lived a disciplinary life.”

“He was a very short tempered person in the sense that he would not stand any nuisance from anybody,” he says. “He would confront people and tell them whatever he felt about them on their face, but he would never indulge in backbiting,” says Khayal. “This was a quality in him.”

In his last years, Akthar Mohi-ud-Din suffered from intestinal malignancy. He died on 2nd May 2001. He was 74.