Within a year after her retirement, IAS officer Sonali Kumar came out with a book that seemingly attempts strengthening a narrative that has a strong popular dislike in Kashmir. But between the two covers is a rare subjective insight about how Babudom works in strife-ridden border state, reports, Masood Hussain

Batamaloo bus stand is 2 km from the civil secretariat in Srinagar and the Nedous Hotel is 4 km from the secretariat. Kashmiris do not know “what to do with walnuts, which in any case grew everywhere”. Most of Baramulla’s Hindu population “that could celebrate Diwali, was killed or chased away by Pakistan raiders in 1947”. One of the Chief Minister’s of Kashmir was Ghulam Shah. B R Kundal resigned and Chief Secretary and became a minister! And the reality that people kill the antelope for the animal’s precious fleece, the Shahtoosh was revealed in Ladakh!

“The Gandhi Nagar government colony was indeed constructed as temporary quarters for the Kashmiri employees coming for the winters to Jammu.

Presuming that the investment could be a waste if Kashmir ever joined Pakistan or Jammu became another state, the Kashmir centric government of the day had spent a little as Rs 8000 only on constructing those quarters.”

If a person offers these “facts” in a poorly written English book and the occasion is celebrated to be an addition to the huge scholarship on Kashmir, then the author’s 37 years of “service” in the state are genuinely “boring”. Even peons in civil secretariat know ‘Khaliq made DCs’ and not “Khalid DC”.

But Sonali Kumar, the IAS officer who superannuated last year, along with her husband, Arun Kumar, does not hide too much why she had to write her memoir Unmasking Kashmir: A Bureaucrat Reveals. The author has over-emphasised on her status of being an “outsider”, and the dislike she felt for “what I represented, which in my Sari and Bindi attire meant “Indianness”.”

“…Unlike any other state, in J&K, an “outsider’ or a “non-state subject” can not buy property, can’t educate her children in any technical, medical or engineering college, can not get her spouse or children to find employment with the state government, can neither vote in nor stand for any state level elections even after retirement, can not even get her son married to a local girl because that will immediately extinguish that girl’s state subject status, and so on,” the author writes in the chapter Why I Wrote This Book. This all is being attributed to a law “passed by the Maharaja of J&K in 1927 (20 years before India became independent and J&K acceded to India)…” The author asks: “How could I be an outsider in my own country?”

Apparently, the idea is to add to the narrative that rightwing parties have developed in last few years within and outside the courtrooms. It is demography in question and the quest for larger integration that is talked about. Since the devil has always lived in the detail, the “book” tackles the inter-babu tensions in a great detail. It talks about “the silent war” that most of IAS officers have to wage “against corruption and nepotism in a hostile state “cadre” that is imposed on them for the entire duration of their career.”

Kumar has tackled various babus but the stories are half-baked. Had she actually given the fuller details of what babus actually do in Kashmir, it could have been a huge thriller, the writing skills notwithstanding. The memoir has strong subjectivity.

After the two fell in love in the IAS Academy, the personnel department created a south-north of them. Arun came to Kashmir, the place he loved and Sonali to remote Kerala. The first exercise and a battle, the two fought was for changing her cadre. That experience, if one goes by the book, has left indelible impressions on the author’s mind. It was 1980, and Noor Mohammad was the Chief Secretary. He had allegedly created a situation at the policy-making level that squeezed the space for the IAS, hence the emergence of “outsider” that dominates this narrative.

“Mr Noor Mohammad was one of the most influential men in the whole of J&K,” the author writes. “In our little research, we had discovered that Mr Noor Mohammad had started his service as a junior stenographer in the legislative assembly (without coming through any transparent recruitment process). Later through his “connections”, he had managed to get promoted to the IAS with a funny seniority of 1956 and a half.”

Referring the then Chief Secretary as the “Jaffar in Alladin”, the author says the “evil sorcerer” was keeping the Sultan under his control by casting a spell. “He was short, fat and surprisingly as dark as a Bihari… like Arun, as I joked,” Sonali writes. “But he spoke English with a clipped non-Kashmir accent and floored us with his expansive mannerism welcoming us to J&K with open arms, literally.”

Sonali has written that Noor rose rapidly up the ladder “because of his cunningness and his ability to amass wealth”. When all India services were extended to J&K, Noor, according to the book became part of its “initial constitution” and was given the seniority of 1956 and a half. “He was from a humble background – his father was a village Chowkidar who in those days had to be paid by the villagers,” according to the book. “But when he retired, his assets in Mansbal and around were reported to be worth over Rs 200 crore.” Noor Mohammad passed away early this year after prolonged illness.

It was Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah; finally, whose intervention helped her change the cadre to J&K. The Chief Minister actually ensured that the couple stays together and they jointly operated from Baramulla, where, once “they dared to celebrate” Diwali! It was in north Kashmir town where they were formally introduced to Wazwaan and where Arun saw the first stone pelting with strong pro-Pakistan sloganeering.

It was again during their posting in Baramulla where they learnt that the people living close to the Line of Control (LoC) do marry their wards across the line and Baraats cross it with army facilitation. There, they also met Syed Ali Geelani, the MLA, who did not seem “obnoxious at all”, spoke in chaste Urdu with courtesy and civility, without realising how “this mild-mannered MLA would evolve into the great Syed Ali Shah Geelani, the pro Pakistan leader of the separatists, constantly spewing venom against India, the country he was still drawing his MLA’s pension from!”

After spending 37 years in J&K, Sonali says Geelani “changed his colours” after he started losing elections. “The change in strategy ensured that he could be in news even without being an MLA,” goes her hypothesis. “He could also then be a darling of the intelligence agencies from Pakistan as well as India and milk them both with equal felicity.”

Sheikh was highly accommodative and the couple were part of his funerals later. But Sonali says Kashmir’s towering leader had evolved a “syndicate” in his last day which was the top decision-making body and comprised the Chief Secretary, the State Police Chief and Secretaries of Planning, Finance and Forests. She said in too many words that he was surrounded by sycophants.

Sheikh was highly accommodative and the couple were part of his funerals later. But Sonali says Kashmir’s towering leader had evolved a “syndicate” in his last day which was the top decision-making body and comprised the Chief Secretary, the State Police Chief and Secretaries of Planning, Finance and Forests. She said in too many words that he was surrounded by sycophants.

The second officer Sonali has tackled is none other than Sheikh Ghulam Rasool, her first boss in the agriculture department, who gave her no work and put an IAS officer in a joint hall.

Rasool, she says, joined KAS through the back door without getting through any open entrance examination in 1964. Soon, he managed to get himself posted to the General Administration Department that looks after the service matters of all employees and thereafter remained in the department for 10 years. “Rising to the post of Secretary, the result was that he could not only get himself promoted to the IAS but could also fix his year of allotment as 1965!,” Sonali has written, terming him the new evil sorcerer. “So virtually after just one year of service in the local feeding service like the KAS he had been promoted to the IAS which was dubious as it may be an all India record! And now he was the Chief Secretary.”

It was Rasool, who disliked her for what I represented, which in my sari and Bindi attire meant “Indianess”. As Chief Secretary when a crisis emerged for she was ordered to report to her junior in an additional charge issue, she has written, Rasool threatened to open a case against her.

The book says that when she failed to get a decision in her favour, she decided to approach the Cabinet Secretary in Delhi. It was then that she learnt that Rasool was his friend because he was receiving “lavish gifts” from Srinagar.

“Apparently, the Cabinet Secretary was told that the beautiful shawls his wife had received were embroidered by the Chief Secretary’s mother, the exquisite Kashmiri silk carpets were woven by the latter’s sister, and the crates of apple were, of course from, Mr Rasool’s own family orchard,” the book reveals. “Funnily, even today when the senior Government of India officers receive such gifts from Kashmiri officers, they are told similar stories of how skilled the latter’s family members are.”

Finally, Sonali had the receptive ears in Adviser to Governor Mr S M Murshid. After he got approval to her file in a decision that had gone against Rasool, she briefed him about her Chief Secretary. “That he got his son appointed through the back door into JAKFED – a loss-making state govt organisation, and then scrumptiously into the KAS,” Sonali says she told the Adviser. “That he had given shelter to a DC of Anantnag district who was actually a BDO. This officer had put Rs 14 crore of Government of India money in his personal account and when caught, had absconded with his driver, personal security officer and official vehicle to hide in Mr Rasool’s official residence.” Besides, she had told the adviser that Rasool was thick with the anti-India and pro-Pakistan Hurriyat whose meetings were also being held in Mr Rasools official residence. Rasool put in his papers a year before his superannuation. He joined politics, become a nominated lawmaker and recently migrated from NC to PDP.

Sonali believes that only “pliable locals” were allowed to become Chief Secretaries. She believes that Mohammad Shafi Pandit, J&K first direct IAS officer, was shunted out and removed to Public Service Commission and pave way for Iqbal Khanday. Dr Farooq Abdullah and Khanday, Sonali says were friends but after Dr Abdullah resumed power in 1996, they broke, and the reasons for this break-up are being talked about in “hushed tones”.

Recapturing from another cancer, now, Sonali has written about his discomfort while serving Tamil Nadu’s Madurai, because of the practice of having Sambhar, a spicy lentil daal dish, served three times a day. “..But what troubled Iqbal most was the strict prohibition in force in Tamil Nadu and he told us at lengths he had to go, to get his daily booze on ‘medical grounds’,” the book reads.

I S Malhi and S S Beloria, are the only two IAS officers, who rose to the position of Chief Secretaries, who were specially mentioned by Sonali because they came from defence backgrounds and enjoyed the concession of not appearing in eight papers! She is especially angry with Malhi because he took very serious her son’s admission in St Stephens in Delhi. The Chief Secretary, he says, told her personally that he and his son could not make it to St Stephens College and “could only admire (it) from outside its gates”.

But she was impressed by Mehmood-ur-Rehman’s “run-ins with politicians (which) was legendary”. As Deputy Commissioner Leh, she reported, Rehman disconnected phone line of Gul Shah and restricted him to his room. Later, Sheikh tried to salvage the situation by inviting both to breakfast at his Srinagar residence.

Sonali, however, has decimated Mukhtar Kanth, her predecessor as Managing Director of Arts Emporium, a corporation. Terming him a “bull in a china shop”, she says he was appointed to the top position because of his relations with Chief Minister Gul Shah. “..He had created havoc to employees’ morale by suspending as many as 59 employees. In fact, the day I joined they had all gathered to beat up the then MD,” Sonali has written. She accuses Kanth of misusing a Rs 4 crore grant by the Government of India to “fill up all our showrooms with absolute junk. And I suppose filled up his own (and his masters) coffers well in the process.”

While studying the cases of the suspended employees, Sonali says they were reinstated because there was no case against any of them excepting that “they were aligned to the wrong political party.”

In describing the politicians, Sonali has remained guarded. In those days when the private sector was non-existent, the Indian Airlines as the lone carrier was the most influential one. Its Station Manager was very powerful and was operating from the government quarter which was too huge for his status. One day, Dr Farooq Abdullah ordered he be evicted. The manager, in reaction, put his response that the Chief Minister was fond of the pakodas, his wife makes. So when the eviction was about to happen, Chief Minister personally restrained.

Sonali said the Congress Deputy Chief Minister Mangat Ram Sharma had six sons who had nothing much to do. “So he allotted them different Heads of Departments and Public Sector Undertakings to deal with,” the book says, insisting they never came to her when she was Industries Secretary. But was transferred to Education where Shafi Uri curtailed her.

Suman Lata Baghat, Dr Abdullah’s Health Minister, told her that “why should two ladies fight?” when she refused to oblige her. Eventually, she came to her suggesting: “Why do not you have a setting with me then?”

But the most revealing thing, the author has credited to her husband. “I found it hard to believe when a prominent Muslim minister of Mufti’s cabinet showed Arun the Rudraksh chain (that only Hindus sport) he used to wear secretly under his short and admitted with some nostalgia that he was taught the Holy Quran by Kashmiri Pandit teacher in school,” the book reveals without identifying the politician. She insists that the land that triggered a row in 2008 after it was transferred to the Shrine Board was approved by the then Chief Minister Ghulam Nabi Azad, the then Deputy Chief Minister Muzaffar Hussain Beig and the Forests Minister Qazi Afzal.

The IAS officer, however, is very positive towards governors S K Sinha and Jagmohan. Arun served the two in three terms. It was Sinha who fulfilled her wish to fly to the Amarnath cave along with her son and husband.

In Jagmohan’s first term, Arun was given the charge of Director Information and he gave Raj Bhawan a positive press. On his recommendation, the book says the governor prevented Katibs (calligraphists) on rolls in Information Department to work for newspapers and also closed department’s centres in Delhi, Calcutta, Bombay and Jullundur. “He even allowed Arun to operate a secret fund, like intelligence agencies, with no questions asked,” Sonali reveals. Eventually, however, Kumar was once injured in a stone pelting incident outside his office as Director and injured. His car went up in flames. In his second term, the author says Jagmohan tried his best to “stem the tide”.

Some institutions have special mention, like the army. “If anything, they were not averse to selling their free rations including rum and kerosene, in the open market for a quick buck,” Sonali has written about her days in Ladakh. “Leh in those days had just one petrol pump for the entire district. But you could go to any village, and openly buy diesel and kerosene from the villagers at rates cheaper than the officially decreed ones, thanks to the ‘generosity’ of the army!”

The author even makes believe that bigwigs in the University of Kashmir were “getting funds from across the border”. She even claimed that experts from archaeology and museum departments were being hated “because they focussed on pre-Islamic period”. For personal reasons, she feels J&K’s Hospitality department is actually a hostility department.

For an officer who has spent a lifetime in Kashmir, why have the experiences been so unimpressive and bad? Perhaps one incident explains it a bit. When the couple lost some walnuts in Baramulla and found them stolen by rodents instead, they started consuming the fruit. It got Arun ill. Their first choice was the army doctor.

“Army doctor sent Arun to Dentist and prescribed some ointment to my “skin disease”,” Sonali writes. “Dentist concluded that Arun’s teeth were so sharp that they had hurt his tongue. So the remedy was to grind and blunt his teeth somewhat.”

As there was no change, the couple went to Dr Dar in the district hospital. As they explained the problem, Dr asked: “Have you had any walnuts recently?”

Seemingly, this is the net difference between what has been said in the book and what is left unsaid.

Shopping with Ms M

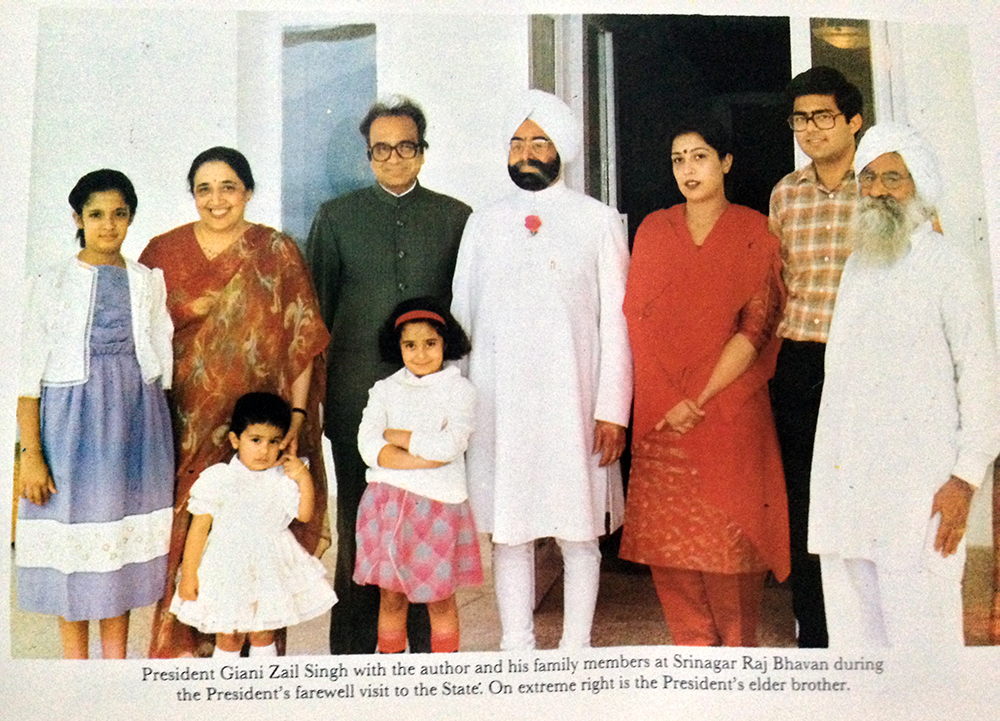

The Presidents of India had come to Srinagar along with his daughter. They were staying at the beautiful state Guesthouse in the Dachigam Wildlife Sanctuary, on the outskirts of Srinagar. Nothing unusual about that as Kashmir has always been a favourite holiday destination for the high and mighty in India. Hardly a year would pass when we would not have the President or Prime Minister (or both) in Kashmir driving the administration crazy.

Earlier while I was in Baramulla, I was put on duty to receive Mrs Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister, who was visiting some forward Army posts. Despite being just a year old in services, Mrs Gandhi had then floored me with her charm and kindness.

First, there was a sightseeing trip to the Mughal Gardens, which went off well thanks to the excellent arrangement made by the State Floriculture and hospitality & Protocol departments. The daughter, let us call her Ms M, was pleased and then expressed a wish to buy silk saris.

SO, I TOOK THE lady to the Raj Bagh Silk Factory which is a government undertaking and at that point produced the best silk chiffon saris in Kashmir. Ms M happily selected as many as 35 saris, each costing between a thousand to fifteen hundred rupees. I gasped as my salary at that point was about 1500 rupees per month. When it came to payment, Ms M declared imperiously that she was not carrying her purse. I looked at the ADC from the Navy who was accompanying her. He searched his various pockets and came out with about five hundred rupees.

The Manager of the factory who was also a government employee looked extremely perturbed. He looked at me, an ostensibly senior IAS officer of J&K cadre, silently imploring me to do something. So, I stepped in and gently told Ms M that since this was a government showroom we couldn’t take out anything without payment.

“I will get all the saris packed Mam and tomorrow when we move to the airport, we can pick it up after payment,” I offered in as polite a tone as I could manage.

Ms M did not look happy but couldn’t do much about it. Little did I know that this was only the light thunder before the proverbial deluge.

THE NEXT MORNING the Lady descended upon my Emporium. By now she had been joined by another sister and her family and they were all over the Arts Emporium lustily selecting Pashmina or Shahtoosh (which was not banned then) shawls, silk carpets, Papier mache – and what not. I could feel alarm bells ringing hard in my head.

So, I called aside the Manager of my showroom and told him to ensure that nothing left the showroom without payment! I next walked up to the ADC and asked him whether he had arranged for the money today in view of the heavy shopping that was going on. In his smart-alec way, the ADC remarked, “Mrs Kumar what will you do if we simply take all the stuff and walk out?”

My reaction was immediate.

“Look Lt. Commander (equivalent of Major in Army), I am the custodian of the artisans of Kashmir. And if you do anything like what you described, I would consider that a daylight robbery. I shall then go to the police station, which is just outside my Emporium gates, as you may have noticed, and register a case. Also as my husband has Information, I shall invite the press to first family of India does when they o J&K.”

The ADC looked at me in horror, “You can’t be serious!”

“Oh yes, I am and I’m crazy enough to do as I just said.”

Seeing the mad glint in my eyes, the ADC walked up to the Lady, and I saw her face turning a tomato red. Some phone calls were made and a local Sikh businessman turned up and paid for all that had been bought.

Ms M was so angry that she did not speak a word to me thereafter. In fact, she did not allow me to sit with her in her vehicle and escort her any further. So, we went to the airport) in separate vehicles. I was convinced that I was bidding my career goodbye.

At the airport, the two advisers to the Governor, Mr Qureshi and Mr Naresh Chandra were sitting along with the Chief Secretary, Mr B.K. Goswami. At the earliest opportunity, I narrated the whole incident to them in one breath and was ready to be reprimanded. But instead, they all burst out laughing.

One of them commented, “How right Mr Jagmohan was when he had said that Ms M is a nuisance wherever she goes. And had added that the only one who can handle her is Sonali. So why don’t we put her on duty with Ms M?”

Wish I had known!

To use an “outsider” to fix an “outsider”? How clever!

(Excerpted from Unmasking Kashmir: A Bureaucrat Reveals, a memoir by Sonali Kumar, a senior IAS officer, who retired last year. The book was published by Manas Publications).