Contemporary history lacks a clear analysis of the events that unfolded in Kashmir following ZA Bhutto’s execution. More than 35 years after Suhail A Shah revisits the mayhem of April 04 1979 to explain how it altered discourse and direction and changed Kashmir forever

The man was fleeing with a looted ‘hand stone-mill’ and when people asked him about the futility of the loot he replied, “The cleric told me, heavier the loot more will be the blessings from Allah!”

This almost clichéd story is the one you get to hear from anybody and everybody narrating the unfolding of that fateful day, 04th of April 1979, when the property of Jama’at-e-Islami (JeI) cadre were vandalized in the valley. One person killed, numerous injured, countless houses burnt down, schools set ablaze, libraries demolished and the Holy Qur’an desecrated; ironically, all in the name of Islam. The story of the man with the ‘hand stone-mill’ somehow carries the irony of the day.

A political ‘Annus Mirabilis’ of sorts, the year 1979 is regarded as one of the most instrumental years in shaping up the world order we are living in today, with events like the Soviet Union invading Afghanistan, Margaret Thatcher overturning an etiolated Labour government, return of Ayatollah Khomeni to Iran after 15 years in exile and the subsequent Iranian Revolution; unfolding one after another, cementing the foundation to a newer arguably more chaotic world order.

“The political experiments of 1979 continue to define our world,” writes Christian Caryl, an American journalist, in his 2013 publication, Strange Rebels.

Connected to these events or not, but by no stretch of the imagination an inconsequential one, another major event that unfolded in 1979 was the hanging of the ousted Prime Minister of Pakistan, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. An event about which an American journalist opined in his New York Times column, “The way they did it, he (Bhutto) is going to grow into a legend that will someday backfire” (NYT-Apr 05 1979).

Whether the ‘prophecy’ came true in Pakistan or not is sure a debatable issue but the day Bhutto was hanged passed off as a peaceful one in the region, with no major violence or upheaval being reported from anywhere.

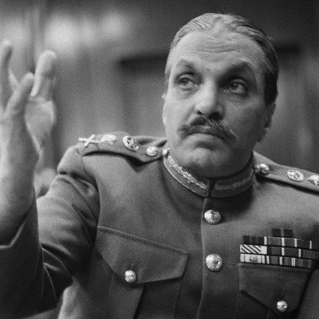

The hanging, however, did manage to create ripples, and of all the places, in Kashmir. While Bhutto was being prepared for his last journey, which led him to the gallows, at the Central Jail of Rawalpindi in Pakistan, Kashmir woke up to a sunny morning. The air pregnant with the fragrance of almond bloom carried the radio waves across Kashmir announcing the hanging of Bhutto by General Zia-ul-Haq led dictatorial regime. The rioting that day changed the political landscape of Kashmir forever.

But it was not the announcement of the hanging that wrecked havoc, recount the eyewitnesses; it was another announcement that followed this one.

“The Jama’at-e-Islami District Headquarter in Islamabad has been set ablaze by rioters,” 82-year-old Abdul Salam Kumar vividly remembers the words of the newsreader. Kumar, a government teacher and a Jama’at member, had already reached his place of work, by the time the rioting began, in a village adjoining his home village Redwini in what is now the Kulgam district.

The announcement, Kumar feels, led people into believing that Bhutto’s hanging was actually the handiwork of the Jama’at-e-Islami in Pakistan.

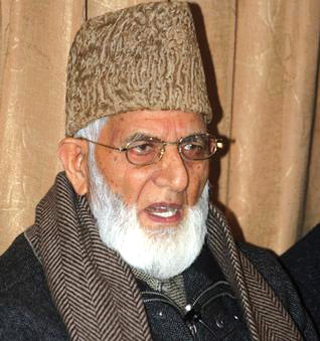

Besides, there had been a deep-rooted resentment against the Jama’at-e-Islami members and sympathisers within certain sections of Kashmir’s predominantly Muslim society, opines the Hurriyat Conference (g) Chairperson, Syed Ali Geelani. Geelani back then represented Jama’at in the State Legislative Assembly.

“Jama’at back then had made Islamic literature and the Islamic teachings accessible to the common people, through their schools and libraries,” says Geelani, “which obviously did not go well with the ‘secular’ minded people of Kashmir, who had been teaching people about religion and politics being two different entities.”

The only thing that Kumar witnessed throughout the day at his school was the smoke and wails emanating from his village, “I was growing restless to reach home but my colleagues held me back.”

Everybody was not lucky like Kumar. People were ‘fortunate’ enough to witness their houses and their granaries being gutted, their livestock charred and everything they owned taken away.

The violence was pan-Kashmir but the area that was hit the most was South Kashmir’s Islamabad district, which since then has been bifurcated into two, Islamabad and Kulgam districts.

The word of mouth says that things heated up in the Bijbehara area of Islamabad, where a religious cleric coined the slogan ‘Benazirai mainz kus laagi…moal hai morhai’ (Benazir (Bhutto), who will get you married now…your father has been murdered). Soon flared up passions got out of control and all hell broke loose.

In Bijbehara, the Jama’at-cadre-owned business establishments were the first to be targeted, “Ours was the lone shop that was left untouched after a neighbouring shopkeeper risked his life to save it,” recalls Advocate Iqbal Jan, whose father was an active member of the Jama’at.

After vandalising the property, the mob headed for the homes of the Jama’at members who by then had successfully went into hiding.

“Even that was held against us,” Jan says, “We had managed to take out some of our belongings and hide into a neighbour’s house. I heard the rioters pronounce us guilty just because we went into hiding.”

The family members of Ghulam Qadir Tak, who recently died a natural death, had also fled their house but left behind a sleeping newborn baby girl. The rioters, according to Jan, rolled her into the bedding and threw her out of the house. Miraculously, she escaped unhurt.

Of all the Jama’at members in Bijbehara, says Jan, two stood up and confronted the rioters, one Nisar Sanaullah, with a stick and another, Ghulam Muhammad Bader, with an axe, “The one with the axe was stabbed on his head with the same weapon and one with the stick escaped unhurt.”

Sanaullah, a lecturer by profession, was saved after the rioters turned out to be his students. Sanaullah, later during the turmoil of ’90s, disappeared from outside his house one evening and is yet to return.

The violence soon spilled over to other parts of South Kashmir as mobs, mobilized in Bijbehara, went on a rampage in the adjoining villages having a substantial number of Jama’at households.

Arwini, a village located a few kilometres West of Bijbehara town, has historically been a Jama’at stronghold and the next logical target of the rioters was this village.

A 70-year-old journalist, Abdul Salam Malik, from the village says that the village remained untouched on the first day of rioting, “people burnt down the bridge that connected the village to Bijbehara in order to stop rioters from crossing over.”

He said that the then-District Development Commissioner (DDC), Anantnag, Late Umar Jan visited the village during the intervening night of April 4, and April 5, and assured people that no matter what, no rioting will be allowed in the village.

“Police was deployed in the village, following Jan’s visit,” said Malik. The night passed peacefully for Arwini but in the morning mobs came marching in from Yaripora on one side and Zainapora on the other.

Before the rioters could reach the village the policemen deployed there vanished in thin air, recounts Malik’s 65-year-old wife Sara.

“A couple of policemen were standing guard outside our neighbour’s house and asked me to provide them some tea,” says Sara, “while I prepared the tea, the cops just vanished.”

Malik has never been a member of the Jama’at but his house was burnt down and so were many other houses which did not belong to the members of Jama’at, “The rioters had thrown away the rice we had cooked and in the evening I collected all of it in a cloth and fed my children,” says Sara.

Malik’s neighbour and a Jamaat sympathiser, 72-year-old Wali Muhammad is unable to hold his tears back while recounting the events of the day. A tailor and a manager at the Marketing Society of Kashmir back then, Wali Muhammad, lost everything that belonged to him.

“The rioters did not even spare the animals. My cow had delivered a calf a couple of days back and they threw the calf into the river,” recounts Wali Muhammad, who strangely breaks down into tears at the mention of his cow and its newborn.

Amid sobs, Wali Muhammad narrates that the cow jumped after its newborn into the river, “It always reminds me of what we humans need to learn from animals.”

Most of the Jama’at members and sympathisers in the Arwini village were hiding at a plantation nearby and came out only after everything was looted.

Twenty-nine-year old Abdul Rahim Sangkar, son of Muhammad Jabbar Sangkar was not among the lucky ones. He according to the locals was trapped inside his house when the arsonists came and the next thing people can remember is that he was found dead.

“Some say gunshots were heard from the house and some say he was stabbed to death,” says Malik, “But nobody knew the actual cause of his death.”

The arson and loot continued for three days and spilled over to every Jama’at household in Kashmir particularly the Islamabad district. The rioters cut down many apple orchards, including the one belonging to an ex-MLA from Buchru village, Abdul Razzak Mir.

“The then Chief Minister, Shiekh Abdullah, visited our house after the loot to express his sympathies,” recalls Sajad Ahmad Mir, 46, Mir’s nephew.

Mir was later killed by Ikhwanis (state government-sponsored civilian militia) on November 22, 1995, in Larnoo of Kulgam.

Sajad says that he was very young back then but clearly remembers that Sheikh asked for a chair to sit on and got a curt reply from Mir for being insensitive, “How can you ask for a chair, don’t you see everything has been burnt down,” Sajad quotes Mir as replying to Sheikh.

The property destroyed was estimated at nearly Rupees 40 Crore with 1245 residential houses set ablaze, 466 of them looted, 513 granaries burnt, 338 shops gutted, 70 apple orchards destroyed, 509 cow sheds blazed down and 24 Jama’at offices destroyed. (Source: Tehreek-e-Islami, Volume-2, by Ashiq Kashmiri).

Besides, 45 Jama’at run schools, 683 libraries and 10 mosques were also destroyed during the arson.

“The desecration of the Holy Qur’an and the destruction of Islamic literature hurt us the most,” says Sheikh Ghulam Hassan, 78, who has been associated with the Jama’at since 1968.

Faheem Muhammad Ramzan, in his early fifties, says that he witnessed the desecration of the Holy Qur’an in Qaimoh area of Islamabad district.

“I was a class 9th student then. I witnessed people tearing apart a copy of Qur’an calling it a ‘Maududi Quran’,” recalls Ramzan, “I was not from a Jama’at background but that incident deeply etched in my mind forced me to look deeper into the organisation.”

Copies of the Tafheemul Quran – interpretation of holy verses by Syed Abul Ala Maududi – were desecrated in every nook and corner of the valley, “some miscreants even left copies of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital in place of desecrated copies of the Qur’an.” says Malik.

The desecration of Qur’an in the name of Islam might sound bizarre but then it had snowed in the Sahara desert that year.

Shah Abbas, a senior journalist, recounts how the personal library of Maulana Muhammad Amin Shopiani was set ablaze, “more than a couple of thousand books were gutted in the fire.”

Spontaneous?

While some people may argue that the rioting was a spontaneous one and the people involved acted upon their overflowing passions, some people like to differ. The general perception among the Jama’at cadre is that the rioting was well orchestrated at least in 70 per cent of the places.

“We were smelling something brewing against us and that is the reason that Maulana Ahrar Sahab and me, days before the rioting, visited the then DC Islamabad Umar Jan and cautioned him of the conspiracies being hatched against Jamaat,” said Sheikh Muhammad Hassan.

On the 3rd of April, says Sheikh, he and the ex-MLA Mir visited the Divisional Commissioner in Srinagar.

“Despite the pre-emptive measures we took, nothing was done by the administration,” says Sheikh.

Historian and senior journalist, Zaheer-ud-din, believes that the arson and loot was not totally spontaneous, “The seeds were sown well before 1979.”

Zaheer-ud-din believes that a ban on Jama’at run schools in 1975 was a part of this political tussle Jama’at was involved in.

Geelani believes that Jama’at was growing into a political force to reckon with and the so-called ‘secular’ forces in Kashmir feared its rising popularity.

“The Shiekh Abdullah led government was equally responsible for the carnage,” Geelani says.

Government response and police inaction:

The victims believe that the government did nothing to take control of the situation and had there been a timely intervention from the police and the administration things would have not taken such a violent turn.

Petty political interests kept the state government from taking any measures either before the riots or after. (Source: Waadi-e-Pur-Khaar, by Qari Saifuddin). Qari further writes in his book that the then Chief Minister, Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah, was made aware of the situation by Geelani in the ongoing session of the Legislative Assembly in Jammu.

“The CM was made aware that Christians and Ahmadiyyas were also being targeted by the unruly mobs, along with the Jama’at cadre and the sympathisers,” writes Qari, “Geelani impressed upon the CM to visit Kashmir as soon as possible; however, he delayed his visit to the time when riots had completely gone off hand.”

Qari maintains that he was very disappointed with the then IGP, Kashmir, who had assured them of immediate action but his assurances proved out to be mere utterances.

The Jama’at members still feel that the government became a partner in crime for not acting in the way they should have.

The Jamaat response and the political implications:

Not much has been written or documented about the incident and the after-effects of it, but the oral history suggests that the response by Jama’at had been very dignified to say the least.

Jama’at members suggest that the then Jama’at Advisory Council headed by the Chief, Maulana Saaduddin Tarbali, announced a general amnesty for the rioters and withdrawal of all FIR’s against them.

“I was a college student and I clearly remember the announcement of the general amnesty at a Jama’at convention,” says Dr Hameed Fayaz, present Secretary-General of Jama’at-e-Islami Kashmir.

Following the riots the Jama’at cadre, while rebuilding their own shattered lives, also helped the people, without any affiliation to Jama’at, who had been caught into the arson, the social observers say.

The magnanimity shown by the Jama’at took some time to sink in and when it did the general perception, among some sections of the society, of the Jama’at being anti-Islam started to change drastically.

“When my house was gutted during an encounter in the ’90s, the same people who looted Jama’at households went out of their way to rebuild my house,” Kumar says, “I have come to the conclusion that these people were misled into believing that Jama’ati’s were a threat to Islam.”

The change of heart towards the Jama’at was instrumental in shaping up the political landscape of Kashmir. A senior journalist comments, “Jama’at would have had a sizeable stake in the 1987 elections, which the rigging ensured did not happen.”

The overwhelming pro-Jama’at sentiment that kept growing after 1979 had a major role to play in the quantum of armed struggle Kashmir witnessed, says the journalist. Rest is history.