Apart from affecting livelihood of nearly a million families and destroying crops and infrastructure worth billions, the September 2014 floods snatched Kashmir of its most popular raw snack, the Pambach. Shakir Mir tries to understand the Lotus disappearance from Dal lake coinciding with BJP’s ascend to power in J&K

Growers in and around Dal Lake, apprehend there will be no Pambach (Lotus Seed Pods) for next two decades, as September 2014 floods changed the ecology of the lake completely. In fact, the Lotus itself is battling for the survival.

Growers in and around Dal Lake, apprehend there will be no Pambach (Lotus Seed Pods) for next two decades, as September 2014 floods changed the ecology of the lake completely. In fact, the Lotus itself is battling for the survival.

Lotus’s great vanishing act, incidentally coinciding with BJPs ascend to power (Lotus is its party symbol), has impacted seriously the livelihood of thousands of farmers. Far away from the floating gardens, it has affected the taste-buds of many Nadru-eaters, now relying on Wullar and Mansabal produce.

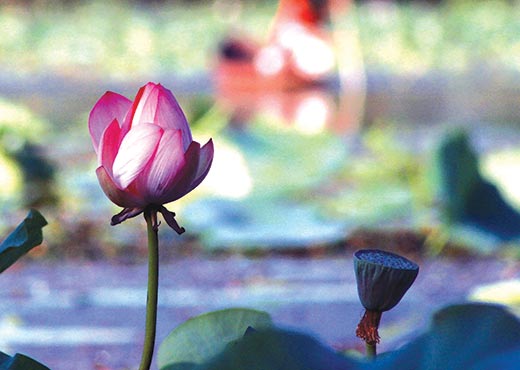

While the stem of the Lotus plant in Kashmir’s famed vegetable, its stigma is the Pambach.

Harvested on the onset of autumn, Pambach pods are sold mostly by vegetable vendors. Two-four pods bunch strung together cost Rs 40-50. A pod is basically a leftover stigma of a Lotus flower which grows – enclosing a colony of edible seeds, when the petals fall off.

“It has perished,” says, Ali Mohammad Sofi, a Nadru grower in Nandpora, a Dal backwater, where Lotus production has been the mainstay of household economy for ages.

Nandpora is marshy neighborhood located on the periphery of the lake and runs alongside Rainawari and Saida Kadal. Most of Nardu production in Srinagar comes precisely from this area where the prized water crop is grown on almost 10,000 kanals of private land along Dal Lake.

Until last year, growers extracted bundles of Nadru and Pambach for the floating market, another Dal pecularity. There are no motorable roads in Nandpora. Just few kms away from the heart of Srinagar city, most residents still commute through make-shift rickety wood bridges which link a warren of small disconnected tracts of landmass.

Pambach fruit recorded brisk sales until few years ago across the city. The pod is normally torn open and edible seeds are gouged out which consumers, mostly children, relish eating.

“I used to get it from a local vegetable vendor every day for my children,” says a retired school teacher from Old city. “But now, I don’t know why they are not visible anywhere.”

The gradual fading away of Pambach, however, is linked to a wider scenario involving a tragic demise of Lotus plant itself. Reason is more than one.

Last year when floods struck Kashmir valley, the isolated residents of Nandpora were among the first to drown. Sadly, the catastrophe coincided with the time when production from Lotus plants readied for harvest. “Gushing waters submerged the plantations,” says 50-year-old Ghulam Hussain Wani, a Nadru grower from Tankhan Bridge.

In face of rising water, the residents fled. Few days later, when the flood level started to recede, they trickled back to the marsh where water-soaked homes awaited them. Gradually, they began picking up the threads. But little did they know that a problem of enormous scale was around the corner. The following year, residents waited in vain for the Lotuses to bloom. For obvious reasons, they didn’t.

Flood waters had risen furiously, submerging the Lotus plantations and killing them. A Lotus plant, experts say, remains tied to its Rhizome by a long slender shoot and was therefore unable to catch up with swift water level rise. “Which is why it drowned,” an expert says. A Rhizome of Lotus is a subterranean part (below the soil) of its stem from which many edible arms shoot out.

Realizing that their livelihood was almost dissipated, the residents started scouting for other means. For instance the 70-year-old Ali Sofi, a seasoned Lotus grower from Ching mohalla was forced to row boat in Dal earning a meager Rs 400 a day. Zubair Ali, 20 from the same neighborhood started working as rag-picker.

In absence of any means to scrape out a living, many residents nibbled away at the aid that government had provided for restoration of homes. Thus homes of people like 55-year-old Mohammad Shafi are still in ruins.

Making matters worse is the large-scale presence of free-floating weeds, which, growers say, has inhibited the growth of Lotus plant.

Weeds like Watermoss, Azolla and Duckweed flourishes rapidly in water bodies replete with nutrients. The proliferating weed creeps across the surface thus blocking the sunlight from reaching the plants living under water which ultimately die or fail to grow and reproduce, say experts.

Traditionally, the growers demarcate their area of cultivation and place the dried Reed grass along the inlets where the water generally comes from. “The grass prevents the entry of free-floating weeds but let in the pure water,” says 30-year-old Mohammad Yusuf Chinga. “The remnant weed present inside is removed manually through sieves.”

But the turbulent waters of September 2014 floods simply overran the Reed barriers, allowing tons of weed to settle. Now the marshes of Nandpora are ridden with eutrophication. Some of marshes have been colonized by the noxious Hornwort weed (Ceratothylum demersum) which experts say, is detrimental to the aquatic biology.

Another culprit responsible for pushing Lotus to death throes is its very distant cousin: White water lily. Locally termed as Bum, water lilies possess disc like leaves which eclipse the water surface and thwarts the growth of Lotus plants in the same way as Duckweed does. In parts of city, Bum is a vegetable too.

“Basically, Water lilies have a life span much quicker than Lotuses,” explains OP Sharma, Director Ecology and Remote Sensing J&K. “They are capable of outgrowing Lotuses and consequently act as a ‘chocking agents’ and prevent plants under water to photosynthesize.”

According to locals, the inaction by the authorities is one the key reasons for the disproportionate growth of water lily in the marshes. “Every year LAWDA’s coffers are filled with crores of rupees to remove the weeds from our water bodies,” says one resident who did not wished to be named. “But they only undertake cosmetic measures. It is a common sight to see tons of weed accumulation removed on Dal Lake along Boulevard Road but in the outposts such as ours, the weed removal happens occasionally.”

Despite many attempts, LAWDA officials could not be reached for the comment.

Besides inefficacious Lotus yield, the costs of the ecological mismanagement are weighing upon heavily on the human life in marshes such as Nandpora. Few months ago, 70-year-old Ghulam Asghar Akhoon of Akhoon mohalla died of heart attack. Similarly, Mohammad Shafi Latoo of Kani Khech neighborhood was subsumed by mental depression before passing away. Locals say both these men couldn’t come to terms with the loss that untimely departure of Lotus had dealt to their busy lives.

But officials who Kashmir Life spoke to cautioned against the “impression” that Lotus was facing demise. “It is too early to say that it has actually happened,” says Sharma. “We have no conclusive evidence to suggest that Rhizomes have been uprooted.”

Sharma believes that it would take a year or so for Lotuses to survive the onslaught that floods had dealt to them. “We might hopefully see them again after one or two years,” he says.

Experts too, share a similar opinion. “Plants are highly evolved to withstand the vagaries of weather,” says Dr Zaffar A Reshi, a Botanist at University of Kashmir, while dismissing the possibility that Lotus would vanish. “It may not grow for one or two years, but ultimately it would.”

Prof Reshi says that plants such as Lotus have a breathtaking survival mechanism by dint of which they mobilize and re-mobilize the resources to withstand the anaerobic (sans oxygen) conditions. “Bio-resources necessary for the survival of plants oscillate between its roots and to leaves to provide nourishment accordingly,” Prof Reshi says.

Prof Reshi says that plants such as Lotus have a breathtaking survival mechanism by dint of which they mobilize and re-mobilize the resources to withstand the anaerobic (sans oxygen) conditions. “Bio-resources necessary for the survival of plants oscillate between its roots and to leaves to provide nourishment accordingly,” Prof Reshi says.

“Lotus plants submerged precisely when the resources had been mobilized from root to leaves and flowers. When the water level rose, it inundated the plants and killed them before the resources could have been sent back to the roots or Rhizome in the case of Lotus. Thus, the Rhizome lacked the sufficient resources to revive itself this year.”

Locals, however, sound despaired, out of any hope that it will grow again, at least for the next decade or so unless any intervention is made.

“A Lotus pant is capable to grow if a full stem along with its bushy end is buried deep into the soil,” a local grower explains. “But since no autonomous stem is left, we are not able to revive it.”

Locals say that they had approached the Lotus-cultivators in North Kashmir, seeking the full stem necessary to re-grow Lotus in Dal. “But they refused,” one local says, seething with anger. The refusal has material reason. “It’s pure economics,” an elderly person explains with a smile.

Apparently, North Kashmir growers are selling a bundle of Nadru at price as lucrative as Rs 250. The price has shot up in face of the dearth that non-productive Dal Lake has given rise to. “We used to sell a bundle between Rs 80-150,” another grower confides.

Locals allege that Nadru growers from North deliberately sell truncated stems so that they are no more utilized for cultivation. “They know if we start to grow Lotus again, the demand-supply relation will lead to fall of the Lotus price,” he says. “Besides, our Lotuses are more in demand than theirs.”

Prof Reshi, however, speculates that while the locals could grow the plants by seeds as well, they deliberately aren’t because of economic considerations. “They (locals) are not concerned with whether or not the Lotus will grow, they are concerned about the economic size of Nadru,” he says. “It will take many years for Lotus to produce Nadru of economical size if grown on seeds but then, who will buy a small slender Nadru?”

Meanwhile, Mohammad Subhan, a vegetable vendor in the Old City is one of the few persons exuding hope that he would sell Pambach again. “It has not gone,” he says. “It is just lying dormant. It will wait for the right time to come out.”