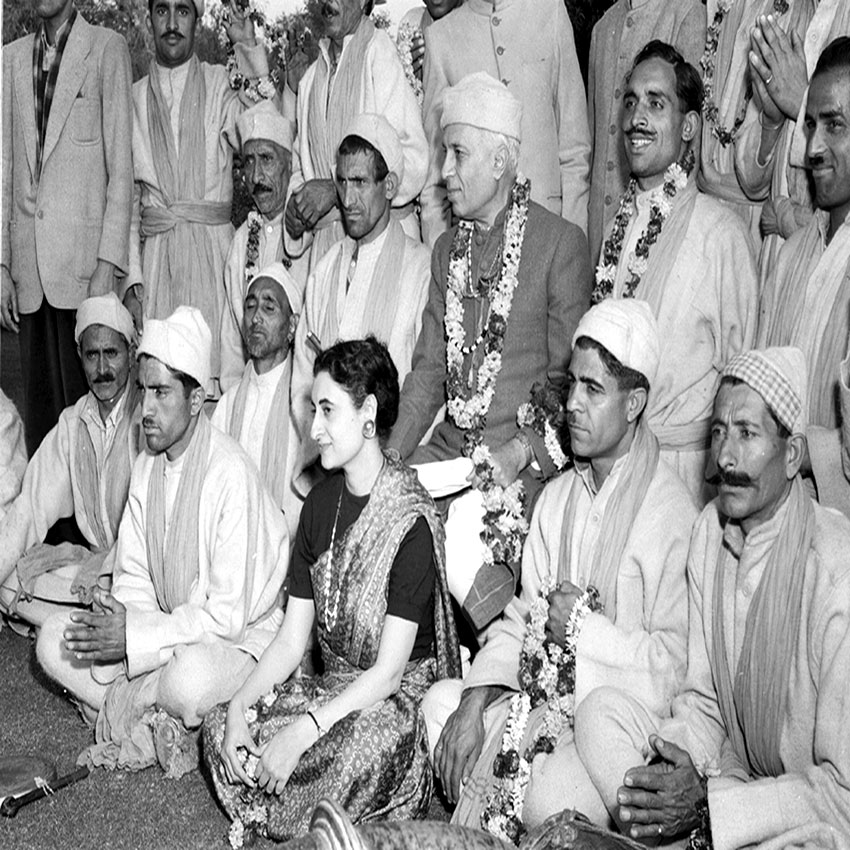

Scholar Congressman Jairam Ramesh is one of the few Indian politicians who have retained that Nehru style of politics, never give up writing. In his latest book Indira Gandhi: A Life In Nature, published by Simon & Schuster, Jairam has discovered the environmentalist in a Prime Minister who was known for her hard decision-making. The book by India’s former environment minister offers rare details about Indira’s Kashmir connections.

It was the night of 26 October 1984. Five days later she was to be brutally gunned down by her own security guards.

But that was later. For now, she wanted to fulfil a life’s ambition—and said so.

For almost half a century, she had been going to the land of her ancestors—a land she loved as nature’s paradise. It came with mountains, flowers, gardens, streams and, most of all, trees—particularly Chinars that over autumn explode into a spray of colours—from a deep vermilion to tones of burnt sienna to pale amber.

Off she went early the next morning, accompanied by her grandchildren, to see the Chinar trees in all their glory.

She had never seen this gorgeous sight and, after years of putting it off, she desperately wanted to experience it first-hand. The governor of the state advised her against visiting because of the prevailing political situation. But she ignored what he had to say.

Off she went early the next morning, accompanied by her grandchildren, to see the Chinar trees in all their glory. She also visited her favourite Dachigam National Park—literally walking on a carpet of leaves. A strange sense of satisfaction engulfed her.

She came back to Delhi on 28 October and wrote a foreword for a book authored by a ministerial colleague. It happened to be a book on her abiding love—the environment. She then left for Orissa the next morning. On the 30th, she made her very last speech in Bhubaneswar in which, famously, she seemed to have a premonition of a violent ending to her life soon.

Her premonition turned out to be right. The very next morning at around 9 a.m. she was walking briskly from her home to her adjoining office to record an interview for the BBC. Within a few minutes, however, she was assassinated in a most ghastly manner, at point-blank range, by two men assigned to protect her.

May and June 1934 found Indira in Kashmir with her mother. This was her very first visit to her ancestral land, and on 11 June she wrote to her father from Srinagar:

“In this wonderful land, no matter where you are you get a lovely view of the snow-covered peaks which surround it and the beautiful springs. I don’t think the waters of Kashmir can be compared to those of any other country. They have a standard of their own […]

Ever since I first saw the Chenar [sic], I have been lost in admiration.

It is a magnificent tree.”

Indira’s admiration for Chinar trees would only grow with time, and as I described earlier she was to soak in their beauty mere days before she was gunned down.

Kashmir continued to hold a special fascination for her—as it did for her father—and, I believe, was crucial to her evolution as a naturalist. On 5 July 1942 she wrote to Nehru from Srinagar:

“Truly if there is a heaven, it is this. There is nothing in Switzerland to compare with these flower-filled slopes, the sweet-scented breezes. Maybe there are other things besides running water that pour over the soul the anodyne of forgetfulness and peace.”

Half the joy of being here is that there are no crows and no babblers. There are mynas but they are not as noisy as in the plains.

A few years down the road, on 23 May 1945, she wrote to her father again from Srinagar:

“Srinagar is really lovely. After a whole night’s rain, the sky was clear and cloudless and studded with stars, and the mountain ranges glistening silver with the freshly fallen snow […]

I should like to do at least one small trek. In one of the guidebooks, there is such a lovely description of the road to Tragbal Pass near the Nanga Parbat, that I cannot resist the temptation to go and see for myself […]

She went to Kashmir in early May 1945 with her baby boy to escape the ‘rather unpleasant months in Allahabad, full of illness and insect bites’. Writing to her father on 19 May, she said:

“Coming from the plains—the dry, dusty roads, the scorching sun—you can imagine what a relief it was to the eyes to see miles and miles of fresh green. […]

Half the joy of being here is that there are no crows and no babblers. There are mynas but they are not as noisy as in the plains. The birds that are constantly in the garden are the white-whiskered bulbuls, shrikes, golden orioles and different kinds of tits. All such lovely creatures. I am longing to see the paradise flycatchers—they say there are lots here. It is truly a heavenly bird.”

Propelled by the desire to travel and ‘getaway’, Indira Gandhi visited Kashmir almost every year through the 1950s with her sons Rajiv and Sanjay. On 18 June 1960, she wrote to her father from a houseboat on Nagin Lake in Srinagar:

“Today is the first clear day since our arrival & it is truly a magnificent sight. In Kashmir, there is always an element of sadness or is it melancholy. Perhaps it is due to willows & their droopy look reminding one of Davies’s poem on the kingfisher:

So runs it in thy blood to choose

For haunts the lovely pools, & keep

In company with trees that weep.

The boys are busy. Sanjay swims, rows & takes photographs. He is very independent & loves this life close to nature, observing dragonflies and kingfishers. Yesterday, a kingfisher came right into our sitting room—a swift perched on Rajiv’s shoulder.”

Of course, Kashmir offered more than just birds. Indira Gandhi wrote to her aide Usha Bhagat on 26 June 1963:

“We have had a wonderful trek to the Kolahoi glacier. Refreshing. The magnificence and grandeur of the mountains gives quite a different perspective to life. “

Few parts of the world have been so richly endowed by nature as Kashmir. We must therefore be specially careful not to squander irreplaceable assets.

The Dachigam Sanctuary close to Srinagar was Indira Gandhi’s favourite getaway. She visited it numerous times. After becoming prime minister, she began receiving reports about the steep fall in the population of Hanguls (the Kashmir stag) in the sanctuary. On 11 February, she wrote to G.M. Sadiq, the chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir:

“Having stayed in Dachigam several times, I know what a great attraction it could become if the animals are well looked after allowed to multiply. I hope it will be possible to accept and stringently implement, the recommendations of the IUCN, especially in regard to poaching and illegal grazing […]

Few parts of the world have been so richly endowed by nature as Kashmir. We must therefore be specially careful not to squander irreplaceable assets. For a state whose economy depends a good deal on tourism, it would be doubly rewarding to make Dachigam a truly great sanctuary with an international reputation.”

Indira Gandhi didn’t stop with this letter; she kept pressing the issue with successive chief ministers of the state—until the early 1980s when she derived some satisfaction at the impact of her continued concern.

Judged by the frequency of her visits there, the Dachigam Sanctuary near Srinagar was undoubtedly one of Indira Gandhi’s favourite spots. In February 1981, she had helped Dachigam’s status get upgraded from that of a sanctuary to a national park. This was mainly because international conservationists, including those in the IUCN, had been expressing serious concern regarding the rapidly dwindling numbers of the Hangul because of poaching and the loss of habitat.

G.M. Oza — a well-known botanist and activist who, along with Fatehsinghrao Gaekwad had launched an Indian Society of Naturalists in Baroda—had been studying the Hangul closely. He wrote to Indira Gandhi on 26 September and a preoccupied prime minister replied four days later. His request to her was to release a special postage stamp depicting the Hangul, Indira Gandhi, did so on 1 October, at a meeting of the IBWL. She added:

“I am delighted that we have a postage stamp on the Hangul. But this is not sufficient. I agree that we must focus attention on the need to protect the Hangul, its habitat and the floristic elements necessary for the Hangul’s conservation. “

Soon after, the newly appointed Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir Farooq Abdullah, with whom she was to have a bitter political falling-out a year later, sent a very encouraging message. On 7 October, she thanked him for his assurance that ‘the Hangul shall never die’ and added:

“We know of the interest which Sheikh Sahib [Sheikh Abdullah] took in wildlife conservation. I hope that these efforts will be further strengthened under your stewardship.”

Laws passed by Parliament do not automatically apply to Jammu and Kashmir—where the state legislature is empowered to pass its own laws. Thus, the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 could not by itself be enforced there.

Indira Gandhi had been, from time to time, getting reports from Kashmir on the sale of the skin and fur of animals on the banned list. On 16 December, she told Kashmir’s Chief Minister Syed Mir Qasim that the ‘fauna not only of Kashmir but also of the entire country will continue to be subject to the caprice and greed of tourists and traders’. She added that by not adopting the 1972 Act, the state had created a ‘premium on the illegal killing of endangered species, including those whose habitat is Kashmir’. She went on showing her knowledge of and concern for the state:

“I do appreciate that a considerable number of Kashmiris are engaged in the fur and skin trade. But there seems to be a misplaced apprehension among them that the adoption by Kashmir of the Central law will deprive them of their livelihood. This is not the case.

It is true that items like the tiger, panther and snow leopard have the greatest snob value and command the highest price. Fortunately, however, they constitute a small fraction of the total turnover of the local trade, both in value and volume. For items of bulk sale like gloves, fur caps, fur-lined leather, suede jackets, local animals like the weasel, musk rat, hare, marmot, otter, stoat, pine martin, flying squirrel and fox are used. These will continue to be available to them even if J&K adopts the Central law, with this difference only that the trapping will be controlled through licenses issued by the Forest Department in order to ensure that these species do not become extinct by excess catching […]

The furriers also use domesticated animals like sheep, goats and rabbits. No permits are necessary for these or for jackals […]

[…] Kashmir’s adoption of the Central law will be a notable victory for the wider cause of conservation.”

It wasn’t just Agra’s pollution levels that concerned the prime minister in 1983. Kashmir, undoubtedly her favourite state for a quick holiday, had been getting increasingly polluted, and the prime minister mentioned this to her officials. The chief minister of the state was close to her personally—but at that point, he had been making common cause with her political rivals. Even so, she wrote a ‘Dear Farooq’ letter on 15 March:

“The increasing air pollution in Srinagar has been worrying me for a long time. I understand that the problem is compounded by road transport vehicles which are not well maintained. There are some long-term measures […] which would bring about significant improvement in lessening the emission of pollutants of these vehicles. But in the short run it would help if these vehicles are checked by road transport authorities […] At some stage you should also think of legislation in this regard which is suited to local conditions. I understand that army vehicles in Srinagar are well maintained and do not add to pollution.

Please let me know what action you propose to take in this regard. “

A month later the chief minister replied to her, promising a series of steps that he would take to address her concerns.