After winding up its half-a-century-old gory shell-campaign at Tosamaidan in 2014, army is exploring alternative area. Bajpathri, the fascinating meadow between Pulwama, Budgam and Rajouri is one option. Kashmir Life’s photo chief, Bilal Bahadur trekked up the hills to rediscover the meadow and return with concerns at ground zero

The Fajr, the wee-hour prayers were over and the twilight was gradually paving way for a clear vision. It was the melody in His praise dished out by the mosque loudspeakers when I left home.

On the road was my bike breaking the ground silence with a few joggers – no traffic snarls around. The entire road belonged to me. I was driving toward Nagam, a dusky village in the central Kashmir’s Budgam district, my base station for a trek to Bajpathri, a meadow deep into the woods separating Budgam from Pulwama. This meadow was in news for almost a year. After the revelation that Bajpathri is becoming new army firing range in Kashmir, a signature rage erupted and faded almost instantly. It was talked about loudly. I wanted to see and capture it.

It was May 18, 2016.

It was still early dawn, precisely 5:50am, when I reached Nagam, the village barely 5km short of Yusmarg. I saw residents sluggishly starting a new day. People were crowding out of the local mosque after completing the elaborate morning prayers. With pitchers on their heads, women were on way to the local stream to fetch water and keep the yarbal active.

I found my host waiting. Ghulam Mohammad Ahangar, the Sarpanch, village head, quickly responded to my knock at the door. We met, exchanged pleasantries, and sat for a quick breakfast – salt tea and the Tscutch Wuer. Soon, Mohammad Isaq joined us. A young man and a local panch, he was tasked to be my guide for the trek. Within next 15 minutes, we left our host and got into thick woods and towering peaks on the fascinating journey.

Thirty minutes of uphill trekking was cut short by an encounter with two Gujjar women, washing utensils near their hut, located deep into thick woods. In the backdrop of breathtaking green cover and fresh water stream, it seemed a blissful life, a Shangri La, literally. Far away from the modernity of ‘connectivity’, these people are spending part of the year with their herds in the nature’s lap.

But the very assumption got dashed when we met two men coming out of the woods we were heading to. My presence alerted them.

“Who is this?” the duo asked Isaq, who was no stranger around, curiously.

“He is a journalist from Srinagar. He is here to capture pictures of Bajpathri.”

After knowing my identity, I could see their changed facial expressions. They came closer to reveal what was perhaps troubling them for some months now. They were more willing to talk.

“Do you know what army is up to here?” one of them sounded as if he was about to blow a cover over some clandestine development. As I expressed my ignorance, he felt shocked and hastened to add: “They are axing trees here to pave way to the proposed firing range!”

Some 350 trees already stand marked for the cutting exercise, he said. “Something needs to be done to stop army – otherwise, the place will have worst fate than Tosamaidan!”

After registering their tensions and revealing a bit of what they know, the two men left. Isaq said they were forest officials.

For the first time, I realised that my journey was about to become more than an adventure. The duo left me with many questions. Are trees really being axed? But where were those marked trees? I understood that what is known down in Srinagar as army’s combing exercise to explore Bajpathri as new firing range is in fact a truism.

Then the meadow started revealing things.

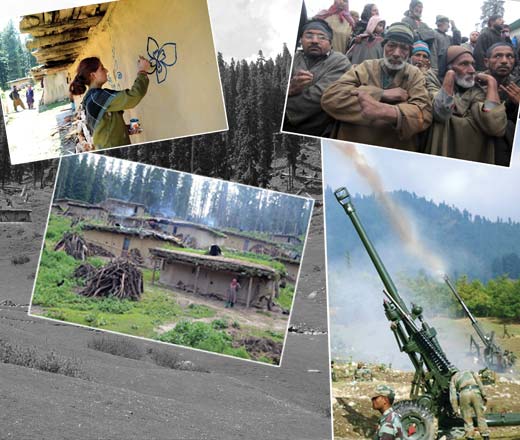

Shortly we reached Tarak village, a few miles short of Bajpathri. It turned out to be another heavenly spot, full of bewitching beauty. At some far-off corner, a blonde Gujjar girl was engrossed in painting her hut wall with a blue rose. Unaware about the silent simmer gripping her tribe, the girl, who lived by her name, Haseena, talked how she loves to paint flowers.

For that class-X student, the idea of life was simple: stay closer to roots. But if the larger prevailing mood was any indicator, then she might lose her roots anytime sooner, much to her heartbreak, I reckon.

This surging sense of ‘getting uprooted’ was making her clan to lose their calm. I have captured countless frames depicting unspeakable fears across valley. My own experience tells me, fears don’t keep calendars in Kashmir. They unleash unannounced, without warnings. But what I was beholding at Haseena’s hamlet was different. It was a perpetual state of fear where the announcement came before the arrival.

I continued trekking uphill leaving her at peace with her painting. Shortly I was walking besides a serpentine water-body called Sangam. It acts as the borderline between district Pulwama and Budgam. I was in Budgam part, where tensions were silently peaking up against the explosive proposal. At a stone’s throw, three Gujjar men cut me short, again.

They wanted to know who was the stranger prowling in their vicinity flanked by a well-known local face? The moment they had my introduction, they instantly lost their tempers.

“Army thinks they can make hell of our heaven,” said one of them, frothing with fury. “They are mistaken! We will lay our lives to guard our homes.” They were angry and their anger was primarily stemming from the threat of losing their homes to the shell campaign. I couldn’t stop drawing parallels. Last time, I saw the similar fears at Tosamaidan.

In 2013, it was a simmering summer at Tosamaidan. Some faint cries of resistance against army’s shelling practice there had reached Srinagar. But the campaign was yet to rattle the power centre in summer capital. To capture the emerging story, I along with my colleague visited the ‘meadow of death’ to report the ground mood. We were perhaps the first ones to explore the shell campaign at Tosamaidan in detail. But I never knew that I would return home with gigabytes of horror images: limbless, armless, impaired and distressed portraits of the villagers.

In Shanglipora, almost the entire village paraded their mauled ones before my camera. I almost broke down over the scene where the helpless were getting lined up to highlight their inflicted distortions. Fifty years of artillery drilling hadn’t only devoured their breadwinners, but also made their lives tormented one. Fathers, brothers, mothers were gone with the bang.

Will Bajpathri become a mirror image of Tosamaidan, I kept thinking!

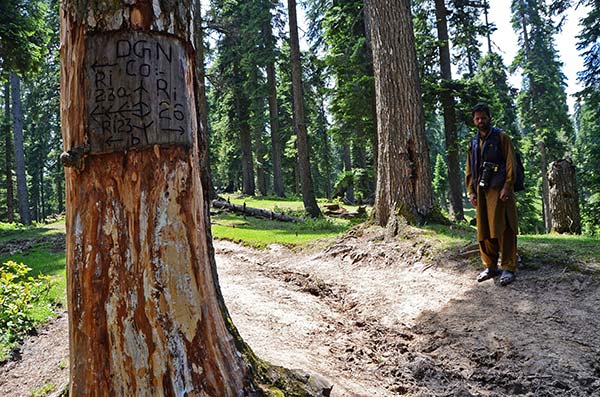

Our next stopover was the locale where the first signs of army’s ambitious move to set up a firing range became obvious. I – for the first time – was looking at the marked trees as mentioned by the two forest officials I met downhill. They were marked with some coded language. Even my local guide, well versed with every sign and symbol in the area, wasn’t able to decipher the language: DGN, CO, RI, 23a… The code was freshly engraved on the trees.

I had my prized click – rows and rows of lush green young trees marked for axing. I started thinking, when these trees fell, bald men would be more beautiful than the meadow.

While walking past several such trees, I stepped in Bajpathri — the final supposed destination of my trekking. The first sight simply stunned me. The beauty of the bowl-shaped meadow was overwhelming. It was breathtaking, unspeakable experience. Never in my 14 years of journalistic career have I come across such a breathtaking spot. “Just think about it,” Isaq told me, “what would be the fate of this place if army would resume their shelling here they suspended in Tosamaidan.”

There were no readymade answers, not even thoughtful ones. It was like asking someone: How do you feel being mauled over? I am no greenhorn. My experience of years have tested and put me in similar situations, where in the face of such questions, I could only offer my damned silence. In Bajpathri, my damned silence once again reigned supreme.

But to my surprise, my journey didn’t end at Bajpathri. Isaq, the trek-hardened man, took me further uphill. He was taking me to the spot where army’s shells will land if fired from Bajpathri. The place was Charkhal.

Needless to say, Charkhal turned out to be even more beautiful spot in the belt. By the time I reached there, I was already trekking for over three hours. There, I met a roaming shepherd, Mohammad Akram. He was sensitive enough about the prevailing mood in his hamlet. “If somehow the firing range comes up in the area,” he said, “it will destroy everything here.” By the time he finished speaking, five men appeared. They were locals, looking no different from the shepherd: anguished.

I was taken inside a hut, where some ten members huddled to fix absorbed gazes at my face. From their looks, it was quite certain that they were perhaps weaving a web of imaginary hopes with my visit. I was their messiah, perhaps! This is the common experience we journalists face in the line of duty. But I was not there to raise hopes, but to discharge my professional duty to the best of my abilities. I just wanted to capture their story as it is.

My thoughtful stance broke when an elderly person sporting henna-dyed flowing beard told me, “If they want to set up that death theatre in the name of firing range here, then let them send us first to either China or Pakistan!”

The conversation spanning over 30 minutes was filled with a sense of concern, confusion and calamity. “They think we people will bow down before them. They are mistaken! We will sacrifice our men, women and children to protect our land.” With each word spoken by the elder, the faces inside were becoming sullen, deeply sullen.

Later as I stepped out of the hut, I could see vast swatches of postcard land before my eyes. While catching my glimpse, the elder Khan pointed his finger toward the green cover downhill and said: “Can you see that spot?” Without waiting for my answer, he said, “it connects Pir Panchal areas of Rajouri and Poonch with Kashmir. So the proposed firing range won’t only doom this part of Kashmir, but also parts of Jammu as well.”

Almost the entire Gujjar clan was out, listening avidly what their elder was telling the visitor. Around 150 huts exist in Charkhal, each averagely populated by five family members.

Just before I could take an alternate route to Nagam, the elder told me how army did rounds of the belt at a time when Tosamaidan Bachao movement was creating ripples in twin power centres of Gupkar and BB Cant. Under fire over the civilian casualties by stray shells in the meadow, I was told that army was seen in Bajpathri, marking the area with lime powder. They had come to claim their new piece of land.

“The army’s sudden arrival unnerved us,” said the Khan. “To clear the confusion, we met then chief minister Omar Abdullah and army officials in Srinagar. We were told that it was essential for army to have firing range in Bajpathri to relieve them from going to Himachal Pradesh for the trainings. When we raised our concern, we received dubious answers.” And since then, the villagers have been finding themselves on literal tenterhooks.

With a streak of fear trailing, I took an alternate route downhill. I was now walking on the other side of Sangam. On my way, I saw a series of sites of tree massacres. Isaq told me that massive axing of trees has been underway in the area for some time now. Before I could join some dots, I was told by a local farmer, “felling of trees got boosted after it was declared that army is coming here to setup its base.” Even smugglers were making hay while the sun was shining! Those lived experiences of natives were indeed clearing the fog over Bajpathri.

Shortly, my weary feet took me to the three fresh water ponds, fed by Sangam. Close at hand, as I crossed two small wooden bridges, I reached another Gujjar community comprised of 250 huts. One of the community members I met expressed concern over what he called the threat to his forefather’s hutment.

As we strolled while conversing back to the three water ponds, the man stopped, saying, “These PHE-run water reservoirs supply drinking water to Srinagar and Chadoora. Now, imagine their fate and fate of the areas they supply water if firing range comes up here.”

By then, it was already sundown. As I reached back to Nagam, I met the Sarpanch, who was vowing along with his daughter and other family members to put up one last battle to prevent the resurrection of Tosamaidan.

Amid dusk, as I kick-started my journey back to Srinagar, I couldn’t stop thinking about the young girl, Haseena, and her artistic acumen to paint blue rose on her hut. Blue being a ‘symbol of sadness’ perhaps highlighted the larger prevailing mood in her community.

But, I keep asking myself, can’t world’s largest democracy let the kid be at peace with her painting—unless, yes: force change her canvas by replacing her rose with her rage?!

-As told to Bilal Handoo