The art of depicting the lifestyle of erstwhile Mughals rulers on papier-mâché is fading into history. Mohammad Raafi traces one of the last surviving artists who is struggling to survive the neglect

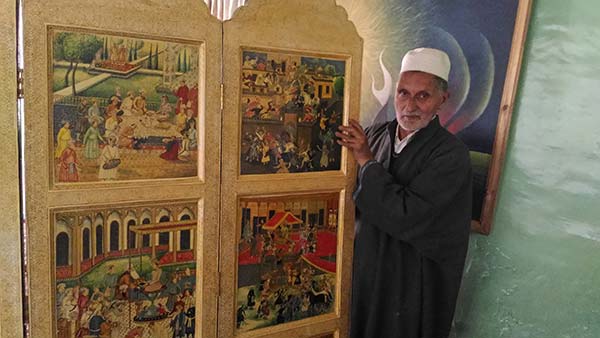

On a late October afternoon, the air inside Srinagar’s Saz’gaerpur Mohallah in Hawal, is heavy with antiquity. In the courtyard of a small house, a makeshift ‘factory’ stares like an oddity. Inside the factory, Munshi Ghulam Muhammad, 80, is carefully painting a piece of papier-mâché. His delicate strokes defy his fading years. The walls of Kaarkhana (factory) are decorated with awards, certificates and mementoes Munshi has earned over the years for his craftsmanship. He sits surrounded by colourful papier-mâché dry fruit boxes, pen stands, jewellery boxes etc. like a proud man. But one of his prized creations is a Wooden Screen painted with Mughal art. “I finished this Screen 11 years back. Since then I am waiting for a customer who could appreciate my hard work,” says Munshi.

The Wooden Screen that comes with a price tag of Rs 5 lakh, took Munshi 18 months to complete. “I would be happy if anybody appreciates my efforts. But if I don’t get the desired price, I am happy to keep it with myself,” says Munshi.

Munshi is one of the few surviving papier-mâché Mughal artists in Kashmir. “I have been working on Mughal art motifs for nearly fifty years now,” says Munshi, lamenting the fact that successive governments have neglected this precious art form. “I fear this art will die with me. There is hardly any artist left who could understand Mughal art. Besides it is hard to survive as an artist in this machine age.”

With customer base shrinking fast because of lack of promotion and less foot-fall of tourists, Munshi feels it is difficult to earn two square meals even. “How can you expect the new generation to take up this art? They know it will not earn them anything,” says Munshi.

But things were not always as disappointing as they are at present. The lovers of Kashmiri Mughal art were once spread across continents. “A very famous barrister from London was among my regular customers during 1970s. Even Indira Gandhi purchased my products from Suffering Mosses’ showroom in Srinagar,” claims Munshi who worked with the showroom then.

It is believed that Papier-mâché, also known as Kaar-i-Kalamdan or Kaar-i-Munakash, came to Kashmir in the early 15th century. According to historians, it was because of efforts of Mir Syed Ali Hamdani, a Persian Sufi saint of Kubrawi order, who travelled to Kashmir along with his seven hundred followers that art and crafts flourished in the valley. These followers mostly comprised of artisan and craftsman.

The art of making pen cases from the mashed paper was known in Seljuk Iran; from where it spread to other parts of Central Asia including Samarkand. However, because of metal and wooden pen cases in demand in Iran and other Central Asian countries, kar-i-kalamdan or papier-mâché failed to find footing in these regions.

“It was from Samarkand,” says Hussain Joo, a well known papier-mâché artist,“That Zain-ul-Abideen brought artisans well versed in the art of kar-i-kalamdan or papier-mâché.”

Traditionally there are three basic designs in papier-mâché: figurative, floral and geometrical depictions. There are hundreds of motifs that come under these three categories known as Tarah. “It (Tarah) depicts entire canvas of Kashmiri papier-mâché art including Hazarah, Gul-e-Wilayat, Gul-andar-Gul, BadamTarah, Sarav, Islim and Chinar,” says Munshi.

However, during Mughal rule in Kashmir, a new motif was added to the list called Mughal art.It would depict Mughal rulers and their lifestyles on papier-mâché items.

Back in 2015, Munish is struggling to survive as an artist. However, during his heydays as a Mughal art knowing person, Munshi used to earn handsomely. “My products would adore walls of famous showrooms like Suffering Moses, Ali Shaw, Shaw and Shaw.”

Back then Munshi would feed a large family of eleven members with his earnings. “Now it is difficult to even feed myself.”

Munshi claims that his products were exhibited in London and Paris during the 1980s. “I would receive huge orders from foreign buyers.”

However, the situation completely changed after militancy broke out in Kashmir in 1989. Suddenly foreign tourists, who were major contributors to the state’s economy, stopped visiting Kashmir. “We went out of business completely. Our livelihood was directly connected to the arrival of tourists.”

Munshi started his career as a simple artist and learned Mughal art from Ali Muhammad Burkha, a famous artisan from Kamangar-Pur in Shehr-e-Khaas. According to Munshi, Burkhawas a recipient of American King George Award. “You can now imagine how popular this art was.”

Apart from the prevailing situation in Kashmir, Munshi also blames exploitative businessmen for artisans’ pathetic condition. “They would sell our products for thousand but pay us just a few hundreds,” says Munshi. “This is where the government failed us. They (government) failed to protect our rights.”