It is a family that never sent any of its wards to any business schools, but in last 150 years, it has evolved a family business into an empire such that the accumulated expertise could be an IIM resource base. A Kashmir Life report.

Resilience to the adverse situation gives this family a competitive edge over many others who downed their shutters and fled. “I am the sixth generation trader and I am as proud a Kashmiri as you are,” says Vinod Malhotra of Tirath Ram and Co, a major textiles wholesale concern operating from S R Gung, known as the old city in Srinagar.

“Within three days of my massive go-downs going up in flames I resumed the routine from this house and this all was not outcome of my efforts alone.”

Malhotra’s great-grandfather Lala Kutmal came from Multan somewhere after 1850 and started his business from SR Gunj in the old city. Now it is their permanent address. “He had had eight sons and perhaps four daughters and all the Mehras’ and Malhotras’ who are in Kashmir are from this clan only,” says Vinod. “But we are still known because of my grandfather Tirth Ram who was respected across the city for his philanthropy and good business.”

Malhotra belongs to one of the few non-Muslim families who still operate from the SR Gunj, the market that was a business hub at the peak of Dogra autocracy.

Last month Malhotra lost one of his business premises in the area to a major fire in this small antiquated market. “We store textiles, brand and make-wise, and tragically it was the precious section that caught fire in the middle of the night,” informs Vinod.

Two days after it was still smouldering when he decided against operating from an adjacent house that serves as their warehouse. Instead, he went into a by-lane to operate from the house where he was born and brought up.

The market apparently set up around 1871 by Maharaja Sri Ranbir Singh (and named after him), is one of the many small markets on the banks of Jhelum. The river was the main carrier of men and materials then. The rectangular market around a small park still has a major opening towards a terraced bank suggesting that the kings and courtiers would visit it taking the river route along with boatloads of merchandise. Initially, the relatives of the kings and their courtiers had set up shops and with the passage of time, the others also entered the otherwise prestigious market.

Conflagrations have been visiting this market off and on. Locals believe that, initially, the autocrat or his agents would come for interactions with their subjects here. It was a fire that forced them to convert it into a wholesale market. But that did not prevent fires from visiting SR Gunj, popularly known as Maharaj Gunj. Of the four sides, the fires have forced an architectural shift on two sides.

“We are facing a peculiar problem here,” says Rouf Ahmad Punjabi, a prominent businessman and a former president of Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry. “The narrow roads are a major problem for the shoppers, and a bottleneck for fire-fighting.”

Vinod says the gutted warehouse was 197 years old and in their use for over 100 years. “Money comes and goes but we lost some of the prized possessions like the photographs and old records that were of heritage value,” he said. But if the government includes restoring this market to its past glory, it can still be done.

Vinod was born in 1947 in the house he is operating from these days – a three-story complex that could be a great entry into the city’s heritage buildings list. “In our Hamam, we had the newspapers of 1947 pasted on window panes. We recently cleared them,” he said. From balcony to the basement and from dormitories to bedrooms it is stuffed with cloth – of all companies and all brands.

For the family that has traditionally been ‘importing’ fabrics and textiles, the days of the partition were a bit difficult. “Our family temporarily shifted to Amritsar for a few weeks after handing over the entire business to our trusted domestic help and a tongawalla (cart puller),” says Subash Chander, Vinod’s elder brother. “Our father told us that when we returned, the entire business was not only intact but thriving too.”

The subsequent turmoil did not impact the family that way. “I vividly remember the 1965 war. One day I was cycling back home from Chattabal when I saw the Pakistani fighter planes flying very low over Srinagar,” says Vinod. “It was a rare sight because Kashmir had never witnessed an aircraft so closely. I saw the girls of the Women’s College Nawakadal fainting on the road and many people on top of their houses in praise of Pakistan.” But the war had no impact on the business. The 1971 war was too distant to have an impact at all.

The militancy that broke out in 1990 was a real challenge. “Even when it started with bomb blasts we would work till 12 in the night,” Vinod says. “Sometimes it would invite local residents who would strongly advise us not to take chances but we continued because there was no option, the clientele was huge and unmanageable during day time.”

The Gaw Kadal massacre changed the situation altogether. “People started fleeing and the killing of son of the owner of Krishan Flour Mills added to the panic,” he said. The family shifted its womenfolk and the aged out of the valley and the two brothers – Subash and Vinod stayed put.

Despite the suggestion from Muslim friends to shift out, they stayed put. “People came to me and everybody gave us something – somebody gave Kangris, another gave a tracksuit and somebody a pair of socks. I still do not know who they were. But these small things were a huge encouragement,” admits Vinod. For this, he credits the reputation of his family in the local society.

With their families out, the two brothers would work as the shortened days would permit. “It was a different work culture dictated by a changed situation,” Vinod says. “We had two gates opening on two sides. If it was a crackdown on one side we would flee from the other gate.” For all those years, the two brothers swear, they were solely dependent on their trusted staffers. “We would just monitor sitting in a corner and they would run the business.”

To incidents around, Vinod says, he would react the same way as the Kashmir’s should react. “There would have been countless instances I was caught in crackdowns,” he said. Many times he would be asked to go but he says he never obliged the security men because “I being a Kashmiri can never take the benefit of my faith”.

One instance, he says, he remembers vividly. “There was an officer who would like to be called as Kaliya. In a crackdown he ordered me to get up,” he said. “After asking me my name and faith he asked me why I had not fled and If I was not afraid of death. When I said it is all up to God, he said ‘The same Allah you are referring to will kill you.’ But see the fate,” says Vinod, “He was killed in a blast and I am here doing what my ancestors have been doing.”

It was not that they remained untouched by the situation. “They (militants) once took me and I told them I am as proud a Kashmiri as you are. They left me without any harm,” said Vinod remembering how the locals rallied behind him. There were protests in the market that built a lot of social pressure on his abductors. “When I was set free, I saw people hugging me like anything – men and women,” remembers Vinod. “Later when I met my mother, she broke down and I told her – your tears are not as precious as those of the women in Maharaj Gunj who shed tears in joy after I was set free, simply because I have a blood relation with you and they have nothing.”

Malhotra’s’ have enough resources for taking any studies or careers but the business has always been their first love. Subash did his masters in bio-chemistry from Lucknow in 1965 and had an opening in California for further studies but he joined his family business.

Their elder brother Ashok Malhotra is a doctor but instead of going to any clinic, he looks after the family’s business operations in Amritsar. The credit, says Vinod, goes to their father Lala Lal Chand Mehra who once got all his three sons to his room and told them that the business will provide them more than what the government will. “Since then, our business increased 100 per cent and right now we have over 300 employees from Srinagar to Amritsar and the major clients have gone up to 500,” informs Vinod.

Vinod’s son Vikram and Vishal have passed out from Bisco and joined the business (the family has three generations of Biscoe passouts and their grandfather was part of the school team that sailed the Wullar, a historic landmark the school has set. Of Dr Ashok’s two sons, one is in business and another is a doctor. Sushil, Subash’s lone son has decided against business and is an IT engineer in the USA.

The family does not talk about its turnover believed to be in billions but are transparent about what they are doing. “We work with all the major textile companies in India. We mostly work in contract manufacture,” says Vinod. “We place orders for what we require in Kashmir market. Besides we have our own brand ‘SC’.”

The family says that Kashmir is a lucrative market for fabrics and perhaps may top the per capita consumption of the textiles. “Primary factor is that you have four seasons which requires different sets of attire,” explains Vinod.

Vinod’s is, however, not the only non-Muslim family that is staying put with its business in the old city that many would like to project as the most vulnerable place in Srinagar.

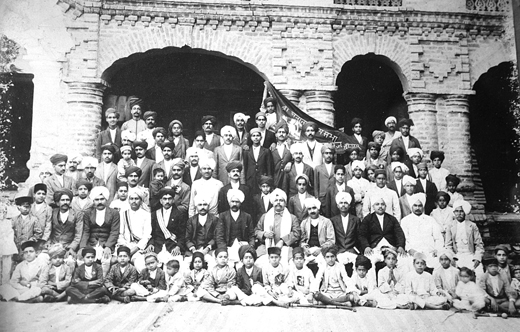

Unlike Vinod who, off late, lives in uptown, there are two families Gandotras and Malhotras who live in SR Gunj. Anil Kumar Gandotra is a provisions wholesaler whose family lives in this locality since 1867. “It always was a home,” he says while handing a 1932 photograph of the SR Gunj Beopar Mandal in which Tirath Ram is sitting like a Liliput in the front row – kids of the businessmen.