Part of the faith heritage, shrines help decipher Kashmir’s historic and socio-economic narrative. In twenty-first century, a shrine is lost to a fire every five years. Though different government agencies have taken various initiatives to prevent the recurrence of fires, there is a serious lack of clear and comprehensive policy about how to assess the hazards and how to manage them, reports Masood Hussain

Kashmir went into instant mourning when the spire of Khanqah-e-Moula caught fire and was destroyed. The early morning fire also damaged part of the roof as well but the main edifice survived the instant conflagration.

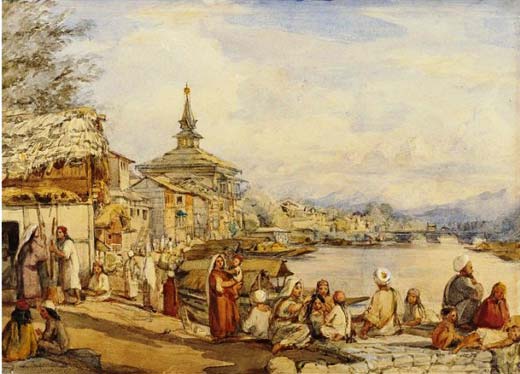

Kashmir has a chain of Khanqah’s, one each in Tral, Sopore, Vachi and Pampore. But the Srinagar Khanqah is more important because of it the oldest of them all. Situated on the right bank of the Jhelum River, between Fateh Kadal and Zaina Kadal, it is not the first mosque of Srinagar but it undoubtedly is the first Khanqah in Kashmir. Khanqah’s are praying spaces attributed to saints which are mosques, meditation centres and even schools of Islam. Khanqahi set up is at the soul of certain Sufi orders.

A mosque already existed by the time Mir Syed Ali Hamadani came to Kashmir in 1372. He came again in 1379 and finally in 1383 before he passed away in 1385, almost a year after bidding adieu to Kashmir. In 1393, his son Syed Mir Mohammad came to Sultan’s rousing reception in Kashmir. The king, two years later, gave him the responsibility of supervising the construction of Khanqah in memory of his father, the Amir-e-Kabir. In fact, Sultan Sikander (1389-1413 AD) funded the construction of all the Khanqah’s in Kashmir. There are, however, historical references to the existence of a Khanqah in Srinagar prior to Amir-e-Kabir’s arrival.

The shrine might have changed a bit of form but by and large, it has remained unchanged in its broad structural details. Once surrounded by various Chinar’s, the shrine is one of the distinct structures that offers an impressive fusion of Hindu, Buddhist and Muslim architecture. The two-storied, two-tiered Cedarwood shrine sits on a square plan, erected on irregular walled base. It has sloping pyramidal roofs demarcating each tier as the roofs are accentuated by woodwork adorning the cornices under the eaves. Its “beautifully carved eaves and hanging bells” have historically been considered as its aesthetic feature.

Mohammad Salim Beigh of INTACH said while constructing the building, the builders have exhibited technologies endemic to Kashmir. “It is a wooden structure that has brick fill-in,” Beigh said. “This has been done to prevent any damage from earthquakes which were more frequent in various eras of the medieval history.”

But the fires could not be controlled for most of the history. Though this shrine is believed to have survived with some damages many times, two incidents are mentioned by almost all the historians. It was gutted in the fires in 1480 and was reconstructed by Sultan Hassan Shah in 1493. It caught fire again in 1731, at the peak of exploitative Afghan rule and was reconstructed by the then governor Abul Barkat Khan, a year later.

Afghans did a Himalayan intervention by sending the families living around it to some other place. This was done to create a safe zone and de-link the shrine from the habitations in order to prevent fires. They also added a number of small Hujras, chamber rooms, to the shrine so that more people could have isolated spaces for mediation. Originally, it had only one.

The shrine, however, faced an existential crisis at the peak of the ruthless Sikh rule. They were told that the shrine has actually been built on the ruins of a temple. In order to restore the property to Hindus, Beigh said, the Sikhs actually installed heavy guns around it in order to destroy it. “There was an influential Pandit Birbal Dhar Kak who was approached by Muslims with the revenue papers showing the land had actually been purchased by the Muslims when it was constructed. His intervention prevented an action.”

Beigh said the fact is that there was a Kali Mandir, very close to it. The temple was active and open for prayers till Pandits migrated, he said.

Barring creation of a gate, there have not been many interventions in the shrine for last more than a century. Officials’ privy to the developments said that the last intervention – apart from paints, electrification and other basic things, was to block the first story open space by raising windows. This was done to prevent pigeons from getting into the shrine. This, experts said, could have been managed without adding windows into the shrine. It has intricate and characteristic woodwork and carvings, besides, massive papier machie work on walls and ceilings.

Some historians’ like the famous Parsi intellectual J J Modi have recorded its significance for the inscriptions that exists within and outside the mosque.

Even for the recent political history, Khanqah holds a major landmark status. It was there when Qadeer Khan spoke, triggering events which eventually led to the happening on July 13, 1931, Kashmir’s Martyrs Day. In fact, the seven delegates who were elected for raising the issues of the people and talk to Maharaja were also elected in the same premises.

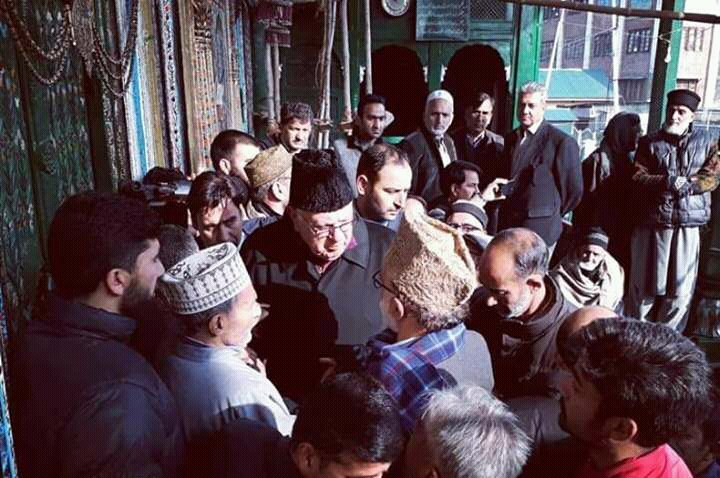

As the spire caught fire, Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti cancelled all her engagements and flew to Srinagar with Altaf Bukhari in tow. So did Omar and his father Dr Farooq. Mirwaiz and Malik were also there to mourn the loss. Locals said that the respect to the shrine, cutting across political and ideological lines, would have meant a lot had there been a consistency in concern, even when there were no fires.

Khanqah losing its spire in lightning, as is widely believed, is perhaps the first instance of its kind in recent history. Incidentally, people surrounding the shrine, especially the 52 Anwar’s families, having stakes in its economy, say that the shrine took the hit that was basically aimed at the locality. Bt this is not the first instance in which a shrine was hit by a fire. The last instance is that of Dastgeer Sahab shrine in Khanyar that went up in flames within minutes on June 25, 2012.

A number of shrines, mosques and structures of historical importance were destroyed by fires in last many decades. After the Khanyar shrine, a mysterious fire destroyed the all-wooden shrine of Lalbab Sahab Ziyarat and the adjoining mosque in Sopore on October 19, 2012. Prior to that on July 16, Baba Haneefuddin’s shrine in Ratsun village of Budgam was completely destroyed.

Khanqah’s, the Jamia Masjid and other shrines within and outside Srinagar, the Shehr-e-Kashmir, are key spaces fundamental to Kashmir’s historic, cultural and, to an extent, the spiritual narrative. Governing structures have been using pro and anti-shrine debate for many decades to divide the people on basis of traditional and puritanical strands of the faith. It has remained a key factor in politics of the place. But now there is an increasing realization that while shrines lack an importance in comparison to a mosque, they still are vital as socio-cultural relics to history, architecture, and archaeology and required to be preserved and protected. Their significance as part of Muslim heritage is unparalleled.

But the tragedy is that while Kashmir has a huge mass of such structures, it lacks a clear policy on their protection. “These issues crop up in media when there is a crisis but then it fades away from the public debate,” Rafi Ahmad, the top officers managing Kashmir’s Wakf Board said. “It has to have a consistent attention from the society which is more important.”

Neither of the shrines in their present form is less than 200 years old. If every harm, natural or man-made, skips, there is decay which is natural. A recent media report said that a SKUAST expert team has found 36 eastern side Deodar pillars in Kashmir’s Sultanate era Jamia Masjid having pinhole infestation.

The mosque has more than 3000 60-ft tall pillars and most of them are as old as 600 years. This is natural that the wood will have this issue. They have identified the source of the crisis as well. The damage is caused by “dust like powder frass”, a mixture of faecal matter and food fragments, which is fallout from exit holes into small piles on the surface of wooden logs”. All these pillars are located very close to a drain running parallel to all the pillars. Moisture content at the pillar bases was seen high so the decay will appreciate. Left untreated, this crisis will hollow the pillars.

Experts, according to reports, have suggested plastering of pillars, better ventilation and injecting certain things in the pillars.

Salim Beigh of INTACH said it is treatable. “We had a similar crisis in Aali Masjid,” Beigh said. “The pillars stand but are yet to be treated.”

“Chief Minister took an urgent meeting in which audit and assessment were ordered for all the shrines and most importantly Deputy Commissioner Srinagar was asked to preside over the entire monitoring set up,” Rafi Ahmad said. “What makes it different than earlier similar decisions were taken but the follow up lacked for want of ownership of the protection mechanism. This time, DC Srinagar has been given the entire authority and the resources would also flow through his office.”

But the heritage does not face smaller issues. “While hazard assessment will start, there are countless hazards,” Beigh said. “Not a single shrine or historic building has any protection against the lightning, for instance.”

Beigh said that while certain hazards may not be practically controlled the society and the managers must follow common sense in reducing the threat to this heritage. “Why combustible paints and varnishes should be used in these precious structures?” he asked. “Use of electric gadgetry also needs a massive caution. If we need to amplify voice (for Azaan and Daroud-u-Azkaar), why should huge network of the speaker be installed that requires a lot of wiring and once it is wiring, it is electricity.”

“Is not it common sense that when we need to have lamps, which kid of lamps should get into a historic structure?” Beigh said. “And is it not possible that rather than creating a mesh of electric wires from all ends, can not we take one side and be very conservative in managing it? Why can not we have fires resistant wires?”

Khanqah’s spire fire had no electrical issues. But the fact is that it had various halogen lamps installed in and around it. Halogen lamps emit ninety percent heat to offer ten percent light, Beigh says.

Beigh said in a meeting when he asked the Director of Fire Services if he had any idea of the existing fire hydrants in the city, he responded that he has 110. “Then I asked him if there were fire hydrants in the Dastgeer Sahab, why he used the dirtiest waters from Baba Demb, he shouted saying, ‘why should I be part of a meeting that humiliates a Director General rank officer’.”

The fire hydrants have been a Maharaja era facility. Till 1990, officials from the Fire and Emergency Services would regularly visit and check the functioning of these hydrants on weekly basis. The practice was later abandoned. While some hydrants were covered by the black-topping of the city roads, there are various existing ones which are seriously compromised. The one located near the Khanqah mal-functioned last week.

Rafi Ahmad said that all the shrines have captive firefighting stations and they respond quickly to the mishaps. “But I agree, the entire protection system should be given to one competent agency because it does not work that I give firefighting to one and electricity to another,” Ahmad said.

“These challenges cannot be taken in compartments,” Beigh said. “This needs a comprehensive re-look and creation of a formal policy that is implemented as quickly as possible.”

In wake of Dastgeer Sahab conflagration, Beigh was part of a series of meetings aimed at reconstructing the shrine and preventing such disasters in future. He even made a prolonged presentation before the cabinet in July 2012, then presided over by Omar Abdullah, in which he listed 130 possible threats to the majestic Khanqah. His insistence that Dastgeer Sahab shrine has to be replicated in the form it existed earlier – and not in concrete as a minister and a member of the Wakf Board strongly recommended (to prevent recurrence of fires), led to the Wakf members’ resignation. “My whole point was that devotees need to have the shrine in the form and with the material it earlier existed. Converting a replica in concrete will complete falsehood,” Beigh said. The project, mostly complete, is still with the state-run Project Construction Corporation (JKPCC).

Off late, there has been an emphasis on recreating the shrines using a lot of concrete. Earlier it was done in Naqshband Sahab. After the shrine was recreated and extended, the government planned creating a minaret in memory of the martyrs of 1931 which would have dwarfed the status of the shrine itself. That was stopped at the last moment.

Most of the oldest shrines which were reconstructed in last three decades have lost part of the features that the original structures had. Chrar-e-Sharief shrine, for instance, was warm in winters and cool in summers. The new architecture had done away with the thick walls and included bay windows of glass that changed it completely. It has many other variations. The shrine was reconstructed after it was destroyed in a devastating fire in 1995, after a protracted stand-off between militants led by Pakistani fighter Mast Gul Khan and the army. Most of the town was also reduced to ashes.

That is why the digitization of the shrines becomes all the more important. Dastgeer Sahab shrine like Khanqah was micro-digitized. It was easily recreated. The only change in Dastgeer Sahab shrine was that the new structure did not shift its underground base, the main plinth. JKPCC wanted to uproot it but the architects refused saying it has a traditional style of putting half brunt logs in its base that protects it from the earthquake. It was left as it was and recreated even though the tensions between the two sides led to a month-long delay.

“I traditionally go to Dastgeer Sahab as my ancestors have been going for prayers,” Ikhlaq, a resident of Lal Bazaar, said. “Though the shrine is a replica of what it earlier was, somehow, I am still not finding the same solace that I would get before it was destroyed by the fire.” He feels that when lot many people pray and meditate at a specific spot for centuries together, it adds some spiritual value to space which can be felt, not seen.

With the demographic shift, the challenges are changing. Right now, for instance, the major challenge at important shrines like Jamia Masjid, Mukhdoom Sahab, Naqshband Sahab, Hazrtabal and Dastgeer Sahab is about parking. In Dargah, for instance, Government of India agreed to fund a multi-layer parking on a four Kanal land at Hazratbal and released the money but the Wakf Board is unwilling to permit it. The reason: they want to set up a shopping complex on the same land! Even Dubar Sahib Amritsar acquired two surrounding localities to pave way for parking in recent years.

The revenue is important to Wakf because they are increasingly being compared to the Hindu shrine boards in the state which are million times billion strong. Its mandate is primarily to protect the shrines and ensure better and hassle-free access to the devotees. But the emphasis on revenue has started creating unprecedented situations.

In 2012, Beigh said he was shocked to know that the Wakf Board had given the shrine of Simnani Sahab in Kulgam, the saint very close to Amir-e-Kabeer, to a contractor against Rs 52 lakh a year. “Once he paid this sum, the contractor has the right to create and evolve his own systems to get most of it,” Beigh said. “When I visited the shrine, I saw the entire belt enlightened by light-works and decorations, mostly plastic. Even a spark would have reduced the shrine to dust in a moment. I went to Chief Minister and it was investigated and it was proved that the shrine is being given to a contractor for the last three years.”

Beigh said that people in Kashmir were using paper decorations (waw-maal) on the auspicious occasions at home and in the localities. “Now plastic is dominating the scene because it is dirt cheap,” he said. “It is deadlier than paper.”

It is not government agencies including the Wakf Board that has to get sanitized on the issues of protection of the heritage related to faith and history. Even people need to be aware of it. There are scores of shrines, some of them very old, which people are managing locally.

“Earlier, people had modest earnings and now mostly they are prosperous and they invest in new structures,” Beigh said. “In Pampore, a few years back, the government had to intervene to stop the demolition of Kashmir’s oldest mosque, outside Srinagar, as people wanted to construct a new spacious one. It barely survived and still lives, albeit in a choking situation.”

Earlier, a similar situation erupted in Qaimoh, Kulgam. The locality decided to rebuild the shrine where a mother of Sheikh Noordddin Noorani (RA) is resting. “It has been the original Sultanate era structure,” Beigh said. “But we were too late and they had destroyed the oldest structure when we tried an intervention.”