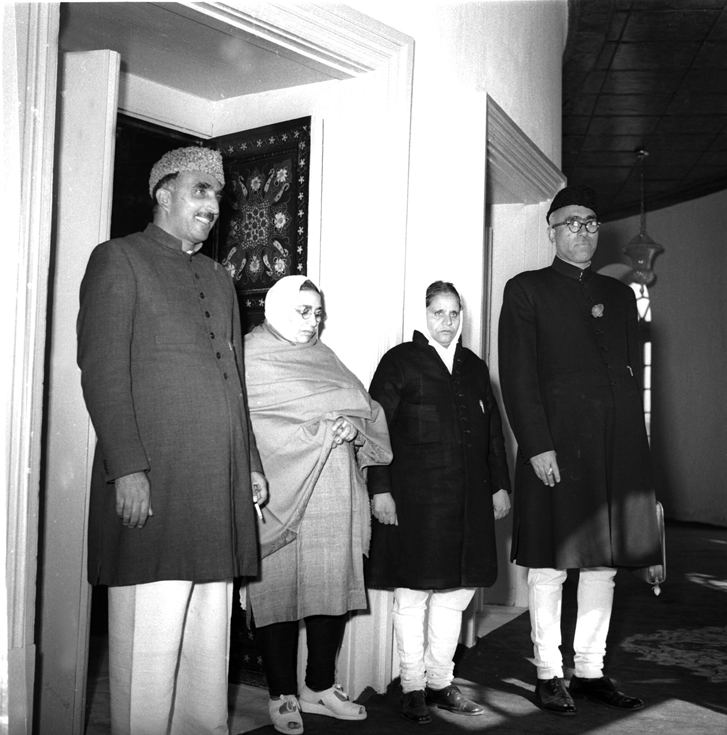

April 8, 1964 J&K state government released Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah after withdrawing the Kashmir conspiracy case. It was a major development that was written about in most of the world simply because of the partition and Kashmir dispute. On April 24, 1964 America’s main intelligence gatherer Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) drafted his profile for its use, analyzing the situation. The secret document was de-classified by the American government in December 1999. Kashmir Life publishes the document on Sheikh’s 111th birth anniversary that falls on December 5.

Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah, now 58 years old, has for 35 years been the most important figure in Kashmiri politics. He has spent nearly 13 of those years in prison and was recently released from his longest stretch, some ten and a half years. In his first moments of freedom, the Sheikh was quick to exhibit the outspokenness and the sense of Kashmiri patriotism which have been his trademarks. These qualities are the bases of his popular support and the main ingredients of his now legendary role as the Lion of Kashmir, they also account in large measure for his long incarcerations. The major dispute between India and Pakistan over possession of Kashmir and the magnitude of this issue in Indian politics will be greatly influenced by the role Abdullah plays now.

Role in Accession

Abdullah first came into the limelight internationally in 1947 and 1948 when the dispute over Kashmir between the newly independent dominions of India and Pakistan broke into fighting and then was taken to the UN Security Council. The withdrawal of the British and subsequent splitting of the subcontinent along Hindu-Muslim communal lines faces the Hindu Maharaja of predominantly Muslim Kashmir with the decision whether to accede to India or Pakistan or to take another course. In keeping with traditional Kashmiri separateness, the Maharaja chose to remain aloof from both India and Pakistan. Within two months, however, Kashmir was invaded from Pakistan and the ruler sent Abdullah to New Delhi to request Indian help. The Maharaja’s accession to India followed quickly thereafter, and Abdullah was made prime minister of a largely autonomous Indian Kashmir. Outside observers agree that a fair vote, then as now, would have reversed this accession in favour of Pakistan.

India, in keeping with its claims to secularism, made much of Abdullah’s role. The fact that a Muslim had led his Muslim majority state into the Indian union was for the Indian’s a textbook denial of the very basis on which Pakistan had been formed—the theory that South Asia’s Hindus and Muslims formed “separate nations.”

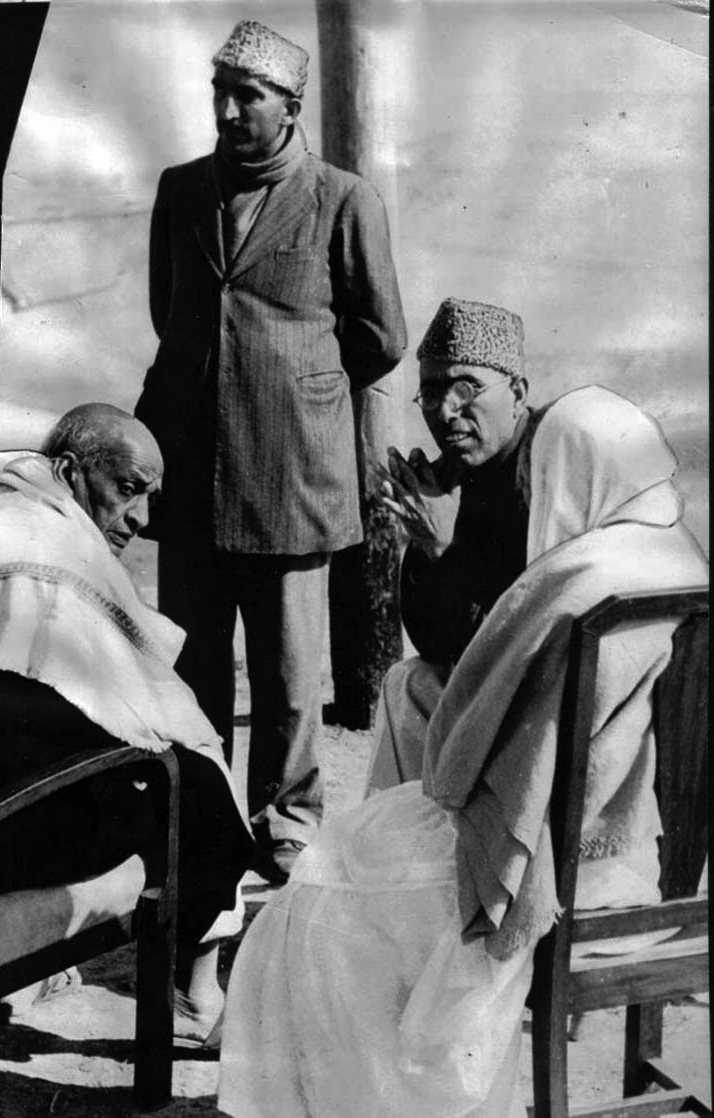

Closeness to Nehru

There can be no doubt that Nehru’s secularism appealed to Abdullah. They had long been friends and had cooperated closely during Nehru’s long struggle against the British and Abdullah’s against the Maharaja, conversely, Abdullah had never hit it off well with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the prime mover behind the creation of Pakistan. As early as 1939, Abdullah had secularized his political organization in Kashmir by admitting Hindus and Sikhs to membership and by dropping the word Muslim from the title.

Abdullah was also moved strongly by Kashmir’s feeling of separateness. Conversations with him in 1947—and more particularly with his wife and some close associates – bear out that he then favored some solution in which the state would go its own way. He seems to have agreed to accession to India out of the strength of his regard for Nehru and his fear that otherwise the state would be overrun by Pakistan.

During his early years as prime minister, the Sheikh defended the accession and in 1952 formally agreed with Nehru that Kashmir’s foreign affairs, its defense, and its communications should be in Indian hands. His friends say he did not give up the idea of an independent or quasi-independent role for Kashmir but that rather, he felt these had to be submerged out of gratitude to India for its military and economic support.

The Falling Out

In time, as Nehru continued to build a strong and centralized federal structure in New Delhi, Abdullah found himself questioning New Delhi’s policies — first privately, then in 1953 publicly. He began speaking out on the need for preserving a larger measure of autonomy in the state, and his enemies began accusing him of advocating independence. All of this culminated in August 1953 when, amid considerable public disorder in the state, Abdullah was removed from the Prime Ministry and subsequently jailed on charges of “disruptionism, corruption, nepotism, maladministration, and establishing foreign contacts of a kind dangerous to the prosperity of the state.” He was replaced by his former deputy Bakshi Ghulam Muhammad who, although weak at the time, gave every evidence of being willing to cooperate with New Delhi.

The suspicion of foreign contacts was directed mainly at Pakistan, but also at the United States which, in the heyday of anti-American feeling in India, was portrayed as encouraging Abdullah in his schemes for an autonomous or independent Kashmir which would then become a US base. That overtones of this persist in the left wing of Indian politics today can be noted in a recent speech by the still vocal former defense minister, Krishna Menon, who said an independent Kashmir would be “an American Kashmir.”

Abdullah was released from prison in 1958, but his outspokenness again ran him afoul of the authorities. He was jailed within four months and formally charged with a far-reaching conspiracy-aimed at bringing Kashmir into Pakistan. He was still on trial on this charge until the day before his latest release on 8 April of this year.

Unrest in Kashmir

Why then, with this fairly consistent record of espousing policies not acceptable to New Delhi, did the Indian Government sanction Abdullah’s release two weeks ago? The answer is not simple nor is the evidence firm.

Kashmir has in effect been rudderless since last August when Nehru forced Abdullah’s successor, Bakshi, to step down as part of the sweeping proposal then current to rejuvenate the Congress Party by bringing high-powered ministers into full-time party work. In actuality, the inclusion of Bakshi was tantamount to an admission by Nehru that Bakshi’s value in furthering Kashmir’s integration into India and in keeping the lid on continuing Kashmiri discontent with Indian rule had depreciated relative to the mounting burden of his corruption, his venality, and his police state methods. There appeared to be some intent, however vague, to move toward improving India’s image both in Kashmir and abroad by introducing a measure of liberalization into the Indo-Kashmiri relationship.

This appears to have been a major miscalculation based on a faulty reading of the extent to which Kashmiris had accepted their lot in the Indian union. Bakshi contributed to the resultant confusion by maneuvering Nehru into accepting a spine-less Bakshi puppet who proved unequal to the job. The theft of the much-revered Muslim relic in late December, the popular association of the Bakshi family with the crime, and the resultant anti-Bakshi, anti-government, and, inferentially, anti-Indian disturbances served thoroughly to discredit both Bakshi and his puppet. Meanwhile, developments elsewhere were having their effect as well.

The clamor over the relic, with its communal overtones, sparked a wave of Hindu-Muslim violence in East Pakistan and northeastern India which, while now abating, has still not yet run its course. On the international scene, Pakistan returned the dispute over Kashmir to the UN Security Council and stepped up military pressure along the UN-supervised cease-fire line in Kashmir itself. And, in New Delhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, the architect of India’s rigid policy on Kashmir, fell ill; Lal Bahadur Shastri returned to the cabinet in the role of heir apparent and began grappling with the Kashmir problem.

With Nehru’s approval, Shastri effected the retirement of Bakshi’s puppet and put Ghulam Muhammad Sadiq, Nehru’s original choice and a prominent politician with long-standing leftist connections, in the driver’s seat in Kashmir.

Further liberalization measures followed, but not fast enough for the Kashmiris, whose appetites had been whetted by the ousting of the Bakshi regime and were not satisfied with Sadiq.

Sentiment began to move toward some gesture in the direction of the still-imprisoned Abdullah, whose followers had covered themselves with glory during the relic crisis and whose popularity, even after and perhaps because of his long imprisonment, was un-denied. Sadiq appears to have seen in the release of Abdullah a situation in which he might be able to play off the remnants of the Bakshi regime against the popular Abdullah to his own benefit. Bakshi, however, moved to support Abdullah’s release, apparently in an effort to capitalize on popular sentiment and to cause a crisis serious enough to force New Delhi to turn again to his own strong arm.

India’s Gamble

In New Delhi, Shastri apparently concluded that Sadiq could not last long in the present circumstances and that events in Kashmir were moving toward an explosion which would expose the use of Indian bayonets to dominate the state. Despite strong pressure from both the right and the left for maintenance of a hard line on Kashmir, Shastri the moderate seems to have decided that Abdullah might hold the key to easing the problem.

The hope of Shastri and other moderates in New Delhi was that even if the Sheikh’s views had not mellowed in prison—and his remarks sud-sequent to his release suggest they have not—he might at least sense the changing situation in India and act reasonably to calm the situation in Kashmir just as his followers had done during the relic crisis.

In persuading Nehru to agree to Abdullah’s release, Shastri appears to have reasoned that an explosion could just as easily take place with Abdullah in prison as without, but that his release, however risky, offered a possible way out. If successful, the gamble could pay off in a stabilization of the Kashmir situation. If a failure, New Delhi would in most respects be no worse off than it would have been if the chance had not been taken.

Abdullah’s Hand

Abdullah’s actions since his release suggest that although he knows he has the strongest hand he has ever had in dealing with New Delhi, he is not yet ready to play it out. His initial remarks emphasized that his basic views have not changed. He does not believe the Kashmir question is settled—neither does New Delhi, but its public position is that the accession is final and irrevocable. Abdullah believes a Kashmir settlement must be reached by means of negotiations which take account of all parties’ interests, including those of the Kashmiris.

He has left a lot unsaid, however, and he seems intent on saying only enough to secure his political base in Kashmir and to test Indian intentions without actually pushing New Delhi far enough at this time to warrant his re-arrest. He has deferred public discussion of specific matters until he meets with Nehru in New Delhi next week and has sharply criticized those who are attempting to promote a new rift between him and Nehru, his “dearest comrade and colleague.”

Test of Indian Patience

Although much will thus depend on Abdullah’s willingness to keep his pressure on New Delhi within bounds, New Delhi requires a steady hand and the courage to play the game out. Even then, the buildup of pressures on both sides may badly restrict their room for maneuver. Kashmir is the “sacred cow” of Indian politics. Nothing produces a greater furor than the suggestion that the Indian Government is weakening its line on Kashmir. Abdullah’s release has promoted such a furor, and the leading characters, especially Shastri, are under sustained attack. To protect himself, Shastri is publicly associating Nehru with each step of the game.

A press report has already suggested that Nehru might be having second thoughts and that he has privately criticized Shastri for the “mess.” At the same time, Nehru’s public remarks have been quite mild, perhaps reflecting a rumored letter of reassurance from Abdullah. Nehru has publicly described the Sheikh’s initial remarks as “unfortunate” but has also alluded to the possibility of press exaggeration.

Nonetheless, Nehru has shown himself capable of unpleasant decisions regarding the Sheikh, and he is also noted —even in the best of health— for his lack of follow-through on risky projects once the clamour reaches a certain decibel level. If the gamble is to pay off he will probably have to go beyond merely tolerating the Sheikh’s remarks and avoiding his re-imprisonment. He and his government will have to come forward with enough flexibility in their policies toward and in Kashmir to meet Abdullah’s as yet unspecified minimum requirements and to persuade the Sheikh that he has good reason to stay out of the comfortable confinement he has just left.

The possibility of a new approach to the international— Indo-Pakistani—aspects of the Kashmir problem will rest on the success these leaders have in working out a new relationship between New Delhi and the Kashmir state government.