Mass uprising coincided with the militant upsurge in 1990. It resurged after Gawkadal massacre thus paving way for twin massacres on March 1, when more than a million people marched on Srinagar streets. Saima Bhat revisits the era only to find that one incident is missing in police records and another lost in systemic deep-freeze

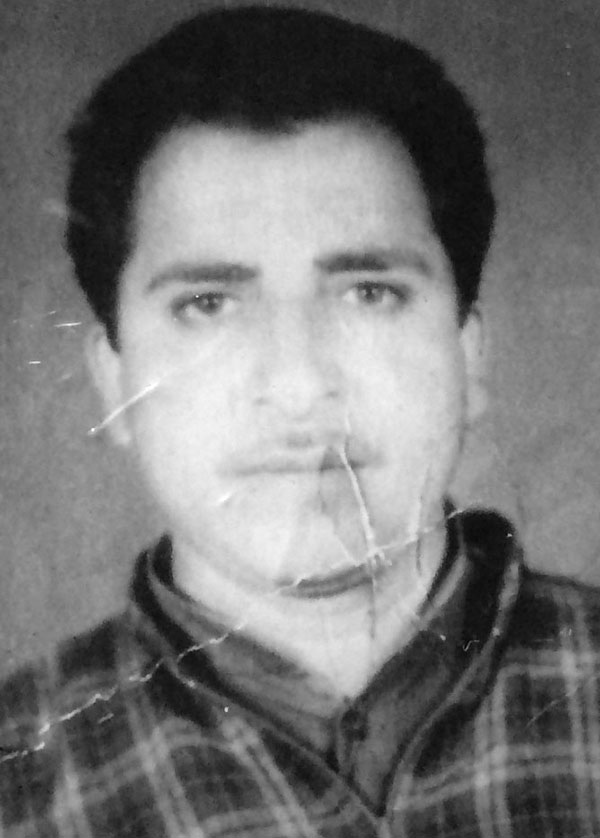

Every March, on day one, contractor Mehraj-ud-Din, 38, feels pain in his motionless right arm. He caresses his bullet-deformed belly and neck, before setting out. “I don’t want to be dependent on anyone,” says Mehraj. “Moving out and work keeps me going.”

“It was raining that day,” he vividly remembers, that March 1 morning of 1990. Then, Mehraj was 12. Situation had changed but he was unconcerned or may be too young to understand. Rumours about a ‘million march’ to the UNMOGIP in Srinagar had drawn hoards of people out of their homes in Theed, his native village near Harwan, early morning. “My cousins, brothers, my father and grandmother were out and I also joined, out of excitement,” Mehraj remembers. “It was one of the biggest processions I have ever witnessed.”

Minor Mehraj was not alone. Mohammad Ismail Bhat, a farmer from Mukhti Bagh locality, in his late thirties, also joined the procession. Sole bread earner for his family of four – three sons and wife, Bhat joined the procession despite Azi’s, his wife of 11 years, pleas. “I pleaded aggressively with him, trying to change his mind,” a distraught Azi remembers. “But he did not.”

By 7 am, the procession left for Hazratbal. As the march started, it swelled every minute. Led by a group of Kafanposh (people wearing funeral shrouds), they carried green flags with Qur’anic verses written on them. Near Zakura Chowk, another procession, albeit smaller, joined them. They had come from Burzuhama, a small hamlet on Srinagar fringes, famed for its archival finds of Guphkral era. Among them was Manzoor Bhat, 18, who had joined his father at a government nursery as daily wager, after his matriculation. The air was reverberating with Azaadi slogans.

Suddenly, three army vehicles appeared, heading straight towards the procession. Reportedly, two cops Abdul Rehman (belt No 1497/s) and Abdul Rehman (belt No 863/s), posted in the Chowk, approached the army suggesting them to change their route as a large procession was on way. They refused.

“It was going on peacefully till the army vehicles came,” recalls Mehraj.

Kashmir Bleeds, a report about happenings in Kashmir by Delhi based Kashmir Committee issued in December 1990 has quoted witnesses saying that a few soldiers came down from one of the vehicles and snatched a flag from a protestor. “This angered the protestors, as the flag had Qur’anic verses written on it. They trampled upon the flag,” says Mehraj.

Manzoor was in front of the procession and reacted to ‘desecration’. “They had shot two bullets at him from close range,” his father Mohammad Maqbool Bhat, was later told by his friends. “He died on the spot.”

Before people could react, soldiers fired indiscriminately from their vehicles. “There was chaos all over,” recalls Mehraj, who was hit by a bullet in his rib-cage. “They fired around hundred bullets in a few minutes, all directly aimed at people.” Bleeding, Mehraj ran away and hid behind a newly constructed house. “The next time I opened my eyes, I was in an overcrowded hospital room with people wailing around me.”

Then, Zakura had quite a few houses. There were just two shops, serving mostly to the workers at industrial area nearby. One was owned by Hassan (name changed), then in his early thirties.

“They fired to kill,” recalls Hassan, who witnessed the massacre from his shop. “They were aiming at people.”

After army left, those hiding returned. “We got a truck from a poultry farm nearby to ferry injured and dead in it to SKIMS,” says Hassan, who fainted after picking up seven corpses. “They were mostly young, shot in their heads. Their brain had come out, which I later collected and buried in an open field adjacent to my shop.”

Later, Hassan came to know that 14 people were killed and over 50 seriously injured. The slain included Azi’s husband Bhat, and Manzoor. Both died on the spot. That was around 2:30 pm.

Gardner Maqbool, Manzoor’s father, was posted near Zakura, barely half a km away. Gunshots attracted him and his three colleagues to the Chowk. “As we reached near the Chowk, soldiers wearing turbans shot at us but we saved ourselves by hiding behind a government hut,” recalls Maqbool. “We came out when they left.”

Maqbool started helping injured. After half-an-hour, Maqbool’s friend came and drove him in their car. “Without telling anything, he drove me straight to SKIMS,” says Maqbool, as he breaks down. “Manzoor was lying on the floor among the dead.” He collapsed and for four days he went blind.

Manzoor’s was the first coffin coming out of sleepy Burzuhama. “He is the first martyr from our village,” says Maqbool with a hint of pride in his voice.

Unaware of Zakura happenings, Srinagar was busily crowded. Tens of thousands of people had come from across Kashmir, joined in a huge crowd in Eidgah and marching through Lal Chowk and submitted memorandum to the UNMOGIP in Sonawar. Azaadi apart, most of these memorandums protested against the wholesale massacres that governor Jagmohan’s government had resorted to in Gawkadal, Alamgiri Bazar and Handwara.

The processions would reach UNMOGIP, handover the memorandum and return. Seemingly, Azaadi was round the corner. The only people who would have the honours of handing over the memoranda would be the Kafanposh.

By then, Tehreek-e-Hurriyat Kashmir, a joint alliance of 13 like-minded organisations had been constituted. JKLF was not part of it, remembers lawyer Mian Abdul Qayoom, who was the main face of the conglomerate.

But to project the alliance as a united face of Kashmir, they lacked JKLF support. “I met Ishfaq Wani and he promised that he’ll talk to us once he is back from his Pakistan visit but unfortunately he was killed before that,” says Qayoom.

Ali Mohammad Dar, now 82, drove big bus JK 2 Q – 1591. With people stuffed in and over it, this Batamaloo resident, was on his way to Raithan (Budgam). With all roads clogged with buses, he took bypass route from Batamaloo yard to come out of the city. As he reached Tengpora bypass, soldiers blocked his way by putting three vehicles in front of his bus. There were no escapes.

“They first snatched my keys and then, started firing indiscriminately towards the bus top,” Dar remembers. “Everybody was running for his life but a woman and her kid, who were in my bus, were pleading soldiers not to fire but they didn’t listen.”

Amid firing, bus emptied. Dar remembers the woman and her kid and another male as the last passengers still in his bus. He also remembers a cop driving from Hyderpora in a gypsy but fleeing as he saw the happenings.

Then, Dar remembers, soldiers summoned the man down. “He was pleading me to save him,” Dar said, “Soldiers could have killed him either way but they speared him, returned me keys and left.”

Frozen in his seat, when Dar came down, he was shocked. “I had not seen any dead on my right but when I moved towards the left of my bus, I saw piles of bodies.” Apparently, the people who were jumping out of the bus were getting bullets.

Army left and CRPF men appeared on the scene. Manning a bunker, they commanded Dar: “First shift all corpses into your bus and then wash the blood drenched road.”

Dar counted “22 bodies”. Then, he switched the engines on and drove the ‘bus of the dead’ to Bones and Joints Hospital in Barzulla.

Crowds turned mad in the hospital premises. They wrapped the bus in black cloth and pushed it inch-by-inch to Raik-e-Chowk Batamaloo, near Dar’s residence. This might have been the only big-bus ever that was pushed by man-power for a long distance without any mishap simply because it carried corpses. Barzulla proved Dar’s last stop. Now a cardiac patient, he gave up driving the same day. The bus remained untouched for a long time. Bloody, with so many killed in it, people considered it haunting, possessed. Then a driver was hired and eventually it was sold as scrap.

Gravedigger Abdul Kabir Sheikh says that day he buried at least 15 corpses in Batamaloo. Later, some were taken exhumed by families for reburials in their respective villages.

Epithets speak in Magarmal Bagh: Abdul Rashid Dobi (Ichgam), Abdul Razak Dar (Naru Ichgam), Abdul Aziz Kutey (Kreimshier), Ghulam Hassan, Ghulam Mohammad Rather and Ghulam Ahmad Tildoz (Budgam).

Kreimshier resident, Rouf Ahmad Mir, 40, was a part of procession. Then 14, he was in the same bus. Mir was part of a huge crowd that Budgam had contributed to the ‘million march’ in reaction to a rumour – ‘Budgam does not need Azaadi so it does not care about processions’!

Crowds started assembling in Budgam at 8:30 am – thousands came, from villages on foot and in buses. Throughout this journey, people would serve them with Tehri (fried rice), fruit and milky water. While walking, people were singing slogans of freedom, carrying green flags with some Kafanposh. Mir was not alone. His father, cousins, uncles, and many other family members were part of the procession.

They reached UNMOGIP at around 2:30 pm. “Only few Kafanposh were allowed to enter and rest of us, were asked to return,” Mir remembers. “No buses were available so he trekked the distance up to Batmaloo bus yard.” Here, he boarded bus and found some space on its roof.

“Everybody was shouting Azaadi slogans and once the bus took the curve and came on main bypass, soldiers stopped us and asked to raise our hands,” Mir said with that boyish grin. “One of them snatched keys from driver and another soldier fired a few shots in air and then pointed towards the bus roof. Unaware how to save the skin, some of us raised their pheran to prevent themselves from bullets! Many jumped out, a few were lying down.”

Mir also jumped from the roof and took refuge under the bus. “I saw soldiers finding those alive after hit by bullets and then firing upon them again,” Mir said. “Some passengers finding bullets flying around tried to get back into the bus but those hiding inside had bolted it from inside.” As the struggle to reopen the doors was on, Mir says bullets sprayed. “Seven persons were killed outside the two doors,” he remembers.

Soon after, a few cops reached and soldiers got cautious. Another Kriemshair survivor, Ajaz Ahmad, then 14, remembers those cops saying: “save these dead by shifting them into the bus, otherwise soldiers will burn them down.” Mir remembers his father having blood dripping from his temple bone joining the operation to ‘save’ corpses of co-passengers.

Once the “operation” was over, these boys were asked to save their skin and they “jumped into the water of flood channel”. They returned after soldiers left. Some left in the bus to the hospital and many took refuge with residents, who opened their doors for them.

Within hours, curfew was re-imposed. Mir and Ajaz managed reaching home next day, at 3 am. Some reported back home after two days. One of Mir’s neighbour returned after 18 days as curfew remained imposed for 17 days. By then, his family had mourned his “death”.

The incident changed Kriemshair. Angry, Mir was desperate to pick up the gun but returned home from Kupwara. “But militancy started after that incident for our locality,” he said.

“There is no investigation file related to Tengpora incident,” a middle rung police officer in Srinagar’s SSP office said after scanning the records. “I guess you have been misinformed. No such incident has happened.” And no FIR was found.

Unlike Tengpora, there is a police record in case of Zakura massacre. Accessed by this reporter, FIR number 38/1990 registered under section 188, 302 RPC reveals 11 people as dead and 13 injured.” It further writes that “section 144 was imposed and incident happened as the restriction was defied.”

Investigation was carried out by two ASI rank officials: Ghulam Mohammad Khan and Abdul Khaliq, both ASI rank officers. They had submitted a 3-pager, two listing the names of the dead. “People were carrying green flags, shouting slogans and they had defied curfew,” third page reveals. Status: investigation was closed because, “crime has happened but eye witnesses couldn’t identify the accused.”

The then Governor Jagmohan briefly mentions March 1, in his autobiography, My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir, “Up to March 1, things moved not very differently from what I expected, except that JKLF blatantly misused the facilities provided for the religious festivals and organised a very large number of processions to the office of the United Nations Observation Group,” he wrote. “From these processions and related activities, however, it was evident that the Jama’at-e-Islami, Hizb-ul-Mujajideen and other pro-Pakistani organisations were being relegated to the secondary and even insignificant positions. Obviously, this was not to the liking of these organisations. Most probably, it was they, who directly or indirectly, caused these two serious incidents on March 1, 1990.”

“Following widespread protests against the killing at Tengpura the army conducted an inquiry into the incident on directions from the government. The report of inquiry sought to justify the killings on the ground that the people had pelted stones at an army vehicle carrying school children of military personnel,” records India’s Kashmir War, another report by Kashmir Committee. Lt Gen M A Zaki was the enquiry officer. “J&K government had issued an order on February 20 asking schools, colleges and other educational institutions to remain closed till March 15.”

Seemingly, the twin incidents were aimed to work as a closure of the mass uprising that had re-erupted after the series of Gawkadal massacre. After the twin massacres and later on May 21, processions stopped. People were seen on streets only in 2008, almost 18 years later.

For families who lost their bread-winners, seeking justice was never an option. Kashmir changed quite faster after these twin events.

Ompora’s Manzoor Ahmad Dar, Narkura’s Abdul Qayoom and Abdul Majeed Sofi were also killed in the same bus. Unlike Manzoor and Qayoom, Majeed left behind his 23-years-old wife Shameema with two minor daughters, one was 2 years old and another only six months old.

Baker, Majeed was a daily wager in Irrigation department and living with his family in a single room. His widow Shameema was adjusted by the government. She closed the family bakery shop and converted it into a small provisional store. She would keep herself busy with needle work.

“This is how I managed to run my house and send my daughters to school.” Shameema says. But she could help her daughter graduate. Almost eight years back, she had a cardiac problem and her daughters gave up studies.

Shameema was lucky, if compared to Theed’s Azi. “I couldn’t see his face one last time because he was taken directly to the graveyard for burial,” says Azi, now in her late fifties, surviving on anti-depressants since then. Frustrated, she had gone into seclusion for a very long time, leaving her three kids at the mercy of her relatives. “She is not in her senses after the death of her husband,” informs a neighbour.

But it was not Azi alone. Shakeel, her eldest son, who was then a 4-year old toddler, grew up a depressed adult. “He roams on streets in tattered clothes seeking cigarettes from passers-by,” the neighbour added. “This family is destroyed.”