With ferocious Jhelum inundating the habitations on its banks, displacing populations and destroying properties, thousands of people trekked to the foothills housing the shrine Makhdoom Sahab in Shehr-e-Khas. From the most revered shrine, they were watching the town gradually disappearing in the water. Bilal Handoo spent a day with the crying crowds to tell a harrowing story of pain and loss

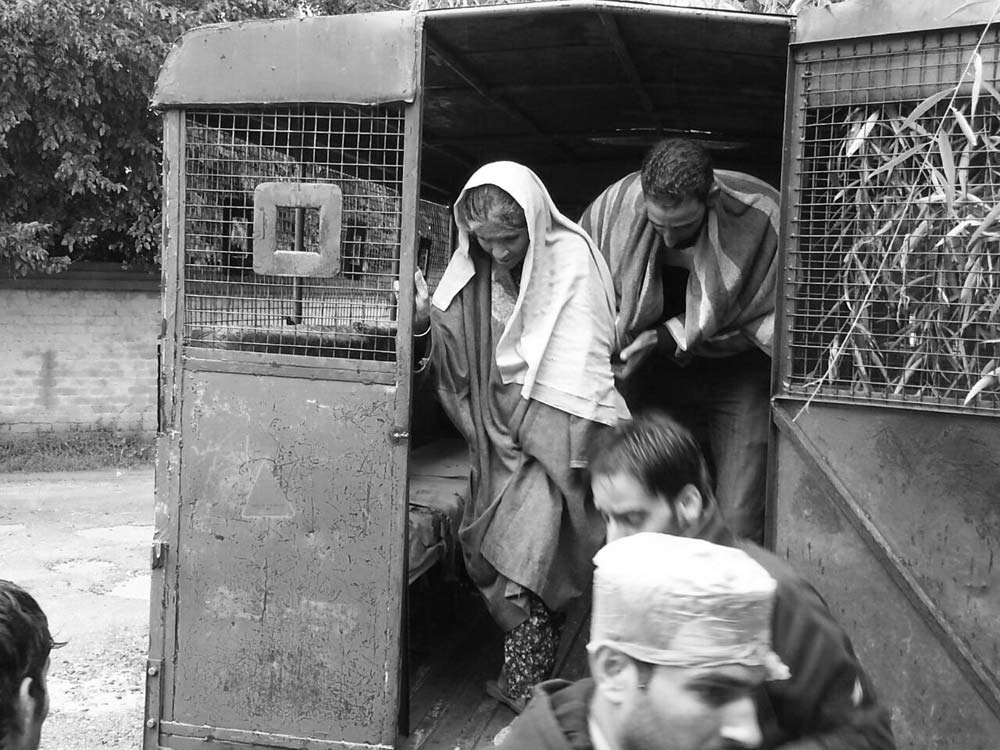

Another truckload of men, women and children has arrived. All of them look haunted. They have just reached a place which is crowded, noisy and tearful. People are going uphill by climbing a marathon stairway leading to the shrine. Many sitting on stairs are busy discussing the threatening situation prevailing presently over Srinagar. This is the Makhdoom Sahib Shrine of Old Srinagar. And since Sunday, September 7, the shrine has turned into a refuge centre for hundreds of flood-affected people of the city.

Another truckload of men, women and children has arrived. All of them look haunted. They have just reached a place which is crowded, noisy and tearful. People are going uphill by climbing a marathon stairway leading to the shrine. Many sitting on stairs are busy discussing the threatening situation prevailing presently over Srinagar. This is the Makhdoom Sahib Shrine of Old Srinagar. And since Sunday, September 7, the shrine has turned into a refuge centre for hundreds of flood-affected people of the city.

It is Thursday. Four days have passed since the worst floods rendered thousands homeless in Shehr-e-Kashmir, the capital of the valley for more than 1000 years. Most of the displaced are living with their relatives in dry patches of the city, mostly in the ‘old’ city.

But a great chunk of people hailing from uptown has taken refuge inside this hill shrine. And the rush of flood-ravaged people is only building at the place.

People packed inside the shrine wear parched faces, dark-circled eyes and anxious moods. It seems their anchor of hope has been lost somewhere in the devastating flood. Their houses, shops and lands; everything is inundated.

Among the crowd, a young lady, probably in her late twenties, is crying like a child. She is being comforted by five of her family members. “Come on, you are my brave girl,” an old lady is telling her. “It is just a matter of time, we will be back home. Now, enough of this crying; stop it now! You will fall ill…I am promising you that we will be soon at home.” But there seems no end to her crying in the crowded shrine where perhaps tears are falling like never before.

There is this old man sitting near the men’s washroom at the shrine who seems lost in his own thoughts. For the past four days, Mohidin Bhat, 66, a retired bank clerk is in the shrine with his family of eight members. It was Sunday when the water level of Dal Lake unnerved locals. Till afternoon that day remembers Bhat, the water level crossed the bund and started spilling in the area. By the evening, the flood had submerged lanes, alleys and streets, triggering panic.

Bhat shifted his belongings to the second floor of his home. By that time, his neighbourhood was deserted. Everybody had fled. Bhat waited for a while, thinking the water level might not surge beyond the limit. But at midnight when the deluge showed up at his doorsteps, he had to flee with his family. “It was almost a blackout in the area,” Bhat recalls the horror of the night. “A non-stop downpour had already cut off electricity. But we walked and walked till we reach at the shrine which we thought only a safe place for ourselves.”

Falling silent intermittently, Bhat lifts his eyes towards three girls sitting inside an opposite park. Almost everyone, like these girls, looks drowsy and drained.

And meanwhile, a thunderous sound of a chopper hovering overhead ends the trance of the shrine refugees. Everyone lifts and tilts their heads towards it. Some boys on spot are booing at the flying machine in rage. “Last day,” says Bhat, looking towards the chopper, “one of the choppers dropped some bags of flour and packets of biscuit. But all of the dropped food packets were expired. Huh, they are on a rescue mission! I know, they must be gloating loud over the fact that they rescued and provided relief to us. But see, by feeding us the expired food, what should one conclude out of their intentions.” He does not know the relief being dropped is by debit to state government and army choppers are just a carrier and a courier.

After a while, Bhat walks away, sighing and mumbling. No sooner than he merges with the crowd, somebody starts announcing from the public addressing system of the shrine: “Please assemble in the park opposite the fountain and have your lunch.”

The announcement set off motion in an otherwise weary crowd. One can see the awkward body language of these people while queuing up. Most of them are avoiding eye contact with passers-by. Perhaps, they don’t want to cut a victim image for themselves. After receiving their lunch, they are slowly walking into the park, their heads lowered.

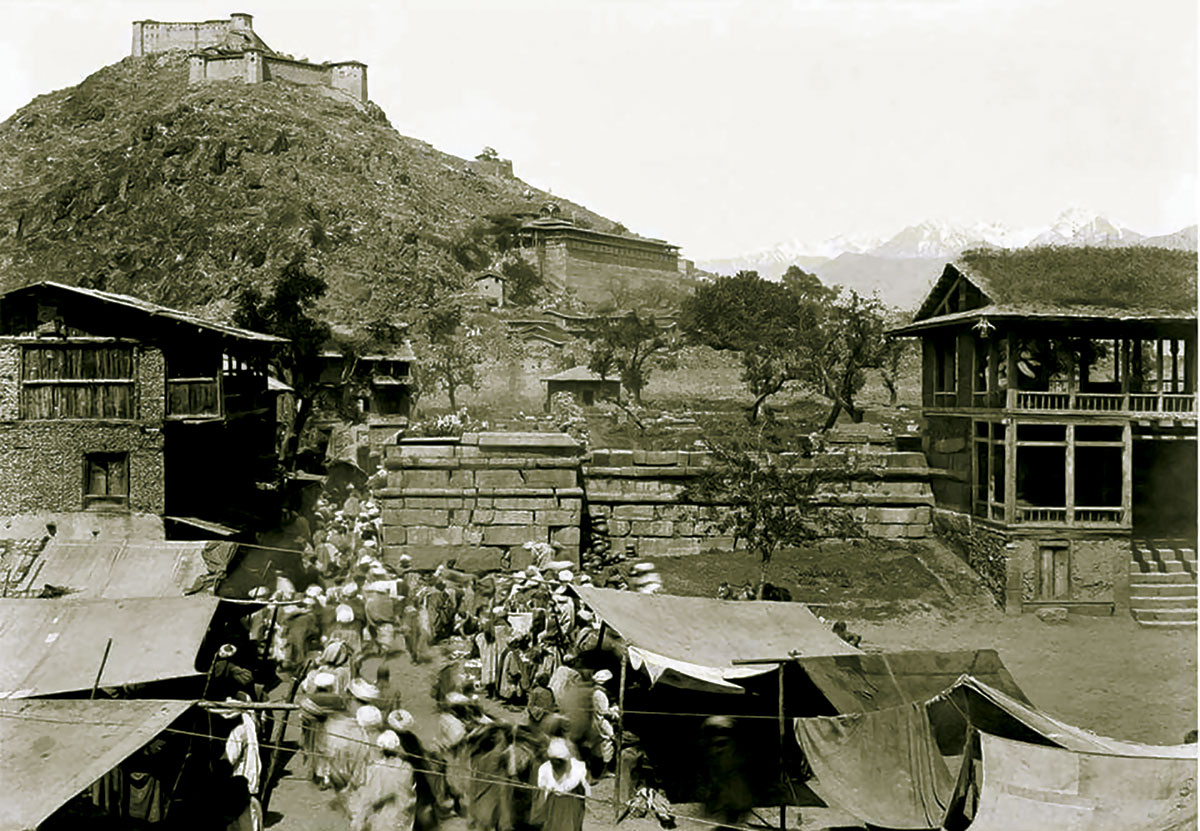

At the corner of the park, one middle-aged man is looking outside at the view of the entire Srinagar visible from the spot. In front of his eyes lay the city crowded with households. Mainly rusty rooftops are visible. There seems no trace of life amid spilt water around.

On his left side, three men are discussing their flood-doomed fortunes. “I am completely ruined,” rues a man with salt-and-pepper hair. “My garment shop at Sonwar got completely submerged. I had invested everything in it, but now…” Well before he resumes, another man begins: “My car was washed away by the flood. My house at Bemina is deep-neck in water…but anyways, I am grateful that I and my family are alive.”

Such conversations are going on everywhere in the shrine: under Chinar trees, on the fence, inside parks and in the praying spaces. Some break down while talking. Others put up brave faces while recounting their share of losses. Most attribute their fate to the wrath of the Almighty. But by talking their heart out in the trying times is seemingly keeping these flood-displaced people busy at the shrine.

Scenes at Kastoor Pendh, a park from which major parts of Srinagar are visible, are quite intriguing. Many people from downtown have walked up here with their cellphones. At the elevation, their ‘betraying’ networks seem to catch up. With each passing minute, the cellphone crowd is only surging. But not everyone is lucky to hear that ‘much-needed’ bell at the receiving end. The crowd is not entirely local. There are migrant workers, trapped tourists and puzzled foreigners. Each one of them is desperate to talk.

Some of those whose calls are being answered are literally crying their heart out. “Tell Mummy, I am fine,” a boy from Sopore is assuring someone on phone. “Everything is lost,” cries a lady sitting on the fence. “What is news from your side?” “Look, Khurshid is missing since Saturday. He had gone to visit his aunt at Jawahar Nagar. Somebody please go and rescues him,” pleads an elder with someone on phone. Those who are managing to call their relatives only add to the amount of pain otherwise palpable at the place.

Around dusk, another announcement is aired. It is the call for what appears as early dinner. They again fall in line. This time around their body language appears less unnerved than earlier today. Perhaps the darkness which has descended over them has ebbed out some of their fears. And meanwhile, another truckload has arrived.