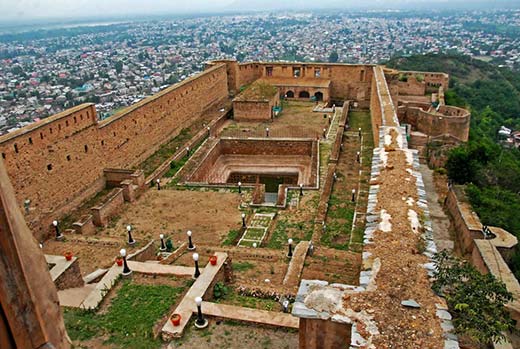

Sitting atop Koh-i-Maran hill a 200 year old military fort is witness to Kashmir’s changing political fortunes. Safwat Zargar takes a walk around the fort after it was thrown open for public after 24 years of occupation

Pic: Bilal Bahadur

If there is any illustration of “too close but too far”, Koh-i-Maran Fort for Kashmiris, in the centre of Shahr-e-Khaas (Downtown) till June 28, was the best example. While the life of common people in downtown revolved around the fort, it remained occupied by paramilitary forces for 24 years, serving as a picture to eyes but sting to the heart. The structure manned by personnel of Border Security Force (BSF) for decades lived with desolation and barbed wires, and silently witnessed the dance of death on the streets of Srinagar – metaphorically abiding – what every Kashmiri had to, over the two decades of violence.

Visiting the fort atop Koh-i-Maran hill, also known as Hari Parbat or Predemna Peet was a dream for Kashmiris, as the forces had shut it for the public after the armed resistance started in 1989. But after June 28, it seems that Kashmiris can enlarge their enjoyment of the historical legacy it has been part of it.

“I always yearned for having an insider’s look of the fort, but I couldn’t,” says Arif Shafi, a youth from Hawal, who was born in early 1990s. “Though I haven’t gone there since it was thrown open but I will surely do in coming days.”

First, it was Mughal emperor Akbar, who ordered the construction of walls around the hill in 1590, four years after the Mughal rule of Kashmir valley began.

“The plan was to create a new capital city around the Koh-i-Maran hill and that is why Akbar created a 3.5 mile long and 10 metre high wall known as Kalai,” says noted poet and historian, Zareef Ahmad Zareef. The wall, which came up at the cost of one crore and ten lakh of that period, was finalized during Shah Jahan’s rule and took almost 19 years to complete. However the hill top was without any structure or fort during the Mughal rule.

“The city was called Nagar Nagar and it housed the courtiers of Mughals, soldiers and other officials of the kingdom. It even had a hospital,” Zareef says.

Almost three centuries later, the Afghan governor, Atta Mohammad Khan built the fort – Koh-i-Maran Fort –for Afghan soldiers in 1808. Carved out in the style of Central Asian architecture, the fort – only in the valley – served as one of the biggest bunkers of Afghan army, says Zareef. With four huge towers, the fort is spread over 60 kanals of land and used to house 750 soldiers at a time. The fort had three ponds constructed inside it from where Afghan soldiers used to consume water. “Afghans also built a mosque in the fort, which stands till now,” he says.

On the other hand, Dr Sheikh Showkat Hussain, who teaches Law at Central University of Kashmir, says: “The claims of historians that the fort was built for surveillance purposes by Afghans are absurd. The first constructions by Akbar were to ensure livelihood for the locals who were largely persecuted by the Chaks. The idea was of ‘work for food’ for Kashmiris, who had stayed back, after facing ruthless oppression of Chaks.”

Whatever the case, the hill couldn’t hide the identity of Kashmiri hospitality and culture. On the western slope of the hill is the famous Shakti Temple, highly revered by Kashmiri Pandits who used to flock the place on Mahanavratri and during annual Amarnath yatra. The hill is dotted by shrine of Khwaja Makhdoom Sahib (RA) and the stone mosque of Akhund Mullah Shah on the southern slope symbolizing the syncretism of Kashmiri culture. On the southern side of the outer wall there is a Gurudwara, famously known as Chatti Padshahi, which commemorates the visit of Guru Hargobind Sahib Ji. During the Sikh rule, a Gurudwara was constructed inside the fort, according to Zareef.

With the signing of Treaty of Amritsar in 1846, the fort went to the administration of Dogra rulers who also used it for military purposes. In 1858, Maharaja Ranjit Singh built a temple inside the fort.

According to the former director general tourism and state convener of Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) Muhammad Saleem Beg, the fort throughout its life, was used for two purposes; to prevent attack and for the surveillance of the activities of the population. “But it was Dogras who shifted the approach from centralised control to the physical presence of forces deep into the population,” he says.

Dogras shifted their military base from the fort to Badami Bagh, says Beg. “After 1947, the fort was a state protected heritage site,” he says.

According to Sheikh Showkat, all these stories are concocted and it is the Indian historiography which has maligned Mughal and Afghan rule of Kashmir. “Koh-i-Maran Fort was a symbol of an independent kingdom headed by Shuja Shah Durrani,” he says. “It was Afghans who issued currency coins in the name of Sheikh Ul Alam (RA) or better known as Alamdar-e-Kashmir, and that thing is very important to understand their (Afghans) relationship with the people of Kashmir.”

For Zareef, the fort was always used by different rulers to showcase their might. “Even Sheikh Abdullah used it for his political pursuits. He even hoisted a flag of National Conference on it – a sign of the ruler who was in the power during a particular period of time.”

While the valley underwent tumultuous political changes and ascendance of different rulers, the fort also became a victim. Fearing that armed fighters may take this elevated position to carry attacks on security forces, BSF occupied the fort in 1990.

The fort was thrown open for a brief period in 2007 but soon a controversy surrounded it and the government had to close it down. Zareef says, “it was because forces deployed in the fort had turned the old mosque into a latrine and it was only after the interventions of civil society and locals that Archaeological Department of India ordered the restoration and rebuilding of the fort.”

“The fort symbolizes the tyranny and onslaught Kashmiri have faced over the centuries from different rulers,” Zareef says. “There is no better example of Kashmir than this.”

Since last month, a good number of people, mostly locals, have visited the fort; however, Arif from Hawal, complains that one has to travel to Tourism department at Polo View to get a pass.

While acknowledging that there is no ticket counter at Koh-i-Maran as of now, Director Tourism, Talat Parvaiz says that they don’t want more and more people going uphill. “We have kept the maximum number of visitors 100 daily and in addition to that we have to inform the security men 24 hours in advance about the passes issued to the people,” he says.

According to Zareef, Afghans had dug two caves (goaphs) on the eastern and western side of the hill – Kathi Darwaza side and Islamia College side – to escape, in case of an attack. While the cave on the side of Kathi Darwaza also known as peer goaph was blasted by Indian army during the 1965 Indo-Pak war, the other cave is being renovated.

The fort is also famous for two blasts or toaphss, fired each day, signalling the dawn and lunch time during the Dogra period (1846-1947). “One toaph used to be fired at 4 AM in the morning and another at 12 PM in the day,” Zareef says.

Tourism department has different plans in pipeline to turn the fort into a tourist destination, says Parvaiz. “The site has been conserved and different viewpoints have been created to allow people have a panoramic view of the Srinagar city,” he says. Parvaiz further adds that the walls and floors inside the fort have been already repaired and ponds inside the fort have been cleaned up and restored.

The department has also repaired the road leading to the fort and a restaurant of tourist department has already been set up. “The fort will also have a light and music station by the end of this year,” says Parvaiz.

Nice article