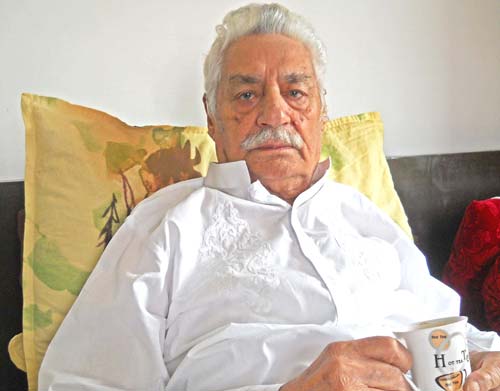

At 95, Agha Nasir Ali, a flamboyant civil servant who was known for his dressing sense and decision making powers spends his days reminiscing the golden moments of his life. Bilal Handoo spends some moments with Agha to profile his illustrious life and career.

There is an apparent stillness inside Agha house in Srinagar’s Rajbagh area. Three dogs are patrolling in the lawn. An old man is busy cutting grass at the far end of the garden. As I stepped inside the house after making sure that the barking creatures are away, photos of bygone times, placed tactically on tables in the drawing-room, catch the sight.

In one of the rooms, Agha Nasir Ali, 95, the erstwhile secretary to government of India is quietly laying on bed. His face lit when he saw me coming in. With a smile spread across his face he shook my hand and offered me a seat next to the bed.

Next to his bed was a small table on which a framed picture of Agha with his second wife was placed among colorful strips of medicine. He lives here with his second wife, Shaheen Agha and son Ali, who studies in Class 9.

The man in his mid-nineties is spending his time on bed now. Two years ago, his health complexities compounded to such an extent that his body movement got badly hampered.

But his physical frailty has not erased his token stern looks from his face, which he carried as district commissioner (DC) of Kashmir and Jammu regions.

“People were scared of me,” he quipped. He paused and then continued: “As an official, I acted tough. I never allowed unruly elements to toy with the law and order situation of state.”

In one such incident post 1947, when Maharaja Hari Singh and his durbar had left the valley, his son Karan Singh was once leading a procession against state government, organized by Jammu based Praja Parishad party on the outskirts of Jammu. Agha, then DC Jammu reached at the spot, parked his jeep in the middle of road and in a commanding voice ordered people to retreat. “I have imposed section 144 here, so you can’t carry on this procession here,” he warned them.

Agha’s stern warning soon had its effect on procession that dispersed without creating any scene. Later that day, Agha met Karan Singh at his palatial house in Jammu and told him: “Did you seek my permission before leading a procession? When your father was ruling this state as Maharaja, he used to first seek permission from Wazir-i-Wazarat (now known as deputy commissioner) and then only he would move out.”

Agha told Karan Singh that you are just a nominated head (Sadr-i-Riyasat) of the state and you should have first sought my permission before marching ahead with the procession. “He reprimanded his officer Mohar Singh for not seeking prior permission for procession,” Agha recalls.

As he shares past events of his life, he unwittingly cracks jokes that fill the room with laughter, where an apparent forsaken ambiance is palpable. “His sense of humour is too good,” his wife Shaheen said.

After Shaheen left the room, Agha with great efforts started to talk about his life again.

He still remembers how he played an instrumental role to kick start civil services in Jammu and Kashmir. It was late 1930’s and state of affairs across sub-continent was changing at a very brisk pace. During the same time, Agha Nasir, then a young man, had just completed his Bachelor’s degree in Arts from J&K’s oldest institution, SP College (established in 1905). Somehow he came to know that Maharaja Hari Singh has nominated his finance minister Thakur Kartar’s son Singh to England for civil services training and on his return he would be inducted as an official in Dogra administration. “During Dogra rule, Maharaja used to nominate individuals for training in civil services in England,” Agha says.

As Agha heard about the nomination of Thakur’s son for civil service training, he approached Gopalaswamy Iyengar, the then Dogra Prime Minister of J&K and told him that if serving in Maharaja’s cabinet fetches one chance for nomination, then he too should be send to England for the civil service training, as his grandfather was also minister in Dogra regime. Agha told Iyengar that his Muslim identity shouldn’t mar his chance. This started, what Agha calls, a verbal duel between the two.

“When will all these distinctions disappear,” Iyengar told him. “That will be the salvation of India, but so long as these considerations will prevail, I have no other alternative but to press for my claim,” Agha replied.

“How about, if we throw all these jobs to competition,” Iyengar proposed. “That will be too ideal sir,” Agha replied. “Then go and wait,” Iyengar told Agha.

For the next two years, Agha kept on pressing for his demand to end nomination system in the state and start Kashmir Civil Services (KCS). Maharaja took his time to take a decision on the matter and meanwhile, Agha left for Aligarh to pursue his MA LLB.

And then, one day when he was in Lahore to spend his winter vacations, a letter from Jammu reached at his address in present day Pakistan. The letter was from Iyengar and it read: “I had proposed you once to throw these jobs to competition, so I am happy to let you know that I have started KCS. I have sent you syllabus of exam, so prepare for the exam.” For the next few months, Agha prepared for the exam.

The year was 1941 and Agha proved his inclination for administration by topping the first KCS exam held in state. He became the first civil servant from state who secured bureaucratic post through competition, rather than nomination. His first posting was as a Tehsildar with a monthly allowance of Rs 250. After Tehsildar, he was appointed as Wazir-i-Wazarat in Hari Singh’s regime.

But as state witnessed downfall of Dogra rule in 1947, nomenclature of official postings got changed and with that, state services were amalgamated with central services. He was given IAS rank and was appointed as district commissioner in Shiekh Abdullah’s regime in the state. Later, when Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad reigned over J&K, Agha was called from New Delhi, where he was serving as commissioner in central government. “I went back to Delhi very soon, where subsequently I attained my superannuation from services,” he says. In between, he also rendered his services as secretary to Government of India.

When Bakshi was ruling the state, Agha recalls, he once ordered to shoot at demonstrators in Srinagar. “Bakshi feared that situation was slipping from his hands,” he says. “I was directed to issue shooting orders at protestors, but I had my way to deal with the crowd.”

On that day, he had kept his resignation letter in his pocket thinking that he would submit it to Bakshi, in case he insisted him to issue shooting orders. But the way Agha handled the crisis, the whole situation was brought under control without leading to any law and order problem.

Agha took to stage meant for demonstrators at a place he barely remembers now, and addressed people in a sensible tone. His speech had a great effect on demonstrators, who soon dispersed off from the spot.

As Agha was recalling golden days of his life, Shaheen came in with tea. With great efforts Agha positioned himself and took a sip. Before Shaheen could leave, Agha passed some remarks to his wife, which again lit the room with laughter.

While posted as DC Jammu, Agha once issued an arrest warrant against some Praja Prarishad leader over organizing frequent protests against Bakshi government. “Bakshi was afraid of hindus from Jammu and would always keep them in a good humour,” he claims.

During typing an arrest warrant, his head clerk misplaced the carbon page beneath the writing pad. This created comedy of errors. The arrest order thus read: “I, Agha Nasir Ali, district commissioner Jammu orders an arrest warrant of Agha Nasir!”

When the copy of the order went to High Court, the incarcerated Praja Parishad leader was released as judiciary found nothing written against him in order. During the same time, Agha was transferred to Kashmir as DC. “After his release, the Praja Parishad leader visited my Srinagar office and told me that he was set free,” Agha recalls.

Being a tough administrator of his time, Agha was close to both Shiekh as well as Bakshi. “They were both hard-hitting, so they wanted a bold officer in their regime to run their show,” Agha recalls.

He once arrested a President of National Conference in Jammu. The next day, NC workers of Jammu informed Shiekh about the incident. “Shiekh reprimanded his party workers for complaining against me and told them that he had given them best officer from Srinagar to head administration in Jammu,” he says.

But it was not only Agha’s stern administrative acumen which made him irresistible for the leaders of his time, his dressing sense and fashion consciousness equally contributed to his overall personality. “I and my late younger brother, Agha Shaukat Ali were considered best dressed men of our times,” he asserts.

But Agha’s married life was far from smooth and trouble free. His first wife succumbed to blood cancer three decades ago. His mother begum Zafar Ali, the first female matriculate of the state forced him to remarry. He then tied nuptial knot second time with Shaheen Agha, who originally hails from Allahabad.

As he advances in his life, his memory is failing him. But with reminiscence of past, he shared one interesting event of his life. Agha was newly inducted as DC Kashmir when his pandit head-clerk had brought an appointment order of a Muslim for his signature. But Agha dropped the name of Muslim and instead appointed a pandit. The same was repeated number of occasions.

This spread a word among pundits that Agha has a soft corner for pandits and was known as pandit nawaz, (hindu patron) among them. But, he soon changed his decision. “After that whenever the name of pandit was being forwarded to me, I would instead appoint a Muslim. As an administrator, I knew which decision was to be taken and when,” he recalls.

Now, as he is approaching to his life century, Agha, once bold officer of the state is only getting weak and frail. He no more wears white uniform to play tennis he was once very passionate about. He spends his days either reading or watching television now.

As I finally bid him adieu, stern looks flashed back on his face. With an apparent grim in his eyes, he looked outside the window. Clouds had already covered the sky. He kept staring at it, perhaps to have a glimpse of sun, which already had gone into hiding.

Good piece. Could have been great had Agha Sr told the reporter about the conditions that existed in Kashmir in 1930s and what happened during 1947. He was in service and might have seen things very closely. That aspect would have given this piece a historic status. Can it still be done??

I know the respected family. I studied in srinagar and lived with Begum Zafar Ali for a couple of years. She was such wonderful lady and I learnt a fortune from her.