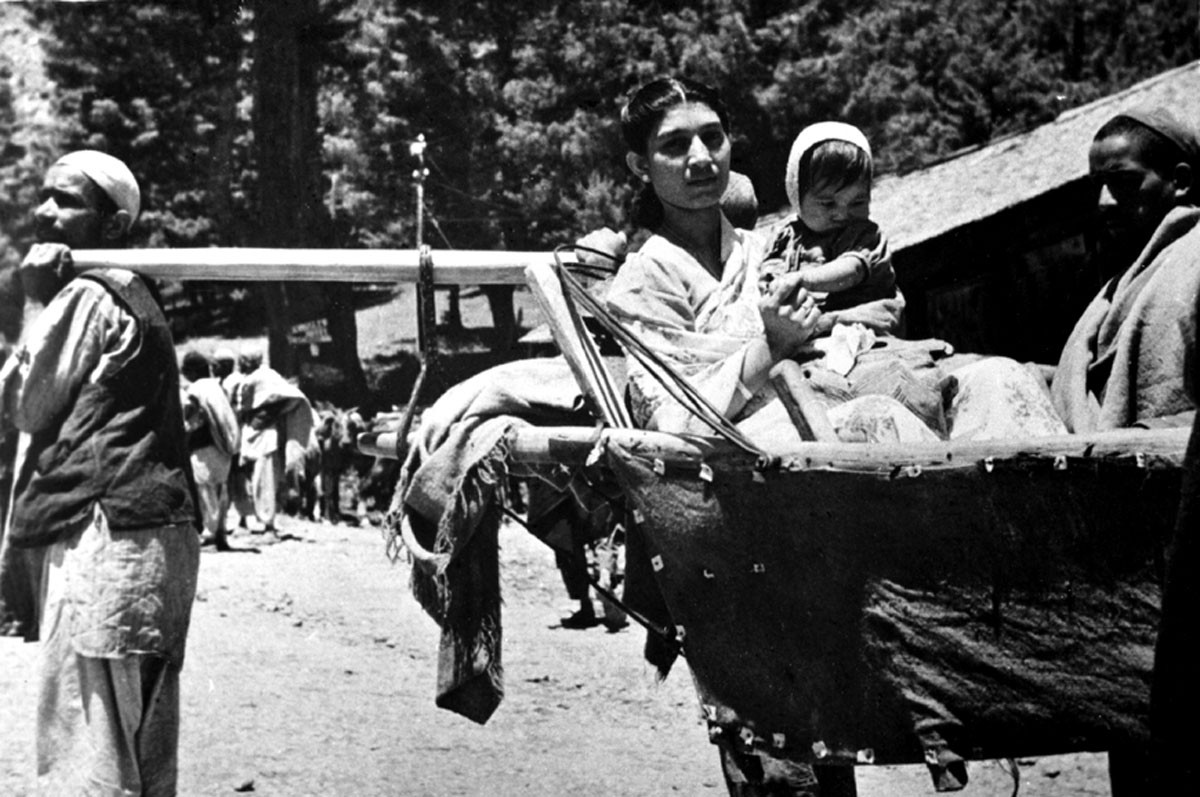

The forced labour was part of Kashmir’s centuries’ old economic exploitation that killed generations in the service of the despots. Muzamil Rashid explains the evolution of the system that ended slightly before 1947

“The most oppressive institution which broke the back of the peasantry in Jammu and Kashmir was the institution of Begar. The genesis of Corvee or

Begar (forced labour) in Kashmir may be traced to very ancient times.

Probably the first reliable reference to it is found in the Rajatarangni when king Samkaravarman (883-902 AD) employed villagers to carry the baggage of and supplies for his armies. There is a mention of Begar also in the time of Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin (1420-1470 AD) and also during the reigns of his successors. During the Mughal rule, this developed into a regular institution, particularly when huge armies of porters were inquired to carry the baggage of the emperors and their retinue during their frequent visits to the Valley. The Mughals were followed by the Afghans and the Sikhs and these harsh masters were most dishonest in the employment of the forced labour.

It was because of the institution of Begar that the people not only sold their shadowy rights in the land but also migrated to the plains so as to save themselves from this oppressive work.

The transfer of Kashmir to Maharaja Gulab Singh (1846-1857) in 1846

The AD, led to the momentous consequences, affecting the life and conditions of the people of Kashmir. In addition to over taxation, what fell like a dreadful pestilence on the cultivators in the midst of their working season was the iniquitous institution of Begar (forced labour). It is interesting to note that the whole demand of Begar was thrown on the Khalisa peasants as along with the city and town population; however, Pandits, Peerzadas, Sikhs and the peasants of the privileged right holders were exempted from Begar.

Begar was of two kinds: underpaid labour and forced and unpaid labour. The most pronounced one was that labour which was demanded from the peasants for carrying loads. The physical geography of Kashmir and the absence of modern means of communication demanded a sizable labour class for transportation purposes, but during the Dogra period, this demand assumed enormous proportions owing to two factors.

First, because of the threat of the Russian expansion, a big military garrison was stationed at Gilgit which necessitated the carrying of goods to and from Gilgit. Therefore, there emerged a fresh urgency of making a sufficient number of labours available who would ensure the transportation of supplies and luggage to and from Gilgit.

Secondly, we find that during the period under study, there was a great influx of European visitors and officials into Kashmir. In the absence of any modern means of communication, it generated a further increase in the demand for load carriers. Since for economic and political reasons, the State could not avoid the responsibility of providing all the facilities to the visitors and officials, the rising of labour-power of load carriers became an important feature of the Dogra administration.

The Begar to Gilgit was not only unpaid labour but also brought risk to the life of a peasant as there were least chances for his return because of the thirst, hunger and harsh weather conditions. Besides, the long absence of the peasant left his land unattended and therefore caused a great loss to him and thus starvation due to the shortage of food. The institution of Begar was made much complex by the inefficiency of administration which left corrupt officials free to exploit the situation and thus extracting money illegally from them to fill their purses. The harshness and the inhuman attitude of the Begar institution were such that even those who were attending their patients, carrying their personal urgent works or were newly wedded couples were not spared.

Not only this, the peasantry was pressed for road construction, a carriage for both officials and private and also to cut down wood from the jungle for the royal use. The institution of Begar encouraged the institution of Khana-Damad (a type of marriage where the male was to live with the family of in-laws).

The maladministration of the Dogra State necessitated the intervention of the Colonial State (British). To improve the administration, a council of five members was constituted which took the first step to mitigate the sufferings of people in 1891 when the task to deal with Begar was entrusted to R L Lagon.

After carefully analyzing the Begar system, he submitted a report to the Maharaja. His proposals suggested the fair distribution of Begar among all the inhabitants of Kashmir and also advocated for its continuance with some modifications. He recommended that all cultivators whether cultivating the State land or of Darmarth Trust, be held liable to Begar and that the inhabitants of Srinagar also take a fair share of Begar.

In 1891, a department known as Civil Transport Department to regulate the Begar system was established with the chief objective to abolish Begar and imposes an additional cess (tax) on land revenue to organize a paid establishment for working the transport system. The transport department was provided with 1000 coolies from Kashmir valley on the remuneration of Rs 5 to 6 per month.

In 1894, the Maharaja granted full propriety rights over wastelands in favour of Dogra Rajputs on moderate terms including absolute exemption from Begar. In 1898, new rules were framed to improve the Begar system under which the revenue member in concurrence with the Resident’s approval exempted the Markabans employed on the Gilgit transport service for one month against a single trip and for 1 ½ month for a double trip to Gilgit and back and the certificate (Parwans) permission of exemption were issued by the head of the administration (Hakim-e-Ala).

In 1900, Begar was abolished in principle but used in the event of an emergency. In 1910, the governor of Jammu brought the evils of the Begar to the notice of the State Council in which he informed that those taken away for forced labour were either not paid at all or partly paid. Besides they had to wait for a long period to receive these meagre wages resulting in that money hardly reached their pockets at all. In 1913, the Revenue Member suggested strongly entrusting the work of payment to the concerned Tehsildars and Lamberdars, but the corrupt officials hardly made the system to improve.

In 1916, the governor in consultation with Settlement Commissioner recommended for exemption from Begar, certain classes of people such as Pundits, Peerzadas, Syeds, Sikhs, domestic servants of high officials, privileged classes, Jagirdars, Lambardars, Ziladars, Patwaris, village menials and Chowkidars, persons attached to religious institutions like Imams, Pujaris, Bhais and Shrine Khadims, aged or infirm males, females, minors and others physically unfit persons rendering special services to Maharajas, cultivators (Kashtkars and Chowkidars).

In 1920, the State took an important step to abolish Begar and decided to grant an exemption to a greater number of people. Persons in the State Government Service, retired servants on pension, holders of war medals, members of the families of Lambardars, Chowkidars, Takavidars, Scout corps, non-commissioned officers of the army, shopkeepers, blacksmiths, religious leaders, Waisutis (men to look after the Khuls), carpenters, dooms, kamnis, Rajas, members of respectable families, servants of European and Indian gazetted officers, aged men, women, children and disabled persons, all were exempted from Begar.

Now the impressments of labour were restricted only to the Zamindars during an emergency. On the issue of the All India Kashmir Muslim Conference regarding the continuance of the institution of Begar, the Revenue Member tried to explain the nature and meaning of Begar prevalent in Kashmir by stating that, the term Begar under the existing rules means only the liability of supply of labour on full wages to meet the requirements of the administration.

In 1925-26, the word Kar-i-Begar was replaced by the word Kar-i-Sarkar and the forced labour extorted by the visitors and private persons was prohibited. In spite of all, these measures the revenue officers extorted Begar from the villagers without paying them a single penny although the rules prohibited this.

After 1947, the political transformation with the changing nature of State ushered a new era in the history of Kashmir. It was only after this that the real changes occurred in the political, administrative and economic structure of State.

(This essay was excerpted from the pre-doctoral thesis (2012) of Muzamil Rashid. He worked on The Institution of Begar In Kashmir (1846-1947) as part of his M Phil in the University of Kashmir.)

A COMPREHENSIVE WRITEUP. WOULD LIKE TO CONNECT WITH THE AUTHOR FOR SOME MORE INFORMATION ON THE SUBJECT OF BEGAR.

REGARDS