What has become of the erstwhile Zaildar families who dominated the society till the 1950s? Have they reconciled with the loss of paisa, power and prestige? Hamidullah Dar finds out.

Sarva Begum, a frail, 70-year-old from Lalpora village in Islamabad, leisurely stretches herself on the balcony of her spacious house in the spring sun. Her newly born grandson sleeps nearby. Sarva keeps an eye on the child while his mother tends the kitchen garden. “A son was born in our house after many daughters. We take turns to attend to him,” Sarva said.

Sixty years ago, the birth of a son was greeted with great celebrations in her house. Sixty years ago, Sarva’s family were the Zaildars of the area. They owned more than 5000 kanals of land spread over several villages.

“When I was a girl we Zaildars celebrated the birth of a son by arranging feast for the whole of the Zail. Hundreds of tillers who worked on our lands would arrive at our Haveli (mansion) for weeks,” Sarva says with a sigh, “But now we celebrate it like others in the village.”

Nostalgia for the feudal days pervades the house. Shabir Bhat, her son and village head, gleefully boasts of his forefathers. He looks far and wide at the neighbouring villages, taking in the expanse. “We owned most of it.” His outstretched arm forms an arc, a marker of lost entitlement. Shabir grew up with the stories of more than a dozen servants attending the chores at the house and every small and major event in the area in the 1920s and 30s being performed only after the feudal lord, his grandfather, Ghulam Qadir Bhat would grant his approval.

Shabir now owns the massive, three-storey Haveli built with Deodar wood. The traces of feudal opulence linger in the decor and woodwork of the enormous rooms of the house. Shabir is now unable to maintain with his meager resources. The Bhats who once produced hundreds of tons of rice, buy their rice from a ration depot. Shabir now owns mere 15 kanals of land. “The drought had affected the crops and I couldn’t even produce enough for the family,” he said.

The change of fortunes might bring some relish to the peasants the feudals once lorded over. Abdul Ghaffar (name changed), an 80-year-old from Varnow village, who toiled on the lands that Shabir Bhat’s grandfather owned speak tells a telling anecdote. The Zaildar wasn’t cruel towards the peasants, Ghaffar says, but adding wistfully, “The Zaildar used to fill milk in place of water in his hookah to show his status to poor tenants like me.”

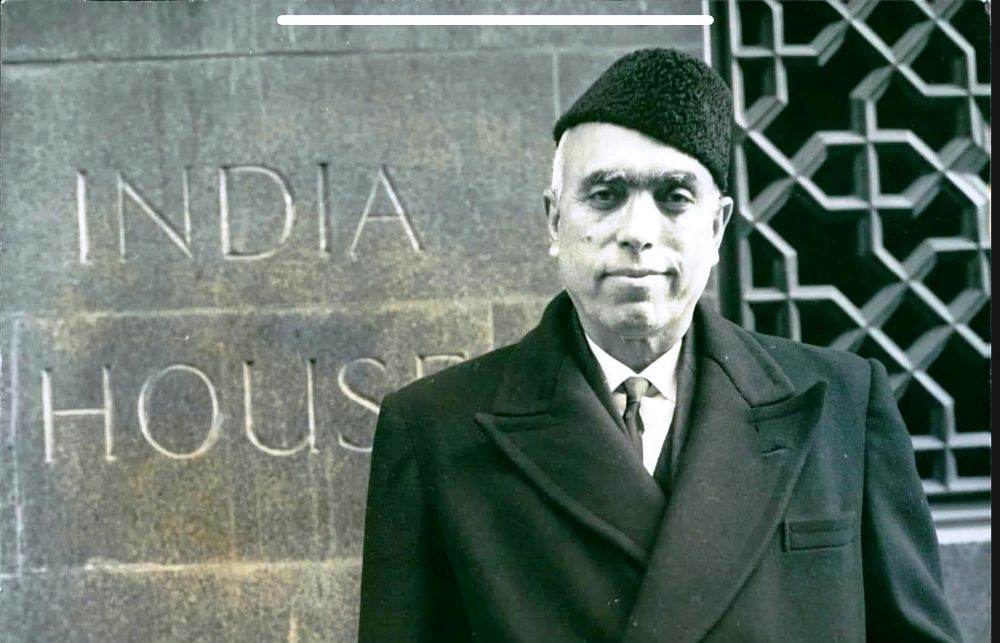

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s revolutionary Big Landed Estates Abolition Act 1950 popularly known as the Land To Tiller Act changed Kashmir’s social landscape, liberating hundreds and thousands of poor peasants and abbreviating the luxurious life styles of the feudal families of Kashmir. Once virtually ruling the countryside, the Zaildars lost most of their privileges overnight. As a result of the Act, no family could retain more than 22.75 acres of land. In all, 4.5 lakh acres of land were expropriated from around 9000 land owners, mostly Zaildars and 2.31 lakh acres were transferred to cultivating peasants.

“After buying Kashmir, the Dogra rulers thought that all the property of J&K including its human beings belonged to them. They had no knowledge of the countryside here and created the Zaildari system to work as a bridge between the rulers and the masses. Influential people got Zails to entertain officials who happened to visit their area in that age of widespread destitution,” says Prof. Farooq Fayaz of Kashmir University’s History department.

Bashir Ahmad Wani of Qasba Khul in Kulgam district is a Patwari in the revenue department. Wani’s grandfather Ghulam Mohammad Bhat was the last Zaildar of a Zail comprising of many villages. However, in 1950 their fortunes shrank. “Ours was the only Zaildar family here. We had over 2000 kanals of cultivable land that was cultivated by tillers on a share basis. My grand father had scores of granaries to dump more than 200 tons of paddy accruing from the lands,” Wani said.

Wani’s grand father had a mansion that had every conceivable facility in it. “He was a king in himself. In the morning hundreds of the people used to visit his mansion to solve their disputes, seek permission for certain works and take orders in matters of running the Zail,” added Wani. Afterwards Zaildar would take a hot bath and settle for a lunch of Mushk-i-Budij, a sweet, fragrant rice, and chicken fried in ghee and precious spices. Then a siesta followed after which Zaildar would visit his lands. “One person used to hold reigns of a well-bred horse and three persons would follow him, implementing every command given by the Zaildar.

Tillers from the villages through which my grandfather would pass would mop the roads as a mark of respect for his generosity,” Wani said, with a tinge of pride. The house of the Wanis is a ruin today; the new order, however flawed, had torn down the old.

Kashmir had three thousand such families. In Mattan, the Zaildar Khawaja Asadullah Ganai had 1300 kanals of cultivable land. Salahudin Ganai is a descendant of the Zaildar of Mattan. After the transition to the new order, they lost 1500 kanals of land. The question was how to adjust to the new world and the answer was education. “My father Khawaja Mohammad Akram Ganai, the last Zaildar, invested his resources in the education of the family and that produced some top bureaucrats including present principal secretary to chief minister Khurshid Ahmad Ganai,” says Salahudin.

There were some unique features in the life style of Zaildars. “Zaildars used to build their mansions outside the villages on a scenic piece of land. They would keep distance from the peasants except for their duties regarding the administration of the Zail where they had to dispense justice and maintain law and order. Their women practiced Purdah and seldom mingled with other women of the village. It was elitist class with its own customs. The houses were surrounded by walls and had beautifully decorated Baladaris (meeting halls). There was no harem in these mansions,” says Prof Farooq.

Also, they rarely married outside the Zaildar families. “First preference in the matter of marriage was given to Zaildar because of the similarity in customs, life style and social status. However, the trend is now changing and character has taken precedence over social status,” says Salahudin. The house of the Zaildar-i-Mattan looks a ghost house today. A three- storey huge building with a vast courtyard dotted with decorous pine and willow trees and a stream running nearby circumventing the house, has no inmates as the officer-rich clan made luxurious houses at a distance from it.

Salahudin’s guest room has a photograph of Saleh Ganai, the first Zaildar of the family hung on a wall. “I put it there to show everyone that our ancestors belonged to elite class,” Salahudin says smilingly.

The houses of the Zaildars are in ruins barring a few where the families still put in like Bhat’s of Lalpora. Prof. Farooq seems dismayed over the abandonment of these houses. “They are the treasure of our architectural heritage. In the countryside the presence of such structures keeps the people reminded of a past that had an institution called Zaildari system. I have been to many places a few decades ago and witnessed the progeny of the Zaildars helping peasants resolve their problems and issues pertaining to land and family,” he said.

At Drugmulla in Kupwara district, the sprawling mansion of late Zaildar Sanaullah Shah stands like an architectural jewel in the area. No other house in the entire belt is any comparison to this 125 x 40 feet building having huge halls and verandahs. Halls have wood work ceilings and were painted one hundred years ago. “They retain the same brightness and texture even today,” said Ghulam Hassan Shah, grand nephew of Sanaullah.

Sanaullah had houses each at Kupwara, Baramulla, Handwara, Sopore and Srinagar, besides a houseboat in Jhelum near museum at Lal Mandi Srinagar. “He was living a king’s life. He had a servant just to put embers in the Hukka,” Shah said.

Sanaullah was member of the Dogra Assembly in 1932 representing entire North Kashmir. And in those days when Sanaullah used to visit his Zail, “People would follow him in a congregation. His motor car used to be touched by the people who had never seen it till then,” says Hassan.

In the entire Pahalgam-Salar belt there are interesting anecdotes about the Zaildar-i-Salar Ghulam Mohi-ud-Din Mir who was a contemporary of Hari Singh. A pious Muslim, Mir was the ultimate manager of conducting the Amarnath Yatra. “It was his duty to arrange, from labourers to ponies,” says his grandson, legislator Rafi Ahmad Mir. Of the vast estates that he owned, the prized was an orchard of walnuts and almonds. It was set up over a huge piece of land in Banad-Sheikhpora and all the trees were of kagazi variety. “There was no road to the village and my grandpa employed people to carry the water on their heads for 2.5 kilometres when the saplings were planted,” said Rafi. “There are 200 trees and the entire produce has been supplied to markets in Bombay for around a century now.”

Mir’s son Ghulam Ahmad was taking control of the estates at a time when Kashmir’s struggle to throw away the monarchy was at its peak. “My father was a revolutionary and he joined Sheikh Sahib regardless of the massive costs it entailed for him,” said Rafi. His father, who became a close associate of Sheikh Abdullah and later a member of the constituent assembly, lost over 3000 kanals of land in the land reforms.

In 1947, the family ferried 40 Hindu families from Srinagar and made them comfortable in their mansion because they were apprehending trouble in wake of the large scale massacre of Muslims in Jammu. Mir died in 1991 after being in active politics for around forty years. Their switch to politics helped the Mirs of Salar remain relevant in the new order.

After militancy broke out, Rafi Ahmad Mir, like all other NC workers fled from Kashmir but the locals went in a delegation to him and got him back. He was perhaps the lone NC man who never migrated from Kashmir. Mir, once fought against Muftis’ but after the NC “told him” that it was difficult to go against the father-daughter in the belt, Rafi joined PDP.

The aesthetic sense of Zaildar-e-Bow (Rajpora in Pulwama) Aziz Mir, can be gauged from the mansion he built a hundred years ago. Situated on a higher patch of orchard land, the 16-room mansion had besides other things several bathrooms and a huge dancing hall. And a hydro powerhouse was built and operationalised near the mansion to light up the mansion in 1939.

“It illuminated the mansion and three houses in an era when only Maharaja Hari Singh had electricity in his palace. It remained functional till 1947”, said Ghulam Hussain Drabu, grandson of Aziz Mir.

Sir Walter Lawrence in his magnum opus, The vale of Kashmir, refers to Qudus Mir, father of Aziz Mir, as the most progressive landlord of his times. He laid orchards of many varieties on scientific lines. “We have orchards that have 100-year pear trees. Even seedless grapes and Quincey apples (Bamtsoont) were found in Mir’s orchards,” says Manzoor Hassan Drabu, who now resides in the huge mansion. “He laid stress on employment generation and in his times he had 200 employees doing different jobs. He invested in contract farming and most of the saffron from the area was sold through him. He had shops in Rawalpindi, Amritsar and even in Karachi where the exported Kashmiri fruits used to be sold,” adds Manzoor.

Aziz Mir was quite interested in education and established first school in Rajpora in early 20th century. “It was his (Mir’s) love for education that percolated to his progeny and today most of our relatives hold key position in Europe, America and Canada. He even helped Lawrence in the settlement of land records.”

Mir used to visit his wife at Maharaja Bazar where he had built a mansion for her in Shah Jahan style. And after Mir’s death the family purchased back the mansion when his widow remarried. “He had also built a stable for his horses at Rambagh that now houses SIDCO headquarters. He was so rich that even Maharaja at times would take loan from him,” says Hussain.

Mir married off his daughter to Ghulam Hassan Drabu of Narwara Srinagar who later took over as Zaildar-e-Rajpora. “He was ahead of his times and expanded his business far and wide besides investing in education of his children. He had friends in entire North India and he used to arrange get-together with them in the hall,” says Hussain. They lost 1446 kanals of land to the Land to Tiller Act (1950), but education and their contacts with the wider world helped them make the transition to modernity and a place in the new elite. One of his sons Ghulam Mohammad Drabu was political secretary to Prime Minister Ram Chander Kak. Many more followed in major administrative positions.

The King is Dead; Long Live the King!

feudals and politicians only a thin and most of times diffused line separates the the two subclasses of the same class

This comment we had received on February 6, 2010 on a different e-mail:

I came across the cover story “The fall of the Feudal”, published in the 15th May issue. It reminds me when I was a child and uses to hear the stories of Zaildars and Jagirdar families from my father. When I read the cover story I recollect all about the families I have heard about.

This has become legend now a days that the Zaildars were living the life of Nawabs though some of the Zaildar families still maintain the same dignity as they used to, but some families have altogether faded and vanish with the span of time and period.

Take the example of Aziz Mir Zaildar, Rajpora his all grandsons are highly educated and were posted on the key posts of Administration in the State of J&K. his grandson Ghulam Hussain Drabu is looking after the ancient property he (Aziz Mir) left behind including the huge orchard with all modern techniques available for abundance and quality production. Ghulam Nabi Drabu another grandson of Aziz Mir, well known personality in the state Administration retired as Commissioner Exercise and member PSC a very pious and humorous person.

Besides Education Aziz Mir had a great interest and good taste for living, his mansion even today has a grandeur look through built hundred years back. At end it is the fortune wheel that turns round and round.

Asif Mirza

24-Swamy lane,

Ishber Nishat, Srinagar.

Cultivation of farm land like any other economic activity depend on the scales and Economies of scale determines the profitability or otherwise of farming activity as well. The larger the area ,wider the cost spread and thus lesser the per unit cost of cultivation and higher the returns. Over the period of time in the post land reform period the no of marginal farmers in the state have increased and today most of the farmers fall within this category. This raises a question mark on the very economic viability of the farming and the consequent results like farmers looking for other sources of employment and the pressure on the govt as the major employment provider. This is a country wise phenomenon and the union agriculture ministry toyed with many ideas to combat this situation and sustain growth in the agriculture sector. One such idea was to introduce contract farming. In our context we find that a very good no of the tillers to whom land was gifted gratice sold it out, converted it to non agri use or all together stopped working on these farm lands employing labor from Bihar to work for them and hanker for casual labour jobs in the govt. thus while we may take pleasure in reducing the old zailder family to patwaris and the like we have also to rue the consequences of these reforms that are getting worst with every passing day.

My compliments for quality reporting in Kashmir life. I am sure in the years to come it will be some thing all of us will be proud. Mark my words.