An administrator under Dogra regime, Salaam Peer’s actions at the time of ‘the great famine’ in Kashmir is still counted as one of his noblest achievements. His gradual fall from being an ‘influential’ person to a ‘nonentity’ calls some attention, Bilal Handoo reports.

Among the scores of withered remains of past in Kashmir, one of the most prominent possessions is the property of Salaam Peer in Srinagar’s old city. Peer, a former administrator in Dogra regime, passed away nearly fifty years ago but the story of his gradual fall continues to fascinate many historians and ordinary people living in Kashmir.

At the time of Dogra monarch Pratap Singh’s rule when most parts of Kashmir faced a famine due to floods, there was an acute shortage of food grains. The situation was so severe that some people kept food grains hidden from their relatives and neighbours.

“It was the same period when Salam-ud-din Shah aka Salaam Peer headed one of the provinces of Dogra regime in Kashmir,” Zareef Ahmad Zareef, a noted social activist and a historian, says. “Peer ordered to erect gallows, though fake ones, and issued a decree that whosoever would be found in possession of food grains would be executed in public.”

This ‘stern’ proclamation soon began to show results. Scores of people surrendered the holdup grains and assembled it in a public granary. “Not only this able step taken by Peer thwarted mass casualties due to starvation but it also put a check on malpractices in the autocratic society of that time,” Zareef says.

There was a Pandit baker in the same period, says Zareef who, under the pretext of famine, made underweight bakery products. “Once Peer got to know about it, he ordered his men to tie footwear (puhoul) to his ponytail. The decision checked the menace and deeply embarrassed the pandit and many of his ilk who resorted to such malpractices. This stern action was the call of times and Peer, as an administrator, took it with full wisdom for the larger interest of the society,” Zareef says.

Many people living in close proximity to Peer’s residence situated in old city’s Khanyar locality fondly remember his gesture during the famine as Salaam Peeroun Souch (Salaam Peer’s goodwill). Abdul Sattar, 85, who has seen Peer during his youthful days, recalls him as a man of conviction and an able decision-maker. “When he used to come out of his house riding a horse, locals wouldn’t dare to face him. Such was the influence of the man,” he says.

Salaam Peer was one of the scions of Naqashbandis in Kashmir. Many say his family background played an important role in his ‘tall’ stature among people, apart from being an able administrator. “His family members would never come out of their home in case of rain, fearing dirt might spoil their clothes, and thereby affect the sanctity of their prayers,” Sattar says. It is believed that Peer knew English at a time in Kashmir when people believed that learning English would make one Kerre, implying a Christian.

During Dogra rule in Kashmir, the whole valley had been divided into three provinces – Islamabad, Baramulla and Muzaffarabad. Peer was heading Islamabad region that comprised of Srinagar as well. He remained in administration in the later years of Pratap Singh’s rule and in the early phase of Hari Singh’s regime.

“Throughout his tenure as an administrator, he sagaciously ran the state of affairs,” ZG Mohammad, an author and a noted columnist, says, adding, “The impact of his administrative skills was so palpable on Kashmiris that a Kashmiri phrase – Dabdab e Salaam Peer (Impact of Salaam Peer) – was coined after him.”

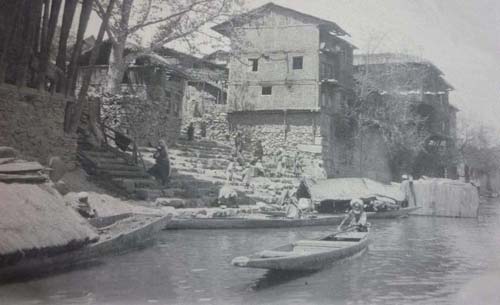

Under Dogra regime, boatmen carrying commodities used to set up shops on the banks in Jehlum in old city. Some people indulged in malpractices and would add adulterants to food grains. Besides, some boatmen carrying rice or wheat would also moisten broom in the river and then struck the gunny bags filled with grains with the broom to add the weight of water to them.

After Peer came to know about it, Zareef says, he himself checked the grains by inserting his own hand in the bag. In case, he found some mischief, he would order his men to strip the boatman and immerse him in water till he would pledge not to do it again.

“Such stiffness on Peer’s part wasn’t an indication of ego and highhandedness. Rather it was a testimony of his wisdom to have zero tolerance for misdeeds. This stiffness greatly checked corrupt practices in society,” says ZG Mohammad.

Progeny Woes

Peer appeared to be in command in his life till his progeny became a cause of concern for him. He was a father of two daughters and a son. His first shock as a father came soon after 1947 when his only son, Hisaam-ud-Din, was sent to Pakistan in exile. “Hisaam was sent to Pakistan by Shiekh Abdullah as he was against the conversion of Muslim Conference into National Conference that took place in 1938,” Zareef says.

While Peer was longing for his son, it started affecting his health. At the same time, one of his daughter’s affair with Gurpurab Singh, the manager of Srinagar’s erstwhile Palladium cinema surfaced. Zareef says his daughter was the most glamorous ladies of that time. “Riding a horse, Peer’s daughter would move around the places. In fact, she had developed infatuation for cinema and later got married to a Sikh,” Mohammad Ismail, a neighbour of Peer family in Khanyar, says.

But the marriage was soon dissolved. Historians have written that the Sikh husband of Peer’s daughter divorced her owing to the pressure created by his relatives. The divorced daughter of Peer was soon seen begging on the roads of Srinagar. “I have myself seen how her plight became worst than a beggar some forty years ago,” Abdul Karim, 81, a local resident in Khanyar, says.

Karim says her plight caught the attention of the workers of Jamaat-e-Islami who come to her rescue. “Basically Jamaat realized how her father had done some meaningful contribution to help Kashmiri people in times of famine, and how his able administration checked the malpractices in society,” Karim says. Peer’s other daughter was married to one of reputed families of Srinagar.

Legacy Lost

At his Khanyar residence, many people say that Peer’s garden was much more spectacular than Mughal gardens when he was alive. Besides, his property was itself an architectural marvel. “You name any fruit or flower of the world, it was grown in Peer’s garden,” Manzoor Ahangar, a local travel agent who used to secretly pluck fruits from Peer’s garden in his youth, says. There is a burnt coconut tree that still stands in the lawns of new owner of Peer’s residence that caught fire mysteriously during early nineties. Besides, many Chinar trees have been axed over the period of time.

“I swear upon Allah, had the garden been preserved, it would have been a vintage tourist spot in Kashmir at present,” Ahangar says.

Peer’s property swelled up to the banks of Brari Nambal Lagoon in Baba Demb area of old city. As per some elders in Khanyar who have seen Peer’s property, a major portion of the land of his garden was annexed to Nalla Mar road in mid sixties under the regime of Ghulam Muhammad Sadiq. “While Nalla Mar devoured some part of his garden, the other part of garden houses present day Khanyar Police Station as well as Gousia Hospital,” Mohammad Sultan, an elder in a locality, says.

Peer’s house and a portion of his garden were sold out to a family in Baramulla who used to sell merchandise in Zaina Kadal with the help of Shiekh Abdullah, locals claim. In 1973, it was brought by Shiekhs at Rs 3 lakh.

With Sheikh Family purchasing Peer’s legacy, elders say the present generation has been deprived of a real treasure!

“JAMAAT I ISLAMI’s GLORIOUS ERA”