After being legally protected for 108 years, Kashmiris find themselves out in the open as reservation rules replace Residency rights. Haseeb A Drabu analyses the legal, constitutional and jurisdictional status in historical context. Is Kashmir back to 1912 when non-locals would become state subjects on an 8-anna stamp paper?

The state of Jammu and Kashmir had a domicile law. It was enshrined in the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir and endorsed by the Constitution of India. It was not an ordinary legal right; it was a statutory right.

The Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir doesn’t have a domicile law. What has been notified by the UT administration is a set of rules for employment in the government. It is only a “requirement as to residence” for a government job. Far from a constitutional right, the way it has been conceived, formulated and notified, it may not even be enforceable in a Court of Law.

Critical and Contentious Change

On March 31, 2020, as a part of the exercise to adapt and align the state laws of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir with its new stature as a Union Territory, Government of India amended 109 and repealed 29 state laws. Amidst this bulk re-adaptation of laws, a critical and contentious change was introduced in The Jammu & Kashmir Civil Services Decentralisation and Recruitment Act, 2010 – the words “Permanent Residents of Jammu and Kashmir” with replaced by “Domicile of UT of Jammu and Kashmir”. This was not a mere substitution of words.

First, the Act deleted a constitutionally validated term defined in section 6 of the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir and guaranteed by Article 35A of the Constitution of India. Second, it was replaced by a term that has no Constitutional basis or even legal basis in India. Third, Section 3A of the Act defined the expression “domicile” explicitly only “for purposes of appointment to any service in Union territory of Jammu and Kashmir”.

No New Domicile Law

The implications of this definition go way beyond the ambit of government jobs and its inferences have a bearing beyond the strict remit of the definition. This is so because historically, domicile in Jammu and Kashmir has been associated with rights and privileges for state subjects.

Not surprisingly, this change is being seen as an “amended domicile law”, which it is not. The two largest mainstream political parties – National Conference and People’s Democratic Party – rejected this “amended domicile law”. The fact is that now there is no “domicile law” now.

On May 18, 2020, the UT administration notified a set of rules, Jammu and Kashmir Grant of Domicile Certificate (Procedure) Rules 2020. It is important to understand that the word `domicile’ has been used in these Rules only for prescribing domiciliary requirement for reservation in government jobs and admission to educational institutions situated within Jammu and Kashmir. Not to grant domicile status, which existed under the Jammu and Kashmir state subject law.

The word ‘domicile’ used in the Rules is in the loose sense of permanent residence and not in the technical sense in which it is used in law.

Then and now: Antecedents

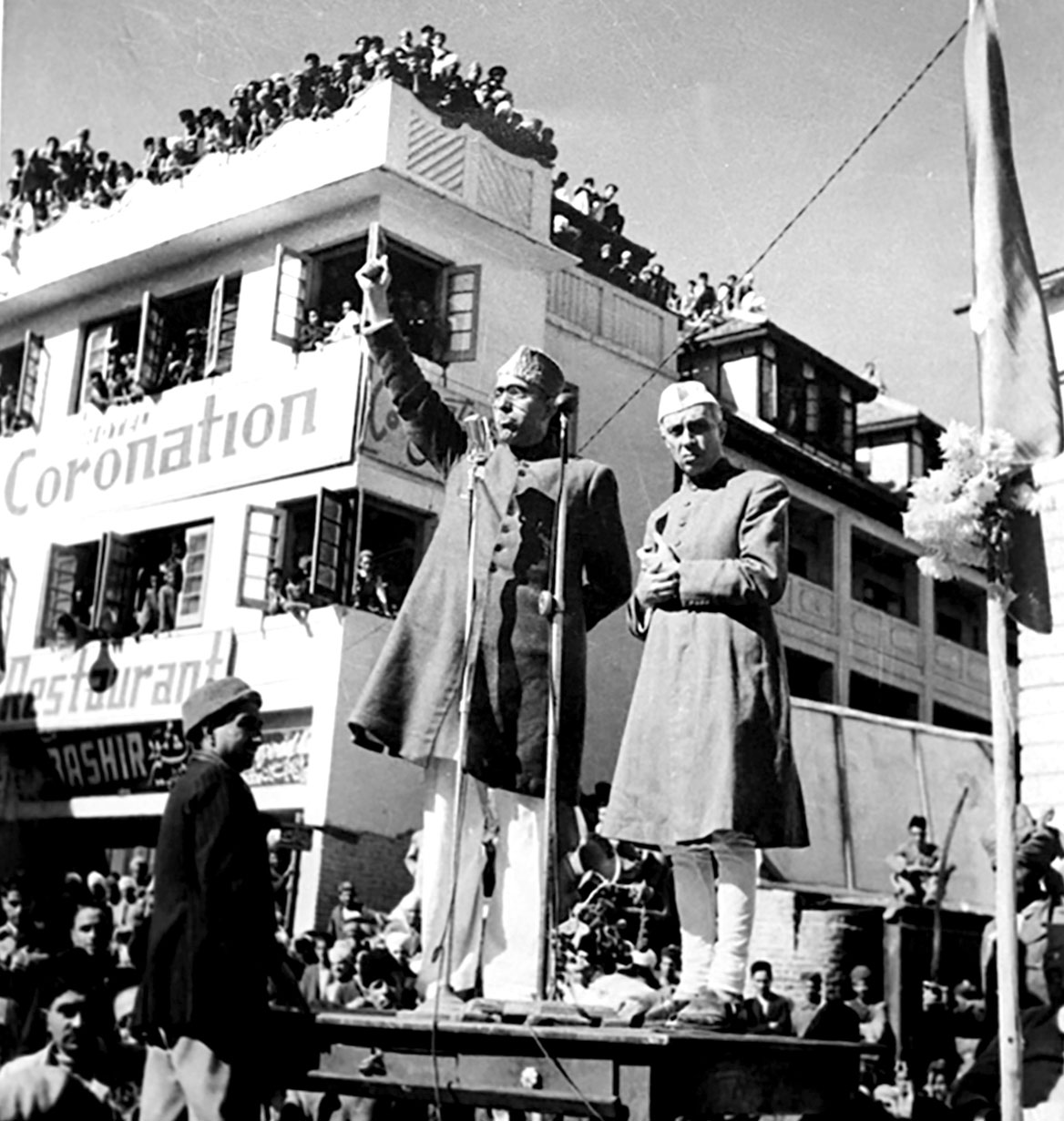

It is interesting to note that the rules for domicile reservations notified by the UT government are strikingly in line with the state subject notification of 1912.

Contrary to popular perception, the State Subject Notification of 1927 issued by Maharaja Hari Singh was not the original state subject law. It was a revision of the criteria in the State Subject law promulgated in 1912.

For the first time, 1912 domicile law placed state subjects who had lived in the State for generation on the same footing as outsiders who had acquired a rayatnama (special order) from the Maharaja.

The 1912 definition of “State Subject” was the following:

(1) All bonafides subjects of His Highness the Maharaja Sahib Bahadur.

(2) All persons who have tendered a duly executed rayatnama and have acquired immovable property in the State.

(3) All persons who have resided within the State territories for not less than 20 years and are subject to the laws and regulations promulgated from time to time by His Highness the Maharaja.

(4) The descendants of the persons mentioned in the foregoing clauses that though not State Subjects had not less than ten years worked of approved service in the state.

Notice that (3) and (4) of this law are exactly the same as clause ii and iii of the Rules notified now. Especially including the central government employees.

Though 1912 notification linked the legal definition of Kashmiri subjecthood with education and consequently, employment in government service, it was ineffective in curbing the influx of non-Kashmiris.

The unsatisfactory nature of the 1912 definition was that any person can obtain rayatnama on an eight anna stamp paper to own land and declare himself a State Subject.

Moreover, the fourth clause of the definition was meaningless since most of the non-mulkis had worked in the State for at least twenty years. As such, the law was revised making it stringent and extensive by adding exclusive property rights. It is this revised law that was promulgated in 1927!

More than a hundred years later, the conditions have made a comeback albeit in a different garb!

Legal Implication:

Not by Origin, but by choice

Not only does the changed usage of the term “domicile” dilute the rights associated with it in Jammu and Kashmir, the new definition goes beyond liberalising the norms for “outsiders” to take residence in Jammu and Kashmir. The fundamental change that has been made is undoing the principle of “domicile of origin” that the State subject law was based on. And allow a residency based on the principle of “domicile of choice”. Adding “subsidiary safeguards” in terms of the number of years in residency as qualifiers is neither unique nor protective.

The state subject (as the domicile of origin) acquired at the time of birth, was a “creature of law”. It conferred a right that would not be obliterated even after taking residence elsewhere in the country or abroad. It would continue to remain valid without any time-bound criteria. It was there in perpetuity. It contained within it the conception of domicile that relied on ethnic origin as a marker of belonging.

Most significantly, it did require being regained or reconstituted animoet facto in the manner which is necessary for the acquisition of a new domicile. The fact that now a state subject who has been residing there for generations has to regain his domicile status is adding insult to injury.

This has been replaced tangentially by the “domicile of choice”; fundamentally a self-acquired domicile. In fact, the domicile of choice is a conclusion or inference which the law derives from the fact of a person fixing “voluntarily” his residence in a particular place. It is at best a description of the circumstances which create a domicile, and not a definition of the term “domicile”. Let alone a legal one.

The real issue is that the new regime of domicile rights in Jammu and Kashmir strikes at the roots of the notion of who belongs to Kashmir. The rules obliterate, through redefining, the ethnic conceptions of belonging that was sought to be protected by the domicile law in the first place.

Constitution and Domicile

The Constitution of India recognises only one domicile, namely, domicile in India. Article 5 of the Constitution is explicitly clear on this point; it refers only to one domicile, namely, “domicile in the territory of India”. There is no mention or provision in the Constitution of India about “domicile of a state”. So a domicile of a state is not statutory.

State subject as domicile was Constitutional. Jammu and Kashmir was the only federal unit within the Union of states which had the legislative competence to define “domicile” in a legal and technical manner, which it had done. Also, in Jammu and Kashmir, many branches of law were within the competence of the state government and for purposes of those laws the state subject was “domiciled in Jammu and Kashmir only”. In a sense, domicile in Jammu and Kashmir was a subset of citizenship of India which is the case only in some federated countries. But despite having some features of a federation, India is a Union of states and domicile cannot be a subset of Citizenship. Now that not being the case there is no way in which the UT of Jammu and Kashmir can bring in a “Domicile law”. As such, the domicile certificate has no real meaning and is in not in any way comparable to the PRC.

State Subject Versus Domicile

Even etymologically, the term “state subject” is very different from domicile. In English Law and usage, the term “subject” is used as a synonym for national. It stresses the quality of the individual as being subject to the Sovereign. Originally, State subject was a “feudal concept of nationality prevailing in Anglo-Saxon law. It regarded nationality as a territorially determined relationship between subject and the Sovereign by which the subject is tied to the King in person, by the bond of allegiance”. Which is why in countries with a republican constitution the term “subject” is rarely used and is unpopular; it has been replaced by the term “citizen.”Domicile, on the other hand, in conception, is not determined by any territorial link. It is a purely personal/residence relationship. The word `domicile’ is meant to identify the personal law by which an individual is governed and his personal rights and obligations are determined. To compare the two, state subject represented a person’s political status; domicile indicates his civil status.

The state subject was not defined for pecuniary personal purpose. It was a right that had implications on education, employment, and property. As against this, domicile is for a particular purpose. It is not a right. What has replaced the state subject right is a 100 per cent reservation in government jobs and education. This as shall be argued below, will most be likely struck down by the courts.

Supreme Court on “State Domicile”

The Supreme Court has on more than one occasion made it very clear that there is no legal basis for the concept of domicile in any state of the Union.

Chief Justice, P N Bhagwati, heading a three-judge bench pronounced in Dr Pradeep Jain vs Union of India,198, that “The concept of `domicile’ has no relevance to the applicability of municipal laws whether made by the Union of India or by the States”.(Municipal law here includes national, state, provincial, territorial, regional, or local law as against international law).

Elaborating on the concept of “state domicile”, he noted, “It would not, therefore, in our opinion be right to say that a Citizen of India is domiciled in one state or another forming part of the Union of India. The domicile which he has is only one domicile, namely, domicile in the territory of India”.

Rubbishing the concept on what the notification issued by the Jammu and Kashmir administration is based, the Supreme Court has said, “When a person who is permanently resident in one State goes to another State with the intention to reside there permanently or indefinitely, his domicile does not undergo any change: he does not acquire a new domicile of choice. His domicile remains the same, namely, Indian domicile”.

In another judgement, it has been observed by the Supreme Court that “a person is domiciled in the whole of that country even though his home may be fixed at a particular spot within it”.

Indeed, the Supreme Court has warned against the use of the word `domicile’ in relation to a State within the union of India on the grounds that “it is highly detrimental to the concept of unity and integrity of India to think in terms of State domicile”.

For these reasons, the Supreme Court strongly urged upon the State Governments not to include to this expression ‘domicile’ in the rules regulating admissions to their educational institutions and particularly medical colleges. The Supreme Court has told the states “to desist from introducing and maintaining domiciliary requirement as a condition of eligibility for such admissions”.

Article 35 A & State Subject

Even after Jammu and Kashmir acceded to India, the people of the state did not automatically become Indian citizens. This happened with the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1954, which stipulated that the people of Jammu and Kashmir are citizens of India with retrospective effect from 1950. In fact, it was not until the Citizenship Act of 1955 that the state- subjects were formally made citizens of India.

In the rest of the country, erstwhile British India, the old British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act continued to apply in independent India till November 16, 1949. It might be recalled that the Constitutional provisions regarding citizenship was introduced, two months before the rest of the constitution.

This meant that those in the former territories of British India remained British subjects after the British had departed. The residents of Kashmir, however, had not been British subjects, they were at best British Protected Persons.

As such, state subjects of Jammu and Kashmir were not covered by the interim arrangements made for British India. So when the British suzerainty over the princely states terminated on August 15, 1947, residents of Kashmir ceased to be British Protected Persons.

For, the people of Jammu and Kashmir domicile under the State Subject law was the de facto citizenship from August 15, 1947 to May 14, 1954. Indeed, Hyderabad which was positioned similar to Kashmir even issued its own passports!

So, what Article 35 A had done was to reconcile and make the Jammu and Kashmir domicile an attribute of Indian nationality. It denoted the Kashmiri state subject’s place of residence as a citizen of India. In that sense, Article 35A was not a one-way street which benefitted only the people of Jammu and Kashmir. Back in 1954, it has critical value and played a major role in the integration of Jammu and Kashmir with the Union of India. But that, as they say, is history.

The point being made here is that the rules that were notified by the Jammu and Kashmir administration are on thin ice and can be struck down by the Supreme Court should anyone raise it. This is so despite the fact that so far the Supreme Court of India has only upheld the legal validity of domicile reservations. The reason being that the 100 per cent domiciliary reservation is unprecedented. Already there is a case in the Supreme Court on a similar matter.

All States Have Domicile Reservation

There is nothing unique about Jammu and Kashmir having domiciliary reservation. Many states in India have extended domicile reservation in educational institutions. The domicile reservation has been a part of the admissions to medical colleges for quite some time now. Apart from the medical colleges, more recently, state governments in Gujarat, Karnataka, Odisha and Rajasthan and the Union Territory of Delhi have extended domicile reservation in the National Law schools in their territory. There is domicile reservation in National Eligibility cum Entrance Test allowing state government to reserve up to 85 per cent of the seats for the students domiciled in the particular state.

The same is true of the 15 years qualifying criteria to avail of domiciliary reservations. Almost every state government/UT issues domicile certificates. This Certificate is required as proof of residence only to avail quotas for a resident in educational institutions and in the Government Service. To get the certificate, proof of continuous residence in the State/UT for a specified minimum period depending on the rules in the State/UT concerned is required. In many cases, the stipulated period is 20 years. The only provision that is unique is the granting of domicile reservation, as has been notified for those residing in Jammu and Kashmir on work of the organs of the state; central government and its subsidiaries.

Against International Norms

This rule is in complete contradiction of the basic principle of the domicile by choice; freedom of choice. It also goes against international norms and practices. It is an internationally accepted tenet, upheld in numerous court verdicts, that “residence for domicile rights” must be freely chosen and not prescribed or dictated by any external necessity such as the duties of office”.

Further, it cannot be fixed for any defined period or particular purpose but has to be general and indefinite in its future duration. In other words, for the domicile rights to be legally valid, the intention to settle down in a place must be free and voluntary. The inference is that as soon as the purpose of stay or generally animus manendi changes, the fact of domicile of choice gets extinguished by law.

As such, Section 3A, sub-section 1, clause (a) and Section 3A, sub-section 2, clause (a) of The Jammu and Kashmir Civil Services (Decentralisation and Recruitment) Act (Act No.XVI of 2010) fly in the face of the established tenets of the domicile of choice. Clearly, the “choice” is being incentivised and guided, if not ordered. The choice will be made by the government and only complied by the individual. Hence, it is contrary to practice.