Ladakh’s history and strong cultural and self-governance aspirations remained a thorn in the side of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Devolution into a Union territory has worsened the feeling of neglect and dominance among Ladakhis. In a border region with a fraught ecology, will the Indian government pay heed before this explosive mix bursts into flames, writes Shrikha Gowri

As the 2024 Lok Sabha elections reach a fever pitch, the focus may have shifted from the long-standing demands in Ladakh which culminated in massive protests earlier this year. But the demands and the campaign they have ignited throw light on many interesting aspects of federalism, cultural sub-nationalism and the politics of development.

So, why is Ladakh protesting and what is the unfinished agenda in the region?

A chequered history

Known for its scenic mountain passes, cultural diversity, strategic geopolitical position and, lately, immense economic potential, Ladakh was a part of the autonomous state of Jammu and Kashmir before 2019.

For much of its history, Ladakh has been an important transit zone on the Silk Road, which made possible trade between China and Europe. The eastern part of Ladakh currently administered by India, i.e., the Leh district, has historically been part of the Trans-Himalayan kingdoms of Tibet, while the western part— Kargil district— has had Central Asian influence.

Of course, this is a generalisation because parts of the Leh district, such as the Turtuk Valley, have a large ethnic Kashmiri Muslim population (who arrived as traders and settled there) while the Zanskar region in the Kargil district is mostly Buddhist and culturally more akin to Leh.

When the British made Gulab Singh, the Dogra ruler of Jammu, the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir after the Treaty of Amritsar in 1856, the kingdom was vaguely described as stretching from the east of River Indus to the west of River Ravi.

In time, the Dogra kingdom expanded northwards with the help of the British, who viewed it as a buffer zone against the ambitions of Tsarist Russia. Eventually, it took the shape of Jammu and Kashmir as it existed in 1947, with Ladakh becoming a part of it.

Until 1834, Ladakh existed as an autonomous kingdom. However, it faced invasion by General Zorawar Singh, acting on behalf of the Dogra king of Jammu. In 1846, following the formation of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), Ladakh was incorporated into it.

In 1947, around the time the Dogra Maharaja of the time, Hari Singh, hastily signed the Instrument of Accession, Pakistan gained a foothold in eventually became Gilgit-Baltistan, leaving Kargil and Leh for the Indian State forces to capture.

Ladakh became part of the autonomous state of Jammu and Kashmir within the larger Indian State. Around this time, Tibet came under the control of the People’s Republic of China.

This gave rise to a complex political matrix in Ladakh. The Buddhists of Ladakh felt marginalised within the Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir dominated by ethnic Kashmiris. They also felt neglected by the Indian State.

They felt that their unique geographical and climatic conditions were often overlooked, economic resources were not fairly distributed, and there was inadequate representation of Ladakhis in state and national institutions.

Over the years, there have been several protests and demands for Ladakh to separate from Jammu and Kashmir state due to ongoing marginalisation. People have called for the establishment of local institutions that prioritise the development needs of the region.

Ladakhi Buddhists did not also want to participate in the movement in Kashmir and parts of Jammu province to either join Pakistan or form an independent Jammu and Kashmir. They felt that this conflict between the people of Kashmir and the Indian State had created unnecessary repercussions for them as well.

Ladakhi Muslims shared some of these concerns of marginalisation and neglect, but they were more reluctant to have a future separate from their Muslim co-religionists.

The Ladakh Buddhist Association (LBA) has spearheaded a movement advocating for regional autonomy and Union Territory (UT) status for Ladakh.

After years of struggle, it was acknowledged in the early 1990s that the people of Ladakh should have the power to determine their own future. However, the demands were not comprehensive. The grievances mainly focused on the slow pace of development, unequal distribution of resources favouring other regions or religious communities, and inadequate funding considering the vast size and sparse population of Ladakh.

These concerns did not necessarily challenge the conventional approach to development or prioritise environmental and cultural preservation.

In negotiations with the Union and state governments, the Darjeeling Gorkhaland Hill Council model was considered. This led to the enactment of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council Act in 1995 (LAHDC), which was later replaced by a similar law in 1997.

This law aimed to grant Ladakh a significant level of autonomy. Initially, it was intended for both Leh and Kargil districts, but Kargil rejected the proposal. However, a few years later, Kargil established its own council in 2003, following the example set by the Leh district.

While the decentralisation process proposed by LAHDC-Leh suggests a potential shift away from centralised decision-making, significant challenges persisted. All council plans had to be approved by the state government and align with the Union government’s five-year plans, allowing for potential rejection or alteration by the State.

The development model envisioned by the council remains largely conventional. Although the Act grants the council executive power to implement schemes for district development and economic upliftment, there is ambiguity regarding its ability to independently define ‘development’, despite mentioning consideration for unique geo-climatic and locational conditions.

Moreover, there is no indication that traditional governance systems were considered for recognition or inclusion. The traditional decision-making system centred around Goba was completely disregarded at the inception of LAHDC-Leh, delegitimising local systems and excluding communities that followed traditional practices.

Additionally, while the council’s formal structure accounts for the representation of religious minorities, provisions for representation based on occupation, class, age, and gender are either lacking or minimal.

However, on August 5, 2019, the Union government decided to revoke the special status of Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. As a result, two new Union territories, Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, were established.

Following these events, sections of the Ladakh society celebrated its new identity. However, this joy has turned into resentment over the past five years as citizens yearn for the protection of their jobs and land which was initially guaranteed under Article 370.

One of the foremost issues gripping Ladakh today is the push for its inclusion under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution. The Sixth Schedule provides for the administration of tribal areas to safeguard and uplift the rights of the tribal population by providing them autonomy to preserve their culture and identity. It comes under Article 244(2) and Article 275(1) of the Constitution.

Other than the Sixth Schedule, issues such as environmental degradation caused due to proposed projects, lack of ecological protection and lack of political autonomy have caused continuous protests in the region over the past few months.

Not addressing the Sixth Schedule demand

The Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, currently in effect in parts of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Tripura, governs the administration of tribal areas in these states.

Under this schedule, district and regional councils, composed of elected and nominated members by the governor, have the authority to legislate on various matters including land use, forest management, irrigation and grazing.

However, laws related to marriage, social customs and public health fall outside their jurisdiction. With Ladakh’s tribal population exceeding 97 per cent, it fulfils the criteria for Sixth Schedule status.

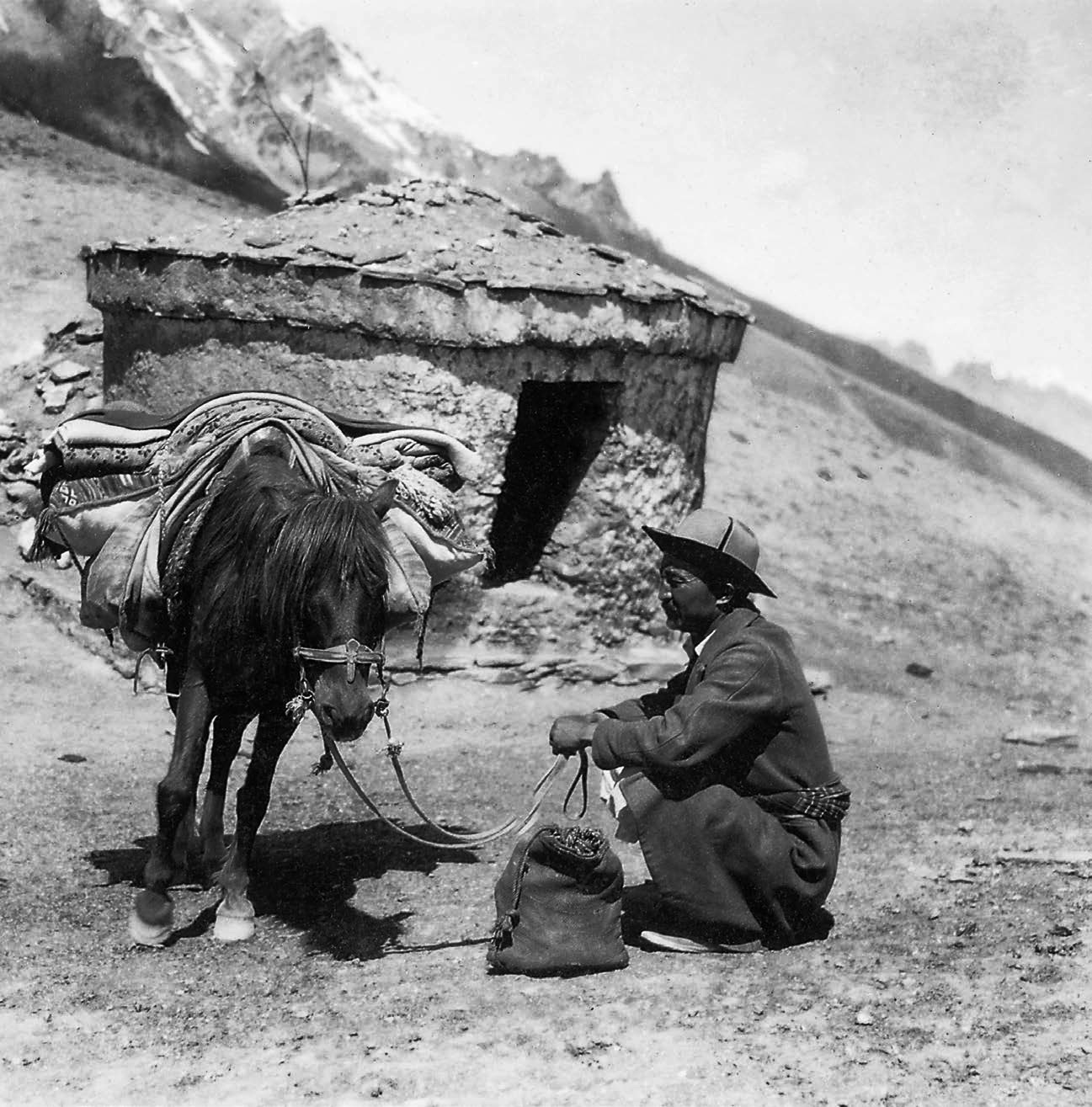

KL image: Bilal Bahadur

In 2019, the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes recommended that the Sixth Schedule be implemented in Ladakh. However, it was not implemented. Moreover, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) had promised to implement the Sixth Schedule in the region if they win the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council elections in 2020.

However, following the BJP’s victory in 2020, there was limited progress in fulfilling the promise to implement the Sixth Schedule. Despite the Kargil council passing a resolution advocating for statehood and Sixth Schedule protection, no advancements have been made under the BJP administration.

On January 2, 2022, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) formed a High-Powered Committee (HPC) for Ladakh’s development. Despite clear local demands, the committee failed to address the request for the Sixth Schedule.

Consequently, the committee was rejected by the Leh apex body and Kargil Democratic Alliance. Despite subsequent meetings attended by Ladakh leaders, the government of India remained steadfast in its refusal to accommodate the two main demands: Sixth Schedule status and statehood.

Subsequently, in January 2023, Union Home Minister Amit Shah established a committee to explore the Sixth Schedule status for Ladakh, but local groups rejected it for overlooking their concerns, including the demand for Sixth Schedule recognition.

Environmental degradation in Ladakh

Ladakh comprises over 90 per cent of India’s Trans-Himalayan bio-geographical zone. It hosts a diverse range of endangered species such as wild yaks, snow leopards and black-necked cranes. These animals play vital roles in the ecosystem and sustain indigenous communities for generations.

In the four years before 2019, only four memoranda of understanding (MOUs) were signed between Ladakh and private and public sector companies to establish projects in the region. However, in the past two years, over ten MOUs have been signed to establish various industrial units in the region.

These initiatives include an agreement with the government-owned Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) to establish India’s first geothermal power plant in Puga Valley, known for its natural hot springs, situated approximately 170 km from Leh.

This endeavour requires drilling up to 500 meters into the ground to harness naturally occurring hot water, which will then be utilised to generate electricity through steam.

Furthermore, another MoU has been signed with the National Thermal Power Corporation to establish India’s first green hydrogen mobility unit. This facility will employ renewable energy to split water into hydrogen and oxygen using electrolysis. The hydrogen produced is anticipated to power five hydrogen-fuelled buses in and around Leh.

In addition to these agreements, proposals are underway for the construction of seven hydropower projects along the Indus River and its tributaries. Furthermore, bids have been solicited for solar projects, while the Ladakh power development department has applied for clearance to utilise 157 hectares of forest land for constructing electricity transmission lines.

In Pang, a village situated 180 km south of Leh, there was a proposal to set up a solar grid that would require 20,000 acres of land in the cold desert.

Karma Sonam, a field manager with the Nature Conservation Foundation, told the Scroll.in that since discussions about the project began, there have been rumours that officials were trying to convince pastoralists to take up employment at the proposed solar grid.

“These people will be employed as labour in the grid, and their lives will be destroyed,” Karma Sonam asserted.

“The number of projects that have decided to come in post-2019 is incomparable,” Tsering Dorje Lakrook, a former member of the LAHDC, told the Scroll.in.

During his tenure as a member of the elected body from 2005 to 2010, Lakrook noted that “not a single private company” had approached the council to establish operations in Ladakh. Only a few government projects had been initiated during that period.

In the same interview, Konchok Stanzin, a councillor from Chushul and a member of the LAHDC, mentioned that most of the land that will be acquired for the proposed project will be grazing lands used for pasture.

“The possibility of individuals being compensated for the lost lands also does not arise,” said Stanzin. He also raised the concern of long-term effects that might arise due to changes in land use of the region along with the issue of dumping of solar debris.

The Tibetan gazelle, a species native to this region, is on the brink of local extinction, and such a substantial change in land use would make their existence even more precarious.

The grazing lands are also crucial for the pashmina or cashmere goats, whose wool is utilised in crafting the renowned pashmina shawls. In Puga Valley, where the ONGC was working on its geothermal project, Karma Sonam reported an instance of geothermal liquid leaking into the Puga stream, causing severe pollution in the fresh streams of the region.

Black carbon deposits

Studies have revealed that the glaciers in the Western Himalayas, which serve as the primary water source for Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh, are melting rapidly. This acceleration in melting is attributed to the increasing presence of black carbon aerosols and greenhouse gases, causing the snowpack in the region to darken.

A recent study assessed approximately 77 glaciers in the Drass basin of Ladakh using satellite data from 2000 to 2020. The research examined glacier shrinkage, snout retreat, ice thickness changes, mass loss and velocity alterations.

Results showed a 1.27-meter thinning of glaciers in the Drass region during the two decades. Researchers attribute this accelerated melting to elevated regional temperatures and increased black carbon levels from 1984 to 2020. Earth scientist and glaciologist, Shakil Ahmad Romshoo, has emphasised the direct correlation between black carbon and glacier melting.

He explained in the Scroll.in that black carbon deposition on glaciers diminishes their reflectivity, fastening the ice melt. Additionally, elevated black carbon concentration in the atmosphere amplifies radiative forcing, accelerating snow cover and glacier melting.

Proximity to the National Highway in the Drass region exacerbates glacier melting due to vehicular emissions’ increased black carbon concentration. The surge in Ladakh’s horticulture sector, driven by economic benefits, contributes to increased black carbon levels through the burning of orchard tree branches and woody biomass for heating.

Despite advancements in understanding glacier behaviour, key knowledge about black carbon’s impact on glaciers remains limited.

In a related study, particulate matter (PM) data from 2012 to 2017 revealed high PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations in Srinagar, Kashmir, surpassing national air quality standards during autumn and winter. Romshoo highlighted the valley’s haze during these seasons, exacerbated by biomass burning, which settles on glaciers, exacerbating melting.

Romshoo proposed converting orchard tree branches into high-calorific wood pellets to reduce deforestation and black carbon emissions. Shrinking glaciers in the Indus basin pose long-term threats to downstream communities, affecting water resources critical for Pakistan as well. The transboundary nature of these rivers underscores the potential security implications for South Asia.

Unregulated tourism threat

Unregulated tourism also poses a significant threat to the sensitive region. It was highlighted that during the 2020–21 season, Ladakh received four lakh tourists, surpassing its population of about three lakhs.

This uncontrolled influx exceeds the region’s ecological capacity. Incidents of tourists displaying disregard for the environment, such as driving into ecologically sensitive areas like the world’s highest motorable road at Umling La and the shores of Pangong Lake, have sparked outrage among the locals.

The situation may worsen with the planned expansion of the Leh airport. The Airports Authority of India announced a new terminal to accommodate 20 lakh passengers annually, significantly surpassing the current capacity of about nine lakh. “We want to have a say in managing tourist inflows,” Karma Sonam emphasised.

“Ladakh felt neglected by the Jammu and Kashmir state government before it transitioned into a Union territory,” stated Ashish Kothari, an environmentalist and co-founder of the non-profit Kalpavriksh in an interview with Times of India. “The region’s needs were consistently overlooked, leaving Ladakhis feeling underrepresented in the state’s bureaucracy.”

Autonomy in Ladakh

The main concern for the people of Ladakh is not the nature of the projects introduced by the Union government, but rather their exclusion from the decision-making process.

“We are not opposed to solar energy or other development projects,” explained Lakrook to the Scroll.in, “But we want a say in where and how large-scale projects are implemented.”

Even before the termination of the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, the council never attained the autonomy it sought upon its formation. “The LAHDC Act, 1997, provided some powers, but these were subject to approval from the state government in Srinagar,” explained activist-researcher Shrishtee Bajpai to the Scroll.in.

Bajpai’s 2019 study reveals that only about 10 per cent of Ladakh’s allocated budget was under the council’s control, with decisions in crucial sectors made without council involvement.

Since 2019, the council’s limited autonomy has further dwindled, with the Union territory’s administration increasingly interfering in its work, Lakrook observed.

Contracts and planning roles are often given to outsiders, and proposed policies don’t involve local voices and leaders. Despite promises of protection, Ladakhis feel insecure about their land and resources.

A new direction?

Ladakh’s special constitutional status should grant powers to the Kargil and Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Councils to control land, minerals, tourism and development.

Villages in Ladakh should also be empowered under the Fifth Schedule, alongside the Sixth Schedule, allowing for local self-governance through the application of the Panchayat (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act,1996.

This is crucial for the people of Ladakh to directly shape their present and future, given that over 90 per cent of the population are Scheduled Tribes. Additionally, the Scheduled Tribes and Other Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 should be promptly implemented to empower local communities, particularly those reliant on ecosystems for their livelihoods.

Without these safeguards, the government risks undermining the long-standing trust of the people of Ladakh in India and their vital role in border security.

Ladakh stands at a critical juncture, grappling with multiple challenges that demand urgent attention and proactive measures from the Indian government.

(Swati Gowri Shrikha Javvaji is an aspiring lawyer with a passion for dance and classical music. Her interests include politics, policy and public international law. She is an intern at The Leaflet. The report was republished as part of an arrangement with The Leaflet. The original report was published here.)