by Muhammad Nadeem

Despite theological differences, common ground is found in messages, the Gospel, Jesus’ miraculous birth, wisdom, signs, ascension, and expected return. Interfaith dialogue, exemplified by Muslim scholars, highlights shared spiritual foundations, emphasising obeying God’s word.

To comprehend the significance of Jesus’ life, it is crucial to grasp the socio-political dynamics of his time. The Roman occupation of Judaea brought about a stark dichotomy -the mighty Roman Empire versus the resilient Jewish people. The Jews, staunch monotheists, struggled under foreign rule, giving rise to diverse responses among them.

Roman oppression prompted varied reactions, from collaboration with the Romans by the aristocratic Sadducees to the nationalist fervour of the Zealots, who openly opposed foreign rule. Amidst this tumult, the concept of the Messiah gained prominence—a figure from the line of David who would liberate the Jews and establish a kingdom of peace.

As Jews hoped for a saviour, messiah-wannabes, such as Judas of Galilee and Simon bar Kokhba, emerged, each leading rebellions against Roman rule. Jesus of Nazareth was born into this milieu, hailed by followers as the Messiah. However, the question arises: Why did Jesus’ followers persist as a religious community, while other messianic figures faded into history?

While some scholars suggest Jesus was merely a failed militant rebel, the New Testament presents a different narrative. It depicts Jesus not only as a political figure but as a charismatic teacher and miracle worker. His teachings focused on faith revival and moral reform, left an indelible impact on his disciples.

The circumstances leading to Jesus’ crucifixion remain shrouded in ambiguity. His trial before the Sanhedrin, where he was accused of blasphemy, raises questions about the legitimacy of the charge. Crucially, the crucifixion itself, a Roman form of execution, suggests Jesus’ perceived threat to the status quo rather than blasphemy against the Jewish God.

The resurrection narrative, though a matter of faith, finds a mention in non-Christian sources. The account by the Jewish historian Josephus, while subject to historical scrutiny, acknowledges Jesus as a wise and virtuous man crucified under Pontius Pilate. The fact that Jesus’ disciples continued to follow him post-crucifixion adds an intriguing dimension to the historical Jesus.

In unravelling the historical Jesus from the layers of religious interpretation, we encounter a man whose life intersected with a turbulent period in history. His teachings, moral principles, and enigmatic identity continue to captivate minds and hearts. Whether viewed through the lens of faith or historical analysis, Jesus of Nazareth remains an influential figure whose legacy transcends the boundaries of time and belief.

The aftermath of Jesus’s crucifixion presented a profound challenge to his followers. In the evolving landscape of the nascent Christian movement, two prominent figures, James and Paul, emerged as influential leaders, each shaping Christianity in distinct ways.

Some disciples, including Peter, contemplated returning to their previous lives. However, a resilient community, known as the Jerusalem Church, led by James, the brother of Jesus, defied this temptation. The Jerusalem Church, comprising the twelve disciples and other believers, formed a close-knit community dedicated to practising and spreading the faith. Their activities, documented in the Acts of the Apostles, reflected a commitment to piety, communal living, prayer, and preaching the Good News.

Despite being acknowledged as the ultimate authority on matters of doctrine, James’s image remains somewhat blurred in Christian tradition. The Epistle of James, attributed to him, emphasises a theocentric rather than a Christocentric perspective, focusing on devotion to God and obedience to His Law.

In contrast, the apostle Paul, initially a persecutor of Christians, experienced a transformative event on the road to Damascus, leading him to develop a distinct theology that emphasised faith in Christ over adherence to Mosaic Law. After independent theological formulation in Arabia, Paul’s tension with Judaizers, who insisted on adherence to the Mosaic Law, became a significant issue. The Jerusalem Council in 50 CE, led by James, addressed this by establishing limited rules for Gentiles, yet scholars question the apparent harmony, suggesting a deeper tension between Paul and the Jerusalem Church.

The execution of James in 62 CE marked a pivotal moment, possibly tied to his opposition to exploiting poorer priests. The fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE dealt a blow to the Nazarenes, who, fleeing to Pella, later faced expulsion during the Jewish revolt in 132–135 CE.

Early Christianity saw the emergence of James and Paul, whose theological differences shaped the movement. While James maintained a theocentric, Jewish-rooted faith, Paul’s independent theology prioritised faith in Christ and distanced itself from Mosaic Law. Theological disputes and the fall of Jerusalem solidified the divide, enabling Pauline Christianity to dominate the Gentile world. The historical tension between James and Paul reflects the intricate development of early Christianity.

The year 610 marked a pivotal moment in the history of the Arabian Peninsula, where in a quiet cave near Mecca, Muhammad (peace be upon him), a forty-year-old merchant, experienced a transformative encounter. This ignited a movement reshaping the region’s religious landscape, exploring Islam’s roots, ties to Judaism, and historical expansion.

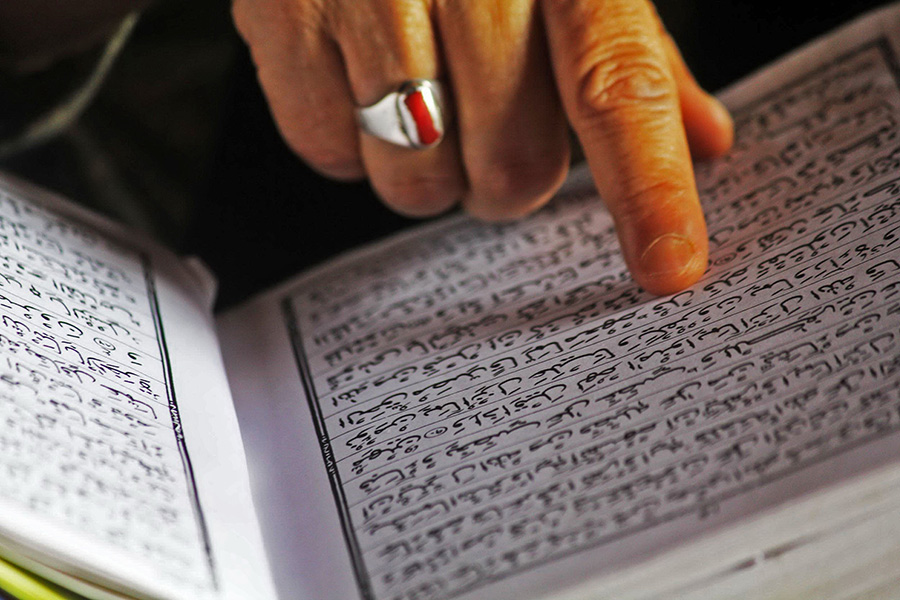

The Qur’an, condemned inequality and emphasised monotheism. Mecca’s deviated Ka‘aba, hosting over three hundred idols, fuelled Muhammad’s spiritual quest. The Qur’an identifies Islam’s God with Judaism, honouring the Children of Israel. It claims monotheism predates Judaism, extending to nations through unidentified prophets. Contrary to misconceptions, Islam sees Muhammad as a messenger conveying ancient truths, not a new religion’s inventor.

Islam spread, from Spain to India, prompting historical inquiry. Scholars like Fred M Donner argue it began as a sincerely religious movement for personal salvation. The Qur’an embraces monotheism, fostering religious coexistence. Islam’s spread doesn’t rely on forceful conversion, exemplified by positive relations with Christians under Heraclius and Caliph Umar.

Shared monotheistic doctrines, rejection of a trinity, and a legal framework highlight similarities. The Qur’an addresses Jews and Christians, urging true monotheism without excess.

Islam’s connection to the Abrahamic tradition, rooted in monotheism, bridges faiths. It emphasises shared values, rejects excesses, and shapes a global religious continuum. Understanding its historical context illuminates Islam’s theological foundations.

The Qur’an emphasises the special status of Mary, the mother of Jesus, portraying her as a virtuous and honoured woman chosen by God.

The Quran highlights specific incidents from Mary’s life, such as the Annunciation, the Nativity, and her return to her people with the infant Jesus. It underlines Mary’s righteousness, her dedication to God, and the miraculous aspects of Jesus’ birth. The mention of events like Mary’s sanctuary, the miraculous palm tree, and the spring of water draws attention to shared elements with apocryphal Christian texts, such as the Protoevangelium of James and the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew.

The Qur’an also addresses accusations against Mary. The reference to Mary as the “sister of Aaron” is elucidated as either a lineage connection or a metaphor to indicate her descent from a priestly family. The text makes Jesus disavow any notion of divinity for himself or Mary, stressing the importance of worshipping God alone.

The Qur’anic story of Jesus is concise compared to the New Testament. In the Qur’an, details like the temptation, preaching in Galilee, crucifixion, and resurrection aren’t present because Jesus isn’t the main focus—God is. Prophets are highlighted, with Rasul meaning the one who is sent and Nabi meaning the news giver.

In praising Jesus, the Qur’an uses Christian theological concepts but with distinct meanings. Jesus is referred to with numerous honourable titles. The term Masih is mentioned open to various interpretations, such as God wiping sins off Jesus. Jesus, in the Qur’an, isn’t a founder of a new religion but a messenger to the Children of Israel.

The Qur’an mentions Jesus’ mission to resolve religious disputes among the Jews. He brings clear signs, a term used over 50 times, indicating divine proofs. Notably, Jesus creates birds from clay, a unique miracle, absent in the New Testament. The Qur’an also highlights a prophecy by Jesus about a future messenger named Ahmad.

Despite mentioning the Gospel, the Qur’an’s view differs from the New Testament. The Qur’an advises followers of the Gospel to judge according to their scripture. The disciples of Jesus, called hawariyun, have a positive image in the Qur’an, contrasting with the New Testament. The Qur’an features a unique episode where disciples request a heavenly table, resembling the Last Supper. (Sura 5:114)

Regarding the crucifixion, the Qur’an denies Jesus was killed or crucified. It challenges the claim made by certain Jews, asserting that it only appeared so to them. The interpretation of this statement varies, with some suggesting a substitution theory. The context of the verse involves a polemic against Jews who slandered Mary and boasted of killing the Messiah.

The Qur’an’s stance on the cross might find a precedent in early Christian Docetism, a belief that Christ only appeared to suffer on the cross. Some Christian sects, like the Ebionites, held views aligning with the Qur’an’s denial of the crucifixion.

Understanding these historical and theological nuances is crucial for a comprehensive view of the Qur’an’s perspective on Jesus. Other Muslim commentators took a second and less radically rejectionist interpretation of “appearance” arguing that Jesus was indeed crucified but he did not die on the cross. He rather secretly survived his execution, they suggested, despite his “appearance” of death. Ahmadiyya people take this line. They even believe that “after surviving the cross, Jesus moved to Kashmir, to live there and ultimately to die a natural death. Hence in the city of Srinagar, there is still a highly revered tomb of Jesus.”

Islam recognises Christ’s special role as the Spirit of God, differing from other prophets. Some verses in the Qur’an, especially calling Jesus Word and Spirit of God, suggest a higher status. Historically, some thinkers granted Jesus an exceptional nature beyond humanity. Meanwhile, the Qur’an rejects defining Christ as the Son of God or the God Son, finding this notion blasphemous.

Over history, some unorthodox Christian thinkers labelled heretics, also rejected Jesus’ divinity. Those deemed Arians saw Jesus as subordinate to God, more prophetic than divine. Later, Unitarians merged from the Reformation, upholding Jesus as Logos but not God. They denied core doctrines like original sin and the Trinity.

Accused of secret Muslim sympathies, Unitarian ideas scandalised much of Europe. However, Unitarians aimed to restore what they saw as early Christianity, not conspiracy. Their theology resonated with Islam’s view of Jesus as Messiah but not divine.

Despite theological differences, common ground is found in messages, the Gospel, Jesus’ miraculous birth, wisdom, signs, ascension, and expected return. Interfaith dialogue, exemplified by Muslim scholars, highlights shared spiritual foundations, emphasising obeying God’s word. The ethical teachings of Jesus align with Islamic principles, refuting accusations of plagiarism by attributing shared inspiration to the same divine source. The figure of Jesus is a common ground for fruitful dialogue with Christians. Zechariah, John, and Mary are revered in Islam, with Mary considered one of the best women.

(Ideas are personal)