by Rafique Khan

The fishbone got stuck in my throat and the trauma of that experience made that feeding my last meal of Kashur Gaad.

In Kashmir, off late, fish have been in the news. The larger reality is that the shrinking and dirtier water bodies are impacting the fish harvest on a consistent basis. Kashmir produces not more than one-seventh of the fish demand pegged at 150 thousand tons. Almost 100 thousand people across Kashmir depend on fishing for livelihood. Jammu and Kashmir water bodies cover an area of about fifty thousand hectares (192 square miles) and they have seventeen species of fish.

After going through these reports I conjured my own fish-related stories about Kashmir.

Story One

I do not eat fish, in particular the Kashur Gaad (Kashmiri fish). When I was a toddler, my father, a civil engineer, worked for the Jammu and Kashmir’s Public Works Department (PWD) in its Bandipore Division. The Bandipore division headquarters, with offices and residences for the staff, was a sprawling premise laid out as a British suburban compound. The compound was at the toe of a mountain range, high above overlooking Asia’s largest freshwater lake Wular.

The compound was near Sunarwan (meaning golden forest) village. The PWD compound also adjoined river Madumatti which originates in the high mountains above Bandipora and empties into the lake. At Sonarwan, Madumatti flows in rapids. The PWD workers had built a check dam on the part of Madumati to create a small pond. The pond was stocked with fish.

I am told in Sonarwan a village girl named Jani helped my parents to look after me. Apparently back in the 1940’s the fish was so abundant in the Sonarwan pond even teenagers could catch a fish with their bare hands. Jani had caught a Kashur Gaad in the pond, and baked it in her Kangari, the traditional Kashmir fire pot, for me. The fishbone got stuck in my throat and the trauma of that experience made that feeding my last meal of Kashur Gaad.

Years later, on a hike to the mountains above Bandipore, I learned that the Sunarwani pond is no more. That is a long and different story.

Story Two

A British traveller in a fish-related story narrates an example of oppressive rule in Kashmir. This is the period when the second Dogra ruler Pratab Singh came to the throne in Kashmir, after the death of his father, Gulab Singh. When Gulab Singh died the court astrologers prophesied that the soul of the dead Maharaja had migrated into a fish. To ensure the survival of the dead Maharaja’s soul, floating as a fish in the waters, Pratab Singh issued a decree prohibiting fishing in the waters of his domain. The British traveller describes seeing the aftermath of violating that decree.

Two peasants were caught fishing for their food in their river. For their punishment the men were tied to a pole, their hands tied behind their backs, naked above the waist, with the fish they had caught tied around their necks. They were left without food or water, with their catch of fish, to die as a reminder of the fiat of the autocratic power in Kashmir.

In Kashmir even now about a century and a half later, I understand, unauthorised fishing is still prohibited. A government permit is required to fish in the Kashmir Waters.

Story Three

This is from my personal observation, from another corner of Kashmir, in an alpine river valley named after the river that flows through it, the Wadwan river. Wadwan river transitions into a slower meandering waterway within the Valley floor as it descends from the high mountains where the river runs in high rapids. Wadwan river has fish. The catch is that fishing requires a government permit. To get a permit to fish a Wadwan valley resident requires a day-long hike to reach the government office to apply for a permit. Access to motorable transport is extremely limited in Wadwan. So for Wadwan residents, there is no fishing. For the ones who dare to disobey and fish, greasing the palm of enforcement officials with a little bribe gets the perpetrator off the hook.

There is a government-owned fishery in Wadwan. The Fishery, near a village named Brian, located in the geographic centre of the Wadwan Valley, is a visible landmark. The fishery compound office building, a structure made of brick with a tin roof, is totally alien to the local architecture, it sticks out like a sore thumb in the verdant Wadwan Valley. The fishery compound is enclosed by a metal fence. Within the compound adjacent to the office there is a pond. The pond has a channel connecting it to the Wadwan River. During the week-long stay in Wadwan, we saw no human activity at the fishery. The building was locked and the pond was an alga-infested hole in the ground. There are no fish in the fishery at Wadwan.

Story Four

One particular fish species, Trout, has made Kashmir one of the world’s major destinations for recreational fishing. Trout species of fish is a transplant from Europe brought to Kashmir beginning of the 19th century, AD 1899. Frank J Mitchel, a Scottish soldier of fortune ran a carpet-making workshop in Kashmir. Mitchel convinced the Kashmir authorities to import Scottish trout eggs. After a failed attempt the second consignment of rainbow and brown trout 10,000 eggs reached Kashmir. Released in Dachigam and other streams the imported trout flourished in Kashmir.

As per The Third Pole (website) an institution organized to understand Asia’s water crisis, the real attraction of the trout in Kashmir is in its habitation in the numerous snow-fed mountains. Two tributaries of river Jhelum – Sindh and Lidder – offer the finest trout fish anywhere in the world. But now, confirming the larger reality, The Third Pole notes that the trout are declining due to a blend of pollution, human intervention and climate change. Trout cultivation as of now, mostly is from fish farms; government-run (90 tons) and privately run fish farms (300 tons)

Story Five

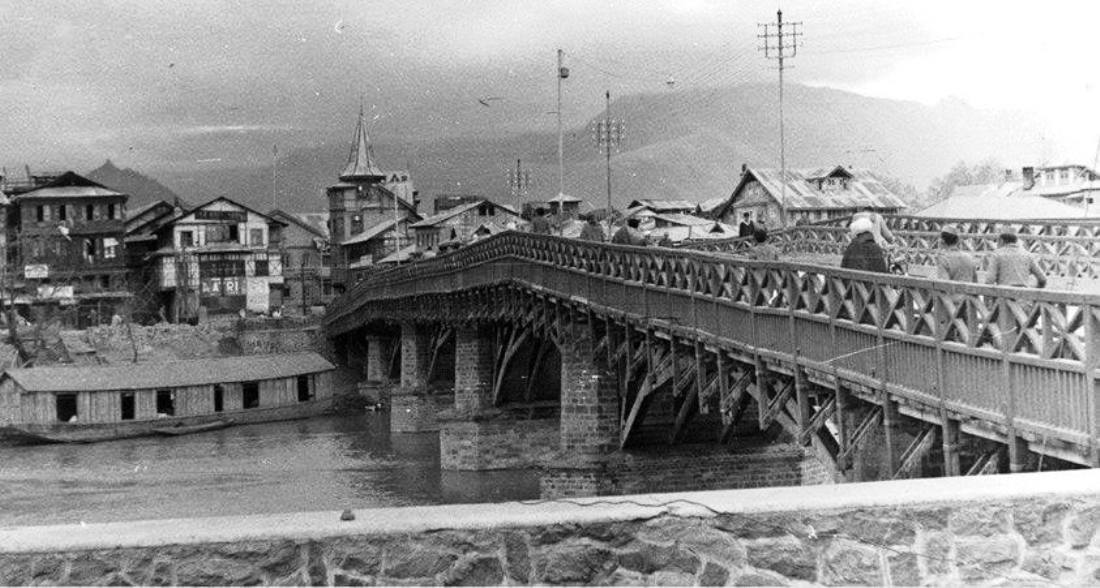

In the Summer of 2018, a friend and I went down river Jhelum in a shikara from the outskirts of Srinagar to the bank of Wuler Lake at Sopor. In our eight-hour ride we saw the degradation of the river. River Jhelum was once the main venue of Kashmir’s natural and cultural environment. River Jhelum is now turning into an open sewer. We saw every town and village on its bank open drains discharging raw sewage. It all empties into Wular.

We traversed Wular lake at dusk. A vast expanse of calm water surrounded by distant snow-capped mountains is a wonders sight. At Wular water flow is very gentle, so sediments in the water drop to the lake bottom. In Wular in the centre of lake, miles from the nearest habitation, I sensed a faint smell, a smell of sewage. Alas, I realized then that Wulur – Asia’s largest freshwater body – is turning into a sewage soakage pit. How will the Kashmiri fish and the people who depend on it for their livelihood survive?

Story Six

Now a story of my imagination.

Enterprising Scotsman Mitchel in 1900 AD envisaged and then worked to realise his vision to propagate trout fish from Scotland in the waters of Kashmir. Now Kashmiri entrepreneurs transport live fish from Kashmir, for expatriate Kashmiris to partake in their Kasher-Gaad and for the finest dining establishment to serve Kashmir’s Rainbow Trout, the premier trout in the world. And the best part is, it is all a private grassroots cooperative enterprise of Kashmiri young men and women.

How did this happen:

It started in Sonarwan, Bandipora. The year 2023 graduating college students from the Bandipora Degree College formed a co-operative society, Bandipora Enterprise Society (BES). The aim of BES was to facilitate enterprises for its members, mostly freshly minted college graduates. One BES member, a resident of Sonarwan, came up with the idea of rebuilding the fish pond on Madumati. Fish Eggs and baby fish were easy to pick from private and government fish hatcheries. Within a few years, the yield was good enough to supply the fishmongers in Bandipora.

As the word spread, many other fish ponds cropped up and down Madumatti and other areas of Kashmir. The main valley of Kashmir, where river Jehlum flows has side valleys, 24 in all. The valleys are drained by alpine tributaries like Madhmati that descend from the snow-fed slope of Pir Panjal and the Himalayan Mountain to join river Jehlum. Taking a lead from BES other Kashmiri young men and women from the 24 side valleys started their own fisheries.

And then other entrepreneurs got in the business to export the fish from Kashmir. For the Scotsman Mitchel back in 1900 it was as audacious task and took months of toil to bring his trout catch to Kashmir. In 2047 it would be a matter of hours for the Kashmiri fishmonger to fulfil orders of fresh fish to any part of the world.

It was not all easy though. Remember the government edicts on fishing in Kashmir, no fishing without permit. The BES members had to tussle to overcome the debilitating colonial legacy. The hardest part was to change their own colonial mindset. They had to change their thinking; they had to evolve from being passive subjects in an unrepresented old colonial regime. They had to evolve as votive citizens and take responsibility for their own being, and their existence. One of these responsibilities was to assume custodianship of their home.

The fish pond was one measure of their responsibility. BES canvassed and sought support from Sonarwan and surrounding communities, making the plea that the fishery would provide jobs for residents and generate local tax income for the betterment of local public services. The fishery would make BES vested to ensure the protection of the Madumati headwater from water pollution and soil erosion and thus conserve and enhance Bandipora natural environment. The community gave its support and the community support paved the way for clearing government administrative hurdles and getting the seed money to seed the Sonarwan Fishery, and many others like it.

(Author is a Los Angeles-based Kashmiri-American city planner. He manages the Kashmir Foundation of America. Views are personal.)