by Muhammad Nadeem

Over nearly 200 years since its invention, Braille has been adapted to work with over 125 different languages. This requires mapping the symbolic representation in Braille to the printed version in each language. Most visually impaired people who read Braille achieve a reading speed comparable to average sighted readers of print, around 100-200 words per minute with practice.

Enabling visually impaired people to participate fully in a literate society has been an important goal for many years. One key development that supported this goal was the invention of the Braille writing system in the early nineteenth century. Braille allows visually impaired people to read and write through touch instead of vision, by representing letters and words using patterns of raised dots on paper.

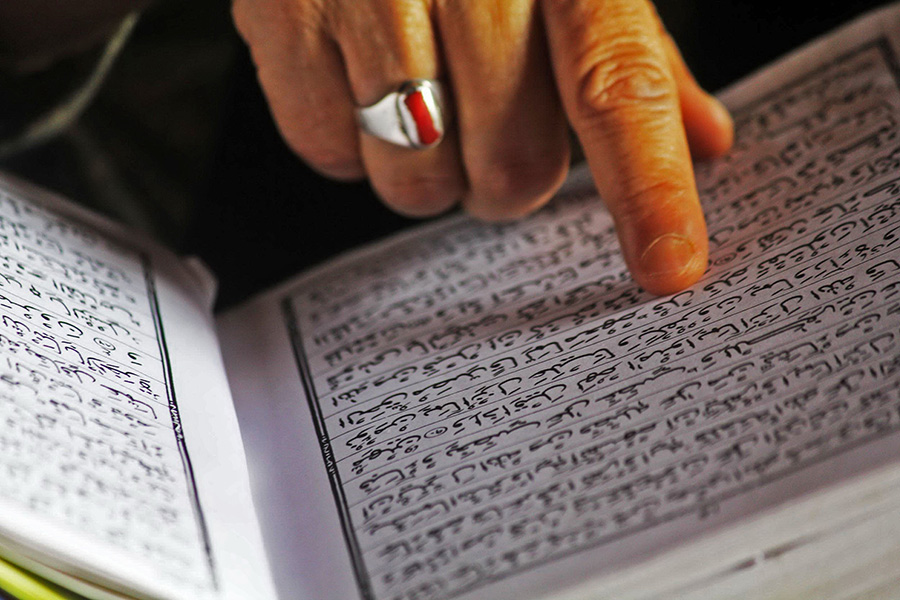

Over the last two centuries, Braille has been adapted to work with many different languages around the world. This includes Arabic, which is used to write the Islamic holy text of the Quran. However, translating the Quran into Braille poses some unique challenges compared to other texts in Arabic or other languages. This is because the Quran has special rules and vocalisations, known as vibrations, that affect how verses are read aloud. These vibrations are essential to convey the precise meaning but have not been fully incorporated into previous Arabic Braille translation systems.

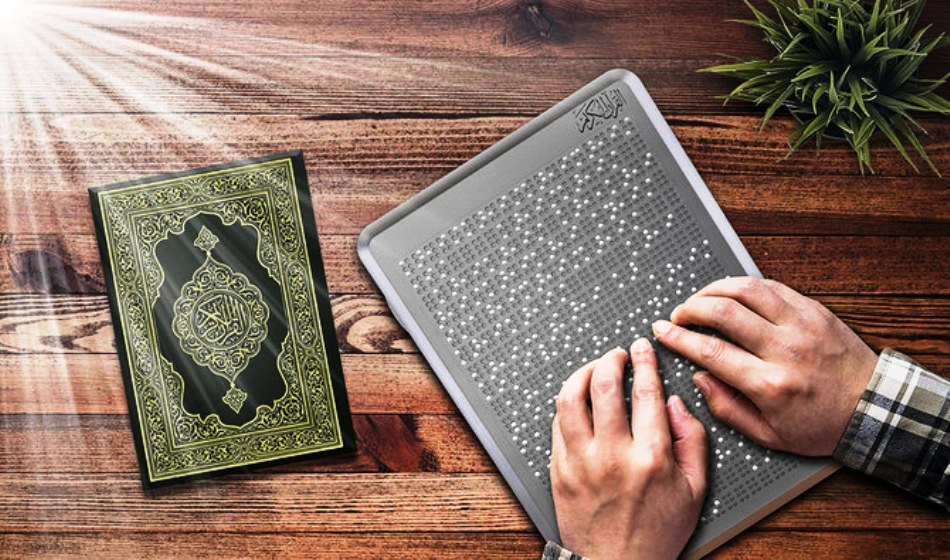

The Quran, basic to millions of Muslims globally, is revered as Allah’s word, revealed to Prophet Muhammad. For the visually impaired, Braille versions facilitate access, employing raised dots to replicate Arabic letters and diacritical marks. This meticulous process, using specialised paper and printing techniques, mirrors the printed Quran format.

Braille Qurans cater to varying proficiency levels and include translations and audio recordings. Skilled transcribers produce these versions, distributed freely by various Muslim organisations.

Carefully chosen Braille fonts like Uthmani ensure an authentic reading experience. Global organisations, including those in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, India, the UK, and Pakistan, contribute to Braille Quran production.

Overview of Braille

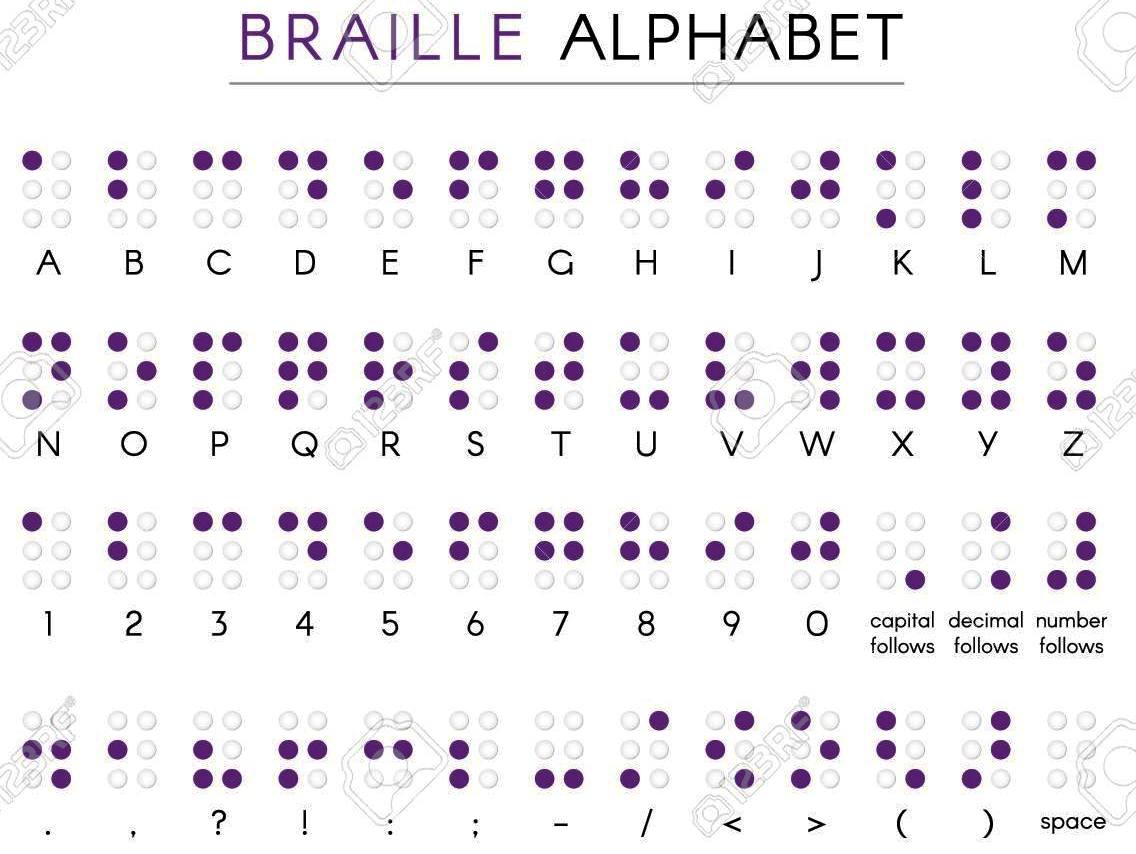

The Braille system was first invented in 1821 by Louis Braille, himself visually impaired from a young age, based on an earlier “night writing” system using raised dots created by Charles Barbier to allow soldiers to read messages by touch. Braille’s key insight was to simplify Barbier’s approach of 12 dots down to 6, arranged in a cell of two columns by three rows. This cell forms the foundation to represent letters, numbers, punctuation, and other symbols using specific dot patterns within the cell. For example, the Braille pattern ⠚ represents the printed letter ‘k’.

With six positions that can each be either dotted or not, there are 64 (2^6) possible dot patterns available in each cell. This turns out to be sufficient to map the necessary symbols of written languages. As well as symbol representation, various formatting like capitalisation and bolding can be added, and contractions can reduce the space needed for common words. Grade-1 Braille uses a one-to-one mapping of printed to-Braille symbols without contractions, while Grade-2 adds special contractions to reduce repetition.

Over nearly 200 years since its invention, Braille has been adapted to work with over 125 different languages. This requires mapping the symbolic representation in Braille to the printed version in each language. Most visually impaired people who read Braille achieve a reading speed comparable to average sighted readers of print, around 100-200 words per minute with practice.

Quranic Recitation

The Quran, written in Arabic, has some special phonetic features and rules that do not occur in normal Arabic text. Correct recitation requires pronouncing these specific sounds, known as vibrations when reading aloud from the Quran. Six common types of vibration found in Quranic verses are:

Edgham – Merging two letter sounds

Iklab – Pronouncing a noon letter clearly

Ikhfa’ – Pronouncing a noon letter unclearly

Idgham– Merging two noon letters

Edhara – Pronouncing tanween clearly

Kalkala – Pronouncing a letter followed by noon clearly

Strict adherence to these vibrations helps convey subtleties of meaning. For example, iklab and ikhfa’ differentiate words like “light” (نور nur), which should be pronounced clearly from “fire” (نار nar) which should be softened. Hence among scholars of Quranic recitation, it is vitally important to pronounce these vibrations correctly from memory.

Therefore, past systems for representing Arabic Braille, while working well for normal Arabic text, lack symbols and rules to handle Quranic vibrations. Developing solutions specifically for Braille targeted at the Quran could enrich accessibility for visually impaired Arabic readers to perceive these recitation features in written form.

Quranic Braille System

To address this limitation, research was conducted on developing an improved technique: the Quranic Braille system. This focused on detecting and translating the special Noon vibrations, building on an existing base Arabic Braille approach using a finite state machine model with custom translation rules. Hence readers missed some subtleties compared to sighted readers of the printed Arabic text.

Theory Building

The core translation process uses a finite state machine, moving between states based on the input text and configured transition rules and actions. Candidate text is processed one character at a time, checking matching translation rules depending on the state. When a rule matches, this outputs the Braille symbols updates the state, and moves to the next character.

Rule tables control permitted states and specify Braille outputs. For Quranic Braille, custom rules were added to output symbols for the special Noon vibrations detected in input verses. As no current Braille symbols existed, the first step involved selecting unused dot patterns to assign to Quranic vibrations like edgham(⠜) and kalkala(⠡).

The system stores a mapping of Arabic text characters to their standard Braille counterparts to enable lookup during translation. Additional entries were added to cover the newly defined vibration symbols.

The core system handles progression between translation states, getting rules based on the current context, checking input against potential rules, and then emitting Braille counterparts for matches.

Experimentation

The system was tested against a variety of sample Quran verses exhibiting different vibration types in various word configurations. Output formed the complete Braille dot sequences for each test verse, including successfully representing the Quranic vibrations. The analysis confirmed accurate translation supporting the enhanced rule set.

Conclusions

This research presented a new system tailored for translating Arabic Quranic text into Braille, meeting the specific need for representing essential vibrations used in reciting verses. This helps address a limitation around conveying the full context available to sighted readers compared to standard Braille Arabic approaches. Experimental results demonstrated successful translation covering a variety of test cases.

Potential future opportunities exist to expand support for additional Quranic vibration types beyond the initial Noon case. Adapting to related languages like Jawi with similarities to Arabic writing could also increase accessibility for visually impaired readers of texts in those languages, as many share Quranic characters and conventions.

This Quranic Braille project developed both custom computational techniques and new Braille vocabulary to help visually impaired Arabic readers perceive textured nuances around reciting verses from Islam’s holy book. Moving forward, wider deployment of such tools to generate embossed output could enrich engagement with the Quran and deepen understanding or memorisation among visually impaired Muslims worldwide.