The months that Omar Abdullah spent in confinement are far less than the years’ Sheikh Abdullah did. Then why did Omar grow a beard unlike his grand-father, Haseeb A Drabu goes on a hair raising exploration linking Kashmir’s politics with individual outlook and tradition and history

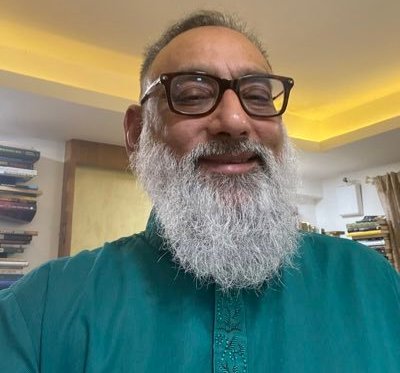

Omar Abdullah’s beard, which he wears post his incarceration, received a lot of attention, especially on social media. For more than a moment, it was the beard and not the person wearing the beard that was the centre stage. Indeed, an online poll was conducted on it.

The picture that got leaked to the social media spoke a thousand words. Needless to say that in the spiteful world of social media, it generated thousands of comments. Not that all were acerbic. In totality the complete range of emotions was evoked; from the angst of the supporters to the disdain of his detractors; from the empathy of his friends, especially of the page 3 kind, to the sadistic pleasure of his foes. Not to talk of the trolls!

The attention in the media and social media was only on the appearance; how he looked. Not one commented on what it meant. Not only was growing the beard a statement; the woollier, scruffy style made it an even bigger statement.

Political Message?

There is definitely more to his beard than mere looks; the symbolism seemed to have been missed. Could it be a political message that he wanted to send? Or was it reflective of an ideological shift?

Or was he, like a Milan Kundera’s character, trying to identify and look like a PSA detenue, the law under which he was booked, to deal with absurdity. Like Kafka’s famous Joseph K, Omar was picked up for an unidentified crime! Maybe he was just being bone lazy. Maybe. Maybe not.

There is a well-deciphered politics of the facial hair. Apparently, men who are public figures often change the way their face looks during the epilogue of existential upheaval. The appearance of a beard in the midst of a monumental change has been termed as an “existential beard”. The reasons and psychology behind this are many.

For sure, Omar Abdullah must have gone through an existential crisis during this period. It couldn’t have been easy on the poster boy of yesteryears mainstream politics. The beard that he grew during incarceration was an overt and obvious reaction to his incarceration. So for starters, it is an existential beard. Is there more to it?

It would seem so. This kind of beard is an unconscious device to reassert status after a setback. So say Christopher Oldstone-Moore, considered to be an authority on beards. As such, the beard displays his intent to reclaim, rather than an indicator of regret. So here we go; it is an existential beard which is long on intent but short on repentance. They may not be remorse but surely the dominant saltiness of the beard would suggest anguish.

Omar’s beard may, in fact, be an attempt to redefine, even reinvent, his image. He is presenting a different self – older, saner and wiser. Though not many people will grant him, it can even be classified as a personal act of political resistance; of course well within the boundaries of his existing political predilections. It is an out and out political beard.

The most likely impetus for Omar’s beard is to demonstrate a break from the past. And resurface with a fresh motivation having learnt some lessons the hard way. How and when he will do this, if at all, is not something that face-furriers spend time and energy on. That is for political analysts to decipher and predict. Of course, on the face of it, literally and metaphorically, a beard is a matter of personal choice, more often either a sign of lethargy or a signal of vanity.

Beard In Kashmir History

But beards do signify a lot more than personal style; from counter-culture defiance preference to political ideology to a religious obligation. It is not just the preserve of radical and communists.

Yet, a beard and its norms rarely exist outside of a broader cultural context and considerations. In the pre-modern era, a beard connoted influence and high status. As such men pressed into servitude were often shorn of their beards as a sign of subjugation. Nearer home, more recently, in Afghanistan, a man could be jailed if his beard is not long enough!

During the 1930s and 40s, wearing a beard was the norm in Kashmir. The weather and the wherewithal being important reasons for it. By and large, Kashmiris would wear beards that were inclusive of the moustache. It is somewhere around the 1950s, that the Anglo Saxon culture of shaving as a norm for social propriety seems to have influenced Kashmiris. It resulted in the practice of wearing a beard as a routine feature to being postponed until after Hajj, the Mecca pilgrimage! In Kashmir, everyone would surely wear a beard on return from the pilgrimage.

A pluralist society with long-standing traditions of liberalism, beards in Kashmir was not seen as the sine qua non of being a devout Muslim. Nor being clean-shaven of being less of a Muslim. Either way, it was not a big deal.

By 1990s, however, beards were back with a bang. With pogonophobia – an extreme dislike of beards – being displayed by the security forces, it came to become defiance and youngsters starting wearing beards with a vengeance in Kashmir. But with an important difference from the past culture.

In the 1930s and 40s, and even till the 1970s, it was, by and large, a sign of religious piety. Post-1990, it became a sign of political sway. Beard now indicates an ideological leaning. It is not just a matter of appearance.

Today beard, not just in Kashmir, but all over the world has been appropriated by the Salafists who wear their beards long leaving their upper lip clean-shaven. These beards have come became a symbol of the fundis (short form for fundamentalists) within the Muslim community. It is a sign of times that we are condemned to live in. Abraham Lincoln with his no moustache scraggy beard would have been trolled as a jihadi Islamist!

In the Kashmir of today, a beard, more than being a sociological signifier, has become a political reference point. It is a short-hand meant to indicate who you are dealing with and what they are all about before they even speak.

Given this socio-political context, no wonder Omar was trolled on his new look; more on the style of the beard than the beard per se. The refrain “Omar Singh”, is directly drawn from the style of his beard.

Omar Abdullah apart, with the abrogation of Article 370, the valley seems to have turned into a follicle farm. Why did the political class become hairy all of a sudden after August 5, 2019? What began this trend, and what fuels it? There is an easy answer, though it leads to harder questions.

Sheikh’s Imprisonment

The face fur that Omar carries these days was cultivated in 33 weeks of political incarceration at Hari Niwas. Going back in time, the eight months he spent in confinement, nazar band, as it used to be called evocatively, is less than the number of years Sheikh Abdullah spent in jails across the country. In one stint, after he was dismissed as the Prime Minister in 1953, he was in jail for an entire decade.

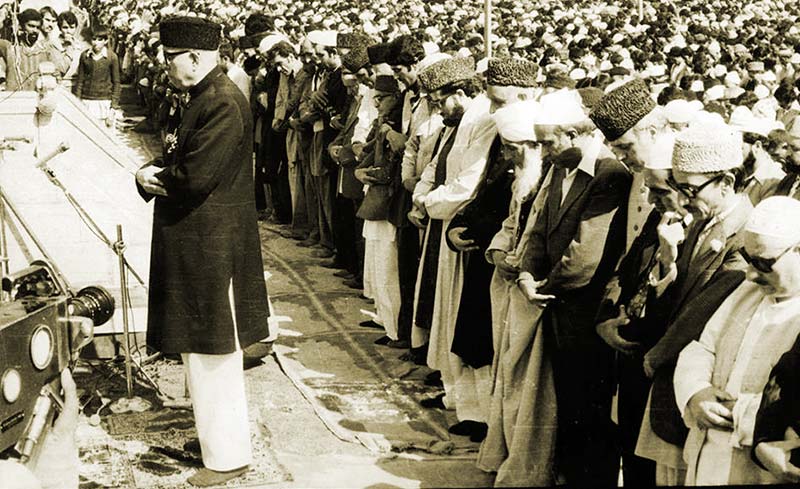

Yet, and this is interesting, Sheikh Abdullah never grew a beard in incarceration. Be it in Ootacamund, the back of beyond Tamil Nadu, or nearer home at Kotla Lane in New Delhi or at home in Srinagar. Wonder why? It would seem very natural. Not only was he a rebel or seen as a rebel. By their very existence, beards and rebellion go together.

He was also believed to have been a devout practising Muslim. Local political folklore has it that he once kept Prime Minister Nehru waiting at the Char Chinari while he offered his evening prayers there.

In fact, he leveraged religion for his politics as no one has done before or for that matter after. The way he used Muslim Auqaf Trust and the revered shrines of saints in the valley is unparalleled.

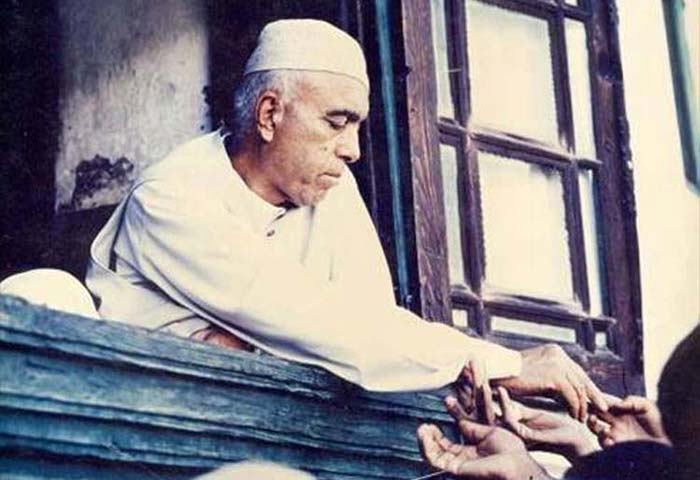

I remember seeing his photographs, sitting at the window of Dastgeer Sahib at Khanyar giving Tobruk to devotees! Space and a privilege reserved initially for the progeny of the saint and later for the managers of the shrines, the ubiquitous babas!

Hazratbal, of course, was his political backyard. He even used the pulpit there for the political propagation of National Conference. Pather Masjid was the place where he started his political career.

All these facets point to the fact that the requisite ingredients – a cause, a circumstance and a commitment – were all there for him to grow a beard. Why didn’t he? Not just during his periods of incarceration or during the height of his political popularity. What makes it interesting is that in the 1930s when he started his politics, he did have a beard, albeit briefly. That, as was pointed out above, was the norm then. What gives?

Semiotics would suggest that the reason for not sporting a beard was an act of political branding. In as much as there are political reasons for having a beard, there are also sound political reasons for not having a beard!

Bakra Beards

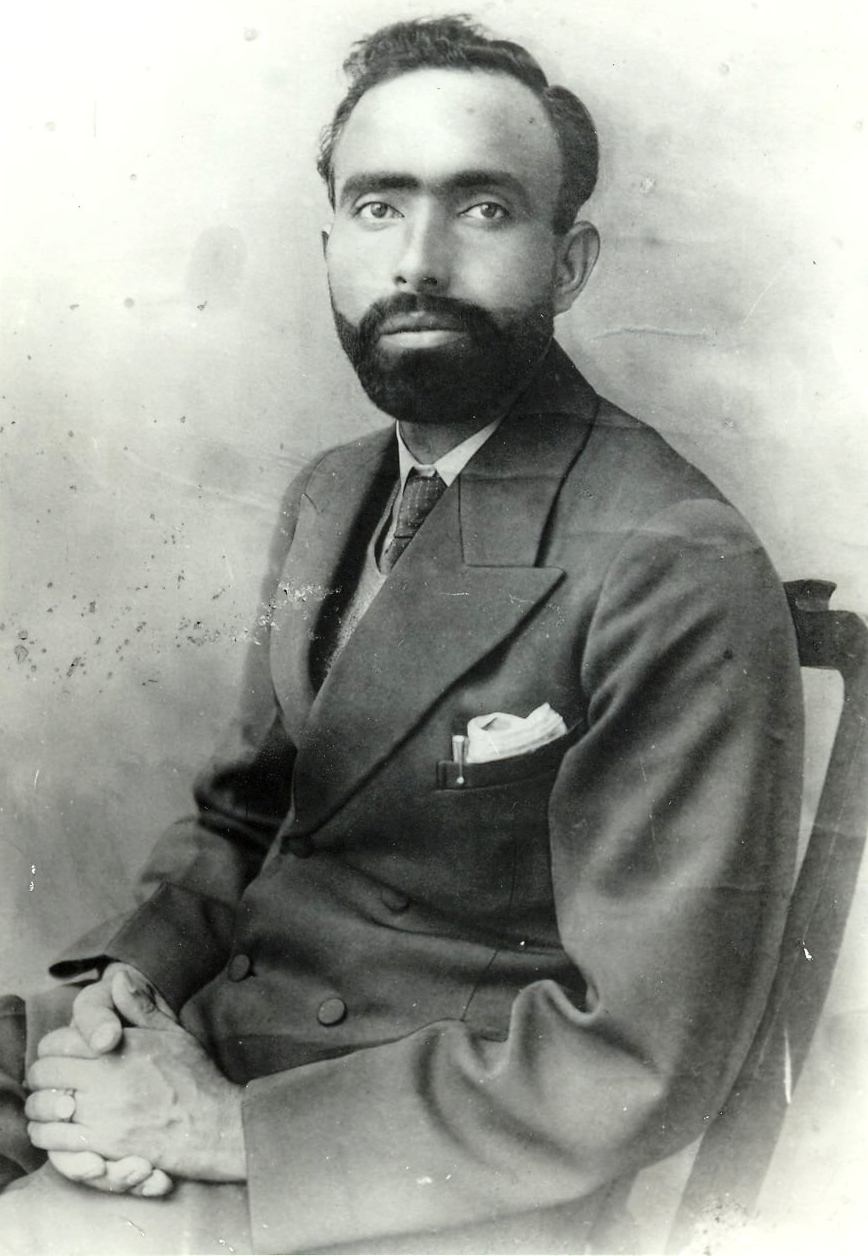

Politically, in the mid-1930s, beards were associated with the bakras, the main political competitors and adversaries of Sheikh Abdullah. By virtue of their religious position as the chief cleric, the Mirwaiz and his followers were obliged to sport a beard. It was their identity marker in many ways. The then Mirwaiz, Molvi Yousuf Shah, fresh from Deoband, had set up his own political party, the Azad Conference in 1933 to counter the Abdullah threat.

When pitted against them as adversaries’, Sheikh Abdullah positioned himself directly as well as in a nuanced manner. Besides, his major assault on them, he also playing on a simple natural antagonism. He propagated the derisive term bakras for them in relation to himself, the Sher! Earlier, during the time of Molvi Rasul Shah, the Mirwaiz clan was nicknamed and derided as Yezar Pirs by the Kashmiri orthodox mullas. Sheikh Abdullah made them bakras with the central wordplay being the goatee; a beard form! Thin on the cheeks and long at the chin.

It is here he differentiated himself in visual appearance from the Bakras. He shaved off his beard of social norm and made a political differentiation by not having a beard. In his case, the relevant symbol was of not having a beard rather than having a beard. So there was a politics of the beard; or of the non-beard!

Clean Shaven Politics

It seems to be an old tradition that politics and facial hair do not get along well in Kashmir. No wonder then, despite beard an integral part of the civil society of Kashmir, there has not been a single bearded Chief Minister so far! Or for that matter even a Governor!

The political demarcation by beard continues in Kashmir even today. Every single separatist politician has a beard. Be it Syed Ali Geelani, Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, or Yasin Malik. On the other hand, most mainstreams leaders, as a rule, don’t have beards. This takes us back to what we started from: the beard of Omar Abdullah! Has he crossed over? If only the beard could tell!

Tail Piece

The image and political power of a beard are exemplified by the greatest political beard that was attached to a gentleman named Fidel Castro. That beard was a symbol of challenge to the American imperialism. In what has to be seen as a tacit acknowledgement of the political power of the beard, Uncle Sam deputed the CIA to get rid of Castro’s beard and make him feel “politically naked”! The CIA spent considerable time, money and effort to medicate his cigar so that he loses his facial hair! In one of the many failed attempts, they infused thallium salts in his cigar to make him shed his beard making him lose his image which had become synonymous with his beard!

(Author is an economist and a former editor. He was also the finance minister of erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir state. Ideas expressed in the write-up are personal.)