Despite Shariah providing for remarriage options for a missing person’s wife after four years, a mix of legal and social hurdles are hindering the prospects of many young half-widows. Rights groups are seeking a pro-active role of clergy to ameliorate the problem. Aliya Bashir reports.

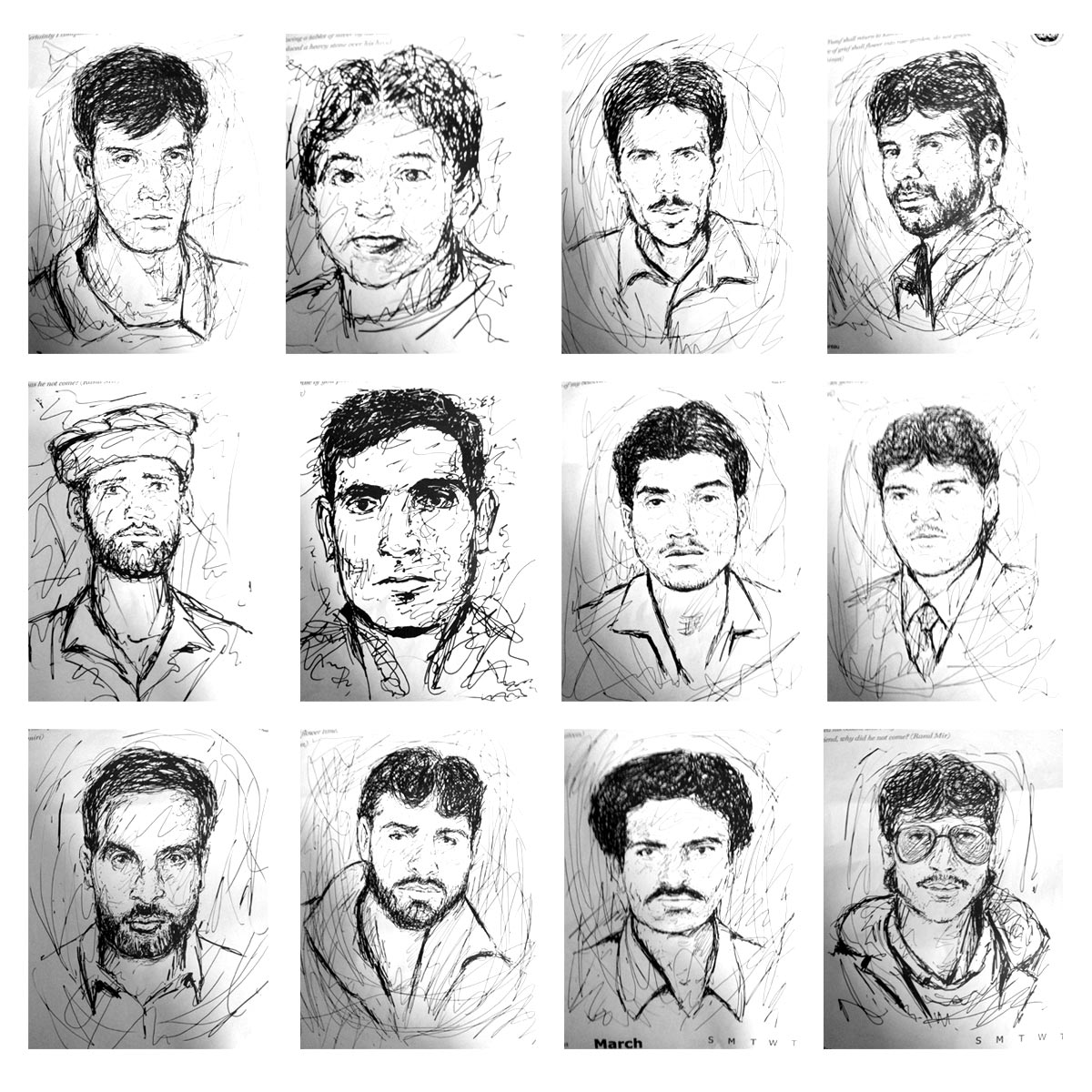

(Members of Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons holding a silent protest demonstration in Srinagar on Friday. (Pic By: Bilal Bahadur))

Gulshan (name changed), a resident of Baramulla district is a half-widow – a term given to a woman whose husband’s are missing after being allegedly picked up by troops. It is five years since his husband left for work in the morning to never return. She has no news of him, not even an idea of what happened to him.

Tired of tracing her beloved, she wants to move ahead, at least to take care of herself and her three children. Off late she is thinking of remarriage – for moral and economic support.

“You can’t make a caged bird sing,” Gulshan laments. “Life has crushed me with a double tragedy, one of my husband’s disappearance and another to look after my children especially their education”.

Her in-laws have warned her against remarrying, and even if she takes a stand, there are legal hurdles too, that ask for a seven-year wait period for a missing man’s wife to be eligible for remarriage.

Even then there are others who haven’t been able to remarry after 10 years of their spouse’s disappearance. The responsibility of children, property rights, and other social factors act as the main barriers.

Sara Begum, a resident of Nowgam, Srinagar, a nurse by profession waited for 12 years for her husband’s return. In her mid 30’s, finally, she married her husband’s nephew. “Everyone opposed my decision. But I had children to feed and no one helped me during the turbulent years of my husband’s disappearance,” said Sara, while recalling the ‘tribulations’ from her in-laws. “I faced every kind of pressure, both from the in-laws as well as the society. I never succumbed. After remarrying, I have no regrets. In fact, many a time I regret why I didn’t remarry before”.

Interestingly, the Shariah (Islamic jurisprudence) provides for a four-year wait for remarriage in such cases.

The Srinagar based civil rights group, J&K Coalition of Civil Society (CCS) organized a conference of Islamic scholars on August 30, the international day of disappeared. The conference titled “Half Widows and Orphans – A way forward in Islamic Jurisprudence” brought together Islamic scholars and social activists to debate the issue.

CCS head Pervez Imroz says the motive of the conference was to find a solution to the problems of half-widows, including those who want to remarry.

“Remarriage of young widows is definitely an issue. It should be debated and put into the limelight at a larger canvass,” Imroz said. “We will again try to invite religious scholars of Kashmir and consult the ulemas (Islamic scholars) of European countries to get their feedback over the issue. There has to be a consensus over the issue to end the pain of half-widows”.

Molvi Muhammad Yaseen of Baramulla, a religious scholar, who attended the conference stressed on the need of resolving the problems being faced by the half-widows. “We should understand the plight of the half-widows and think how they can be supported… We should try to develop a consensus so that we can initiate a step for helping these victims. There are debates and discussions always about the victims but there should be something practical,” Molvi Yaseen said.

Imroz lists the reasons hindering half-widows to remarry as property rights, children, and domination of their in-laws. “A half-widow is not allowed to take a decision at the individual level. Thus, she becomes a victim of clashes of the interest within the family,” he said.

Imroz says that there are 1500 half-widows in Kashmir with most of them in mid 30’s. Some, he said remarried after long waiting periods.

Half-widows mostly live with their in-laws. Many prefer to wait for their husbands and for others it is a jigsaw puzzle with fog of uncertainties.

They are not eligible for government compensation until they prove their husbands are dead.

Half-widows, unlike widows, are caught in a jinx whether to remarry or not. Their voice is buried in the political and social milieu as they are mostly not allowed to opt for re-marriage, given the reason of hereditary rights and the centrifugal force of their in-laws.

“Many a time, I thought of remarriage. A lot of people approached me but nobody was willing to accept my children. So I left the idea for the sake of my children,” says Tahira, amid sobs.

Tahira’s tumult started in December 2002, when her husband, Tariq Ahmad Rather left home for New Delhi. “My husband left for New Delhi in connection with his contract business. Before leaving, he told me that he will talk to me on phone, but that never happened, recalls Tahira. “I was staying with my husband, not with my in-laws. I informed my in-laws and sought their help in searching for my husband, but to no avail. Then we registered an FIR in the concerned police station.”

She says her husband’s disappearance is still a mystery for her. Her two younger sons live in an orphanage in Srinagar. The elder son lives with her in a rented room in Srinagar and studies in 10th standard. To feed her children, Tahira works at a local charitable organisation.

According to experts, the problem lies with the clergy and the society, who have a role to play in defusing the crisis faced by half-widows.

“To declare a missing person as dead, a Qazi shariah (cleric knowing jurisprudence) is needed. But they seem to be in a deep slumber as far this serious issue is concerned,” says senior journalist and rights activist Zahir-ud-Din. “This is the main reason for leading the half-widows into despondency.”

He said the half-widows are in a fix. “We call them half-widows, but they are not being given the rights they deserve. Neither do these women fall in any of the category fixed by various NGOs, orphanages and widow homes,” Zahir-ud-Din says.

According to the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939, later adopted by J&K in 1943, if the husband is missing for seven years, the marriage stands dissolved.

Senior advocate Zaffar Ahmad Shah says that the Act provides for remarriage of the woman under certain circumstances. “If her husband’s whereabouts are not known after seven years, a person is presumed to be dead. In a conflict zone like Kashmir, seven years seems to be a long period. But it is for the law to fix a shorter period, keeping in view the seriousness of the issue.”

As for the property rights of half-widows, Shah says, she can get her due share in her husband’s property once the court presumes her husband as dead. “I am also of the opinion that the law made by the State legislature should be amended. The seven-year term should be replaced by four years,” Shah said.

Most of the Islamic schools of thought agree that a four-year period of absence of a spouse should be enough to declare a marriage annulled and a joint consensus should be evolved on it.

President of the Jamiat-e-Ahlihadith, Moulana Showkat Ahmad termed the issue as a grave one. “If the husband of a half-widow returns after four years (after second marriage), first marriage will not remain intact,” Ahmad said. “Shariah has set different rights which need to be understood so that no space is left for confusions. Let there be a joint meeting of ulemas of all sects on the issue so that a consensus is evolved to resolve the problems of half-widows.”

Aga Syed Baqar-al-Mosvi, a Shia cleric and scholar hold similar views. “We have to obey religious Supremes (In Iran and Iraq) in order to have a consensus on this issue. We too believe that maximum period set for the remarriage of a half-widow is four years,” he said.

Grand Mufti of Kashmir, Mufti Bashir-ud-Din agrees.

“According to Islamic Shariah after four years and thorough investigation when disappearance is proved they (half-widows) can go to the court of Shariah and remarry,” says Mufti Bashir. “It is up to her whether to exercise her powers for remarrying anywhere she likes. She can sell and use her husband’s property for her maintenance. But there is no criterion for the division of ancestral property”.

Scores of half widows in Kashmir live in wretched condition, suffer psychological ailments and are more prone to attempt suicide. Many have fallen prey to depression, phobia, emotional instability and post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Many half-widows visiting the hospital are hypersensitive and show signs of depression. We treat them with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy,” said Sadaqat Rehman, Assistant Professor in Clinical Psychology, Government Psychiatric Hospital, Srinagar.

Activists say that awareness is the key to overcome social barriers that aggravate the problem of half-widows. For that they say, both activists and clergy need to play a pro-active role.