By Adil Bhat

Last night, a vivid and strange memory from the dawn of December 1999 crossed my mind. I was a little boy then, and had a huge fascination for both snowfall and sunlight. My mother would be the first one to wake up for the fajr (morning) prayers. And along with her, I would also move out of the comfort of the warm bed only to see the weather outside. I would peep from the large window on the first storey of my house. Sometimes the garden would be snow clad, reducing visibility to zero. This meant house arrest till the skies were clear. And there were times when there were signs of sunny day.

My days were planned according to the weather. Usually, the brilliant sunshine would automatically bring a wide smile on my face. But that day was a mild sunny one. Unlike other days, my mother came back to the room to lie down for a while after offering her prayers. While lying down, she spread her hands to embrace me, but couldn’t find me next to her. Hurriedly, she got up and ran down towards the staircase where she knew she would find me sitting close to the glass window, sticking my nose to it, making impressions with the dew on the windowpane and smiling to myself.

Wearing her white pheran, she came running down the stairs only to hug me and assure herself of my presence in the house. She said to me, “Muan gobur! (My child!), why do you come here every morning? I know you will be sitting here but still if I don’t find you on the bed I get worried. Every day I run down to make sure you are here. My heart palpitates at the thought of not seeing you here. I come to assure myself. And if you continue sitting here I will come every morning to embrace you close to my bosom. Muan Gobur! I love you and only a mother can know a mother’s love…”

She repeated the last line twice. With my round red-cheek resting on her one arm, I looked at her and asked with equal passion, “Mamma, what if you do not find me here?” This was the last time in my life that I ever asked her this question. She panicked and started weeping. As tears rolled down her cheeks, I got up and turned my face towards her to say, “Don’t cry. You will always find me here or next to you.” She held me close to her chest and took me in her arms to the warm bed.

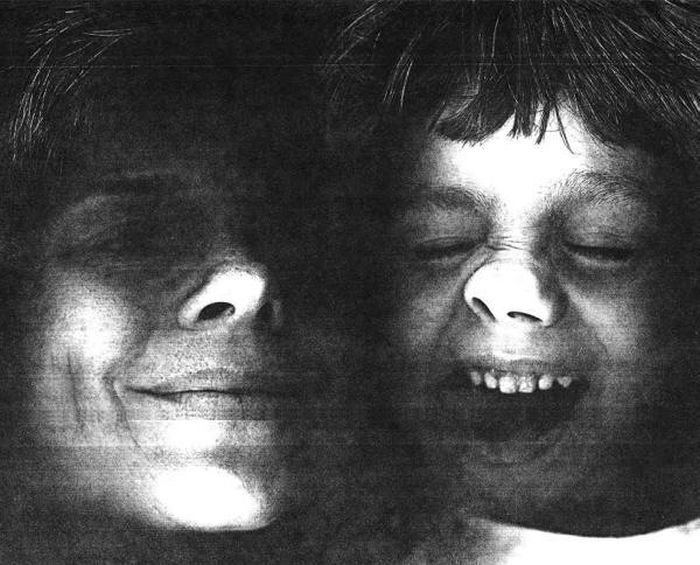

That day I knew the fear that runs in my mother’s mind. Every child in Kashmir knows this fear that their family goes through; the fear of loss, of absence, of no return.

If one goes around meeting the locals of the region, one would know the history of this fear. As I was growing up amidst the beautiful orchards and warmth of the hearth, I also witnessed several incidents of harassment at the hands of the army personnel stationed in the residential areas in the villages. These experiences were from my neighborhood. I still remember one chilling account of Hamid Gani Bhat, a young 21-year-old boy, who went to college, but never returned. What came back after a week was his disfigured dead body, bearing torture marks. This incident had a powerful impact on the psyche of the whole neighborhood.

The image of that day is still clear in my eyes. Hamid’s body lay in front of the door of his house. The villagers had gathered, listening to the roars of her mother, who was beating her chest while miserably crying, “Where should I get my child from? Why did you brutally kill him? Muan Gobur! Wake up, your mother is here.” It was thunderous.

I was standing beside my mother. I looked up at her and started weeping. I never cried aloud. I was a sulking child. I held the corner of her shawl and silently cried. The words “muan gobur” resounded in my ears. My mother had said them to me in the morning. I knew why she cried.

I ran inside the house and sat at the window, piercing my eyes through the glass. I saw a group of uniformed men, standing not very far from Hamid’s house. I knew who killed Hamid. There use to be conversations in the house during meals about such similar incidents occurring in different villages, across the valley. The stories of torture, death, brutality gradually became a part of our daily lives. That became the new normal. There were countless Hamids who were murdered, some disappeared forever, and some were recovered years later in mass graves.

With a new dead body arriving in any random house, I came to know the cruelty that the Kashmiri youth was facing then. Each year had a list of horrific stories. The distant neighbours shared similar fears. Distances were diluted with the anxiety that each one of us faced. I grew up in this environment of fear. There was no escape, but to live on. It was at the heights of violence that neighborhoods shrunk close together, sharing stories of their loss and giving comfort. I have grown up with images of violence around me, and so have all other Kashmiris. We share the same anxieties and fears.

From that mild sunny day of December 1999, I, along with my other compatriots, have travelled a long difficult terrain. I still go back home and sit close to that huge window and look outside with the same intensity as before. My mother has turned old. She doesn’t come down running searching for me. Now, I go back running to her when I hear her call “Muan Gobur!”

(Adil Bhat is studying English Literature from Delhi University)