A Short Story by Omair Bhat

Seasons bear a witness.

Silence has been reigning over our house from a decade, clinging to every inch of the run-down structure like life expunging spell bidden to dispel even colors of ruin from our lives. Life inside the structure is static skimmed upon the latches of doors closed from long years; cobwebs spun around them enmeshing latches into spooled labyrinths of fear and neglect. Structure, accursed by fate and denounced by holy scriptures – directionless, facing Qibla in no direction. Its rostrum sits on damp layers of dead leaves and loose soil.

A drab path graced by flat stone slabs sided by rough white-washed pebbles dug into earth loosely, wet with the mournful drizzle of dawn, leads to the entrance of house facing south. Half-baked vases moulded out into shape from black clay on the potters wheel with variegated designs and patterns at the base holding myriad rose offshoots – yellow, white, red-line up the portico; tiny rain drops on their withering sepals look like sliver coins tossed onto ash. Doused over long years an extinguished chiraag rests on the upper ledge, squatted, like a reminder of bygone catastrophe, its desiccant wick stiff as reed. Under the eaves of house sparrows huddled together fluttering their fluffy feathers, shudder as they peck on the crumbs of leftover from the over night dinner.

In the half-orderly Kitchen hung on the wall by a rusty nail an antique clock quakes fearlessly, in it three thin hands shrap as edged blades, snapping in regular pulses and sliding over each other in solicited intervals; as they struck to six in the morning they dissect clock into two half-moons – as snug as two teaspoons; above tied to a hook in the centre of ceiling an oversized bulb, in it faint incandescent crescent glinting – bulbous, dust and dirt settled on its obtuse surface overlooking the room like a curios – vacillates as the gentle blows of morning breeze lunges at it; outside in the lush of lawn damp with the overnight dew among clusters of irises in the flower bed broad petals of a solitary narcissi shine amber white with the rising of day. Three lean peaking cedars manoeuvring our courtyard, their outspread recumbent with frost, seem lording over our spartan house like an old grey haired matriarch – wrinkles working their way on forehead, smirks spread across the rumpled face. On the vestibule, surrounded by beige iron grilles wrapped in trumpet bindweed, stands she rubbing her palms hard against each other – soil coming off in thin, slender sickles exposing her white of palms; sun playing on her arching brow in complete submission. Struggling her way through mud to the backyard up to a well where on a creaking wooden pulley a steel pail sways and swings on a rope, she fetches her old dented utensils pulling the rope up briskly; moping the rill of well, washes her hands, thoroughly, and returns. Alert. Squelching sounds coming from beneath the feet as she stomps her way back from the well. As she walks in, soft-footed, into the house a crisp linseed fragrance wafts in, scaling the silence filled rooms and roaring through the dimly lit corridors.

Each morning, with the crack of dawn, when she wakes up thumping an alarm clock violently, after a brief stealth in bathroom, arranges and rearranges her sleek hair in front of a large square mirror that guards the wall facing its glinting reflective surface. She oils her hair that flows unending like mississipi up to her waist, extolling her slowly dying beauty.

“Mirrors scare me more, now, than reflections of past,” she says, grimaces gouging her disconsolate face as she stares into mirror.

__________________

Not after a week she bore me a fair skinned son she underwent a trauma. She was never to become mother again. Doctors, peering through their fat spectacles looking into her medical reports with unknown but furtive curiosity, had told me. Consoling me in a condescending tone. A flurry of nervous activity had swept over me. I had felt barrage of cold shivers running down my spine, earth sliding beneath my feet. I had felt pointed spines devouring my quiescent flesh beneath the skin and poison dipped needles raving my body, freely.

“If you can do me a favour, telling her all this by your own as I won’t be able to let her know this,” I had barely managed to say.

“… will let you know. Bring her here a day before you leave hospital,” descending his steps back into noisy corridors of maternity hospital, he had replied almost hurriedly.

________________

On the day when we were to visit doctors early in the morning sweltering sun – not fully swaddled in the clouds yet – had offered a grave profile through the veiled columns of fleecy clouds, perhaps, knowing the intensity of grief a stricken mother may hail.

“Nishi.”

“Yes, jenab,” she had answered smilingly, oblivious to what had befallen on her.

“Doctors wanted to have a word with you before we set back our journey homewards, about your health.”

“Yes, and why must it be that?” With a puzzled look on her face she had remarked, fiddling with her unkempt locks on her temple, her ever genteel gazes fixed at the fidgety movements of little creature lying in her lap, “I am fairly good.”

“How must I know? We still have to visit since we are leaving tomorrow.”

Silence, following up.

“We must hurry to doctor’s chamber. He must be leaving by any minute for routine rounds in hospital. Hurry, lady. Hurry.”

The clouds had disappeared. Sun was shining vivid dispersing its prismatic rays into countless ramifications. Light breeze stirring up the gaunt leaves outside on the arbour was blowing over small dunes of trash dislodging porous polythene bags from one place to other. In silence, we passed through the corridors before knocking at cabin door of doctor.

“Asalamalikum.”

“Wa-alikum salaaaaa..mm,” clad in white starched coat doctor had fumbled looking into reports, flipping pages nonchalantly, one after other.

“I would like to have a word with your wife, alone. If you don’t mind…”

“Please.”

“Here, Madame, in the corner, please.”

“Sure,” she had replied, baby Saleem fast asleep in her lap.

After she was back from the corner we kept looking into each others eyes, in grave anguish, for longest of the time. Her eyes wet, bereaving gaze hung like clang upon butcher’s knife. Running a fingertip along the rim of her eye she harvested a fat tear drop.

“I am sorry, for I didn’t know this would ever happen to me,” tears rolling down her cheeks incessantly.

___________________

Years altered the form, appearance and character of life. Saleem grew, irreconcilably; faint traces of beard conquering his innocent face. Nishi would often encourage him in the serene morning on his exam days, the same morning like this. She would stroke his head, pat his back asking if he is feeling well; if he has sharpened the pencil or if he has the geometry box – bought from stationary shop – in it all the instruments functioning smoothly, compass moving about on one point smoothly, margins of broad scale sharp as edge of scimitar, pencils pointed precise like spear – or, if he had the cardboard rinsed with a wet cloth on it date-sheet clipped like identity of consciousness. If he had slept well enough. If he would eat a little more, an apple or a glass of milk, more. And, to which he would react.

“I am no child any longer, ma,” squinting his eyes in an effort to express his irritation.

“You will always be a good little child in my eyes, buddu,” combing his hair Nishi would rejoin.

Memories have lasted, lives lost.

One sad day, crossing the shadow-speckled hush of early noon, young Saleem trot hurried steps through courtyard, sifting through narrow alleyways leading to his high school, never to return home back. On his way back from school, I was later told, he was frisked by Henchmen of Indian Army; hurled into one of the hunting green jeeps, kicked, thrashed upon resisting their oppression and carried away to some unknown torture centre. The chiraag had extinguished, then. Chirag of her eyes: Chirag of my eyes. We never saw him. Waited to hear from him for years. No jail would it have been where we didn’t search him in – Kot Bhalwal, Tihar, Ranchi, Gogoland, Rajasthan – nowhere, we found him.

____________________

Nishi would wander in his search – every alley. Her day would dawn with throes of morning and set with the siege of evening. Her eyes sank into rivers of emotions with every passing day. Every time she crosses the street Saleem was last seen she hears him hurrying home, offering pleasantries to elders passing by, sprinting this alley and that.

In our village, a madman donned in white soiled outfits – an accomplished surgeon in his time – with full array of armamentarium in front him tracing lines in dust with child like excitement with a pair thong, this diagonal intersecting that as if playing tic toe, annoyed by flies, often would fell into momentary reveries, humming.

“afsoos, your sons died on my table, blue veins erupted, arms amputated, who are you looking for in wood’s to return?” Laughing gruffly.

He had shouted at Nishi, once.

“Your son too, yes, should have writhed on one same table.”

She still looks for him. Not in the jails, anymore. But among unmarked graves. Thousands containing millions of Janana’s. Saleem thus became one among the many ‘disappeared persons’. Our janaan, a disappeared person. We have joined Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons, recently. We represent a community now. Community victimized by murderous struggle and barbaric oppression demanding remains of our hopeful dreams that once shone in our eyes.

___________________

She emerges in the Kitchen, places her utensils on a shelf, and seats herself on a stool, straining water from a mug into a glass.

A brimful glass of water. I fake a stoic smile. I tell her the water she has brought from backyard well tastes exactly the same as tastes the water from springs of Eden. Crestfallen, she stares a blank glance into my eye. Another. I resist its honeyed fragrance. She believes that every well, every brook in our village fetches the water of same taste as her – sweet, and fresh – which now, she rarely tastes. Every droplet of the water, as I glum down, is like her smile that flows dulcet from her face only when she smiles carefree. I smile. Her disheartening smile shrivels, in a moment. Fades. Like colours from a tunic. Bringing back to her memories of Saleem.

“Her minute, after noon, is night,” I mutter half-heartedly.

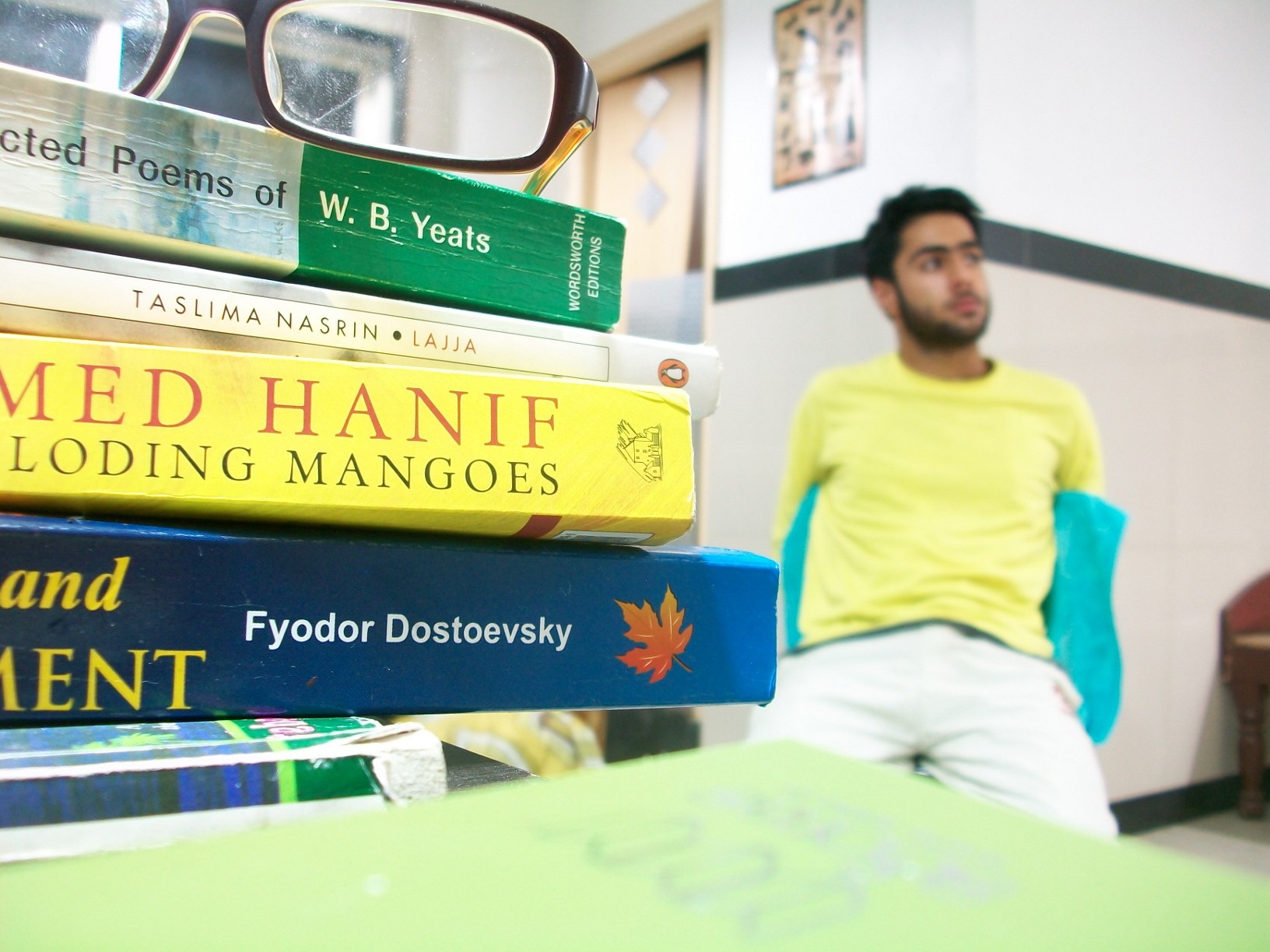

(A budding poet, voracious reader and an aspiring writer, Omair Bhat is a valley based paramedic student in Rajasthan)