How long do you wish your loved ones to live? A hundred years? At 132 and having never taken any medicine must be a nice feeling. Shams Irfan meets the man who has seen Kashmir most of us read about in books.

On the banks of river Lidder, hidden behind the tall concrete commercial hotels in picturesque Pahalgam is a small village called Manzimpora. But it’s not the village I am looking for. I am there hoping to meet a man who claims he was born in 1880.

It is easy to miss the entire village had I not known that a grand old man, 132 years, lives here in a small house. Even his little old dwelling, tucked amid a concrete jungle of commercial buildings, reminds one of an era gone by.

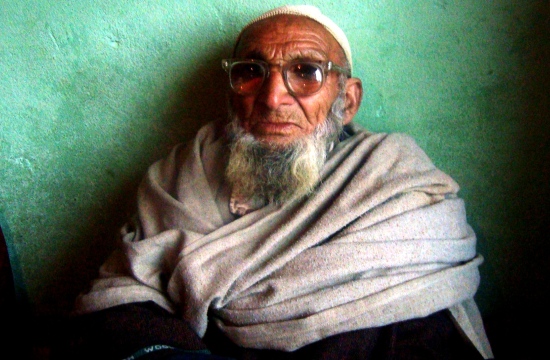

As I approach his house, I see a tall old man sitting on its small steps. Looking beautiful and healthy the old man is wearing a skull cap and thick glasses. He is Abdul Ahad Bhat, perhaps the oldest Kashmiri living. He is wearing a traditional Kashmiri Pheran and a shawl like cloth covers his shoulders. He watches patiently as the sun starts to hide behind the mountains. Balancing himself perfectly with a wooden staff, he started walking towards Lidder River, which touches the corner of his small kitchen garden.

“So you have come to see how old I am?” he asked while abruptly stopping near the edge of the garden. “Isn’t it enough that I am still alive?” he smiled. Abdul Ahad Bhat, who claims to be 132 years old, spends almost his entire day by the side of Lidder. “Since I was a child I liked the sound of water crashing on these big rocks. It is kind of soothing,” says the grand old Bhat.

Bhat is well aware of his importance as a witness to some of the most significant events in history in past century. “Had I known that I will live long enough to see this day, I would have definitely tried to save something from the past,” he says.

Bhat started his career as a peon at Lahore airport when he was around 25. He clearly remembers his days at Lahore airport and the people who used to travel during those days when air travel was afforded by a chosen few. “My best day of life is when I met Sir Mohammad Iqbal (Allama Iqbal) at Lahore airport. He was the humblest of creatures one could ever meet in life,” Bhat recalls.

Though he has little interest in politics, Bhat claims to have attended one of Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s rallies in Lahore. “I went just to see Jinnah Sahab,” he says. On another occasion Bhat claims to have met Mahatma Gandhi when the latter was on a visit to Lahore.

Bhat does not have any documentary proof of his age but with from his sharp memory he claims to have been born in 1880. When I asked him how he is sure about the year of his birth, he said, “I have learned from my father about my year of birth. He was good with dates and would keep record of almost everything.”

In the early days of the 20th century, when motorcars were very rare, people would travel long distances on horsebacks or on hired horse driven carts. But even these modes of transport were confined to rich and affluent only. People like Bhat had to undertake long journeys on foot. “It took me 21 days to reach Lahore from my home on a bicycle,” recollects Bhat. He remembers that journey quite vividly. “I left early in the morning from Pahalgam and after a day’s journey I reached Hazratbal shrine. From there the next day, after taking along some food for the journey, I travelled for next twenty days and reached Lahore on my imported bicycle.”

During his stay at Lahore, he says, he would travel to his native place every six-month or so, but in 1947, when he came to see his family, he was not allowed to travel back. Lahore was now part of Pakistan. “They asked for lots of papers in order to let me travel to Lahore,” says Bhat. “But I had none and lost my job.”

Since then, Bhat has made Pahalgam his home and spends his time rearing sheep and working on his small piece of land, growing maze.

As the sun finally sets behind the mountains Bhat started walking towards his house. Inside, it is pitch dark as both the windows are covered with cheap plastic and walls colored in dark green. Bhat settles himself down while flashing his new set of teeth in the darkness. “I have grown new teeth sometime back, they are no false ones,” he tells proudly.

After coughing vigorously for about a minute Bhat finally catches his breath to talk about his numerous journeys. “I have been to Ladakh to the point from where China starts and it took me exact 41 days to reach there on foot.”

Bhat claims to have travelled to Jammu, Chrar-e-Shrief, Baba Rishi (near Gulmarg), all on foot. “There was no other alternative. If one had to travel he would do it on foot only. Not all could afford horses,” he says.

Bhat married twice and has only one son from his first wife. “I got married late as I was in Lahore most of the time,” he says. “My second wife was from Ashmuqam. I used to go there every Friday on my horse to offer prayers.”

Ask Bhat about the secret of his long life and he won’t think for a second before replying, “I kneel five times before Allah and that is my only secret. I have hardly taken any medicine in my life. I can still walk miles on my own. It’s His gift and nothing else.”

Bhat feels that such a long life is both a blessing and a curse as he has outlived every single relative, friend and acquaintance of his. “Watching them all leave one by one is the most painful part,” he says with a hint of sadness in his voice.

Seeing his smiling face turn sad, I changed the topic and asked him about his memories of Maharaja’s reign in Kashmir. “I must have been around 10-years-old when Maharaja Pratab Singh was ruling Kashmir. But I clearly remember Maharaja Hari Singh’s rule.”

Closing his eyes to remember the times of Maharajas, he says, “During Dogra rule in Kashmir, Muslims were living in abject poverty as all officials were either Dogras or Pandits.”

During the early days of Dogra rule people were taken to as far as Leh and Ladakh on Begaar (forced labour). The system was later abolished during the reign of Pratap Singh. “When I was a kid my grandfather was taken by Maharaja’s troops to Rajouri for Begaar. But he managed to give them a slip and stayed in hiding at Banihal for about two years,” says Bhat.

For Bhat the worst ended with the exit of the last Maharaja as there is “no comparison to their atrocities”. “I was jailed twice for refusing to carry water for troops stationed at a police station,” he recalls. “We were all subjects and free labourers for them. Nobody was there to listen to our woes during Maharaja’s rule. Thank God it’s over,” says Bhat, touching both his ears with his hands, a typical Kashmiri gesture to express an extreme experience.

Bhat claims to have been part of the delegation that went to Amarnath cave with Maharaja Hari Singh’s wife. “I was with Maharani when she went to Amarnath shrine praying for a son,” remembers Bhat. “Even Maharaja Hari Singh would often visit Pahalgham with a caravan of ponies.”

But according to Bhat, Maharajas who ruled the princely state of Kashmir with an iron fist were ignorant of the plight of the masses. “They (Dogra Maharajas) would visit Kashmir like tourists and would often go back (to Jammu) in autumn.”

The frail old man feels that the instant rush of tourists in Pahalgam has affected the natives in a manner that is threatening their existence now. “They have turned the entire area into cemented jungle. There were hardly any buildings here. Only a few shops in the main market that too mostly owned by traders from Peshawar and Lahore,” he claims.

According to Bhat even the annual rush of pilgrims to Amarnath cave was limited to a few hundred only.”There were hardly any pilgrims before Kashmir came under India. It was all lush green and full of tall pines. Beautiful and virgin,” he reminisces.