by Sheikh Saqlain

SRINAGAR: Fifteen years ago, when my grandfather, a musicologist, despairingly hung his Santoor on the wall, little did I realise what our Kashmir, the Valley of Sufis, had lost. It is only now, when I have grown up, that I realise the hauntingly mesmerizing melodies of Sufiyana Mosiqi (music of Sufis), which Sheikh Abdul Aziz, my Lala Sahab, preserved by devoting his entire life, are rarely heard.

Kashmir has been a conflict zone for the past 30 years. The bullets and the bombs killed thousands. Those who escaped lived, but their spirits were torn apart, nothing to help, nothing to heal. After all, what could? The soul-soothing, mystic tunes of Sufiyana Mosiqi, the voice of God, were nowhere to be found.

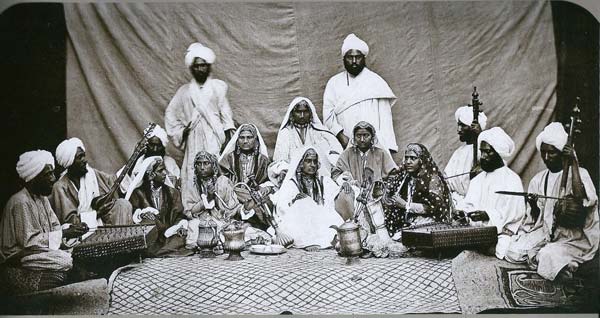

Sufiyana Mosiqi, a style of choral music performed by four to five musicians, each playing an instrument and singing, came to Kashmir from Central Asia. Having learnt the divine secrets, the mystics of Kashmir then moulded them into their own tune, nurtured the art and passed it on for hundreds of years until the beginning of the 20th century, when royal patronage began to fade away.

Since 1947, when Indian rule over Kashmir began, the neglect faced by Sufiyana Mosiqi has only reached new heights. As of today, Kashmir’s Sufiyana Mosiqui has lost 138 of the 180 ragas or melodies mentioned in ancient scripts, as well as some dances of antiquity. The tradition of verbally passing down melodies from generation to generation, too, contributed to the near extinction of this music form, like many other forms of art.

But, before his death in 2005, my Lala preserved the surviving 42 melodies before by notating them. Lala would tell me about his travels to remote villages and towns of Kashmir, of meeting old musicians and music-lovers, in search of Sufiyana ragas for his four-volume monumental musical notation, Kashur Sargam. “He fought this battle almost alone,” wrote Kashmir’s leading journalist, late Shujaat Bukhari in The Hindu newspaper.

Lala also authored music textbook Ramooz-i-Moosiqi or Secrets of Music, which deals with the grammar of Kashmiri music before he joined the ethnomusicology department in the University of Maryland – Baltimore as a guest teacher in 1988.

Not only melodies, Sufiyana Mosiqi also lost several indigenous instruments. Only the stringed santoor and the Kashmiri sitar, as well as the dhokra, a percussion instrument, remain.

The malaise has even touched dance. Hafizas or female dancers disappeared from the Kashmir cultural scene in the late 1940s when the dancers were linked to prostitution.

Strings of Hope

I have only had the privilege of listening to Lala through his recordings. Still vivid in my mind are Persian verses of noted Sufi, Amir Khusrau:

Ay chehra-e-zeba-e-tu,

rashk-e-butan-e-Azari;

Har chand wasfat mikunam,

dar husn az-aan zebatari.

(O Thou whose beautiful face is the envy of the idols of Azar (Abraham’s father and image engraver of antiquity); Thou remainst every moment superior to any praise of mine.)

But Lala was sad, I know. His damaged mulberry-wood Santoor, its strings broken forever, tells me. So does his diary.

“Sufiyana music was never encouraged by Indian cultural agencies,” a note reads. He wrote that the dance from even Manipur, India’s tiny north-eastern state, receives more help from New Delhi. “Why not Kashmir?”

But there is still hope – Mohammad Yaqoob Sheikh.

Sheikh, 58, a working performer at Radio Kashmir also teaches students the art of Sufiyana at the Qaleenbaaf Memorial Sufiyana Music Institute. He founded the institute in 2004 amid violence and political strife, but his courage and passion have kept it going through the years.

Because of the popularity and ease of availability of other forms of music, finding students who are passionate about Sufiyana is difficult. Finding students who are willing to put in the effort to master the art is even more difficult.

But Sheikh keeps it going. At his institute, his disciples are engrossed.

Saqiya bar kheez darde jam ra.

Khak bar sar kun ghame ayam ra.

(O Saqi pour the wine into the glass, throw dirt on the days of sorrow)

(This write-up appeared at ourlostparadise.com. It is being used with permission)