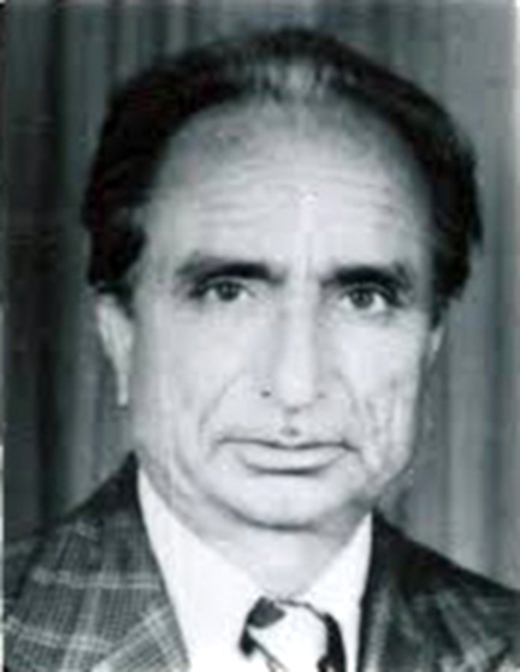

One of Kashmir’s most respected writer-intellectuals, Akhtar Mohiuddin (1928 – 2001) has used multi-disciplinary techniques for exploring the distant past to understand the evolution of Kashmir as a pluralistic culture. Muhammad Nadeem read his book posthumously and reviewed it

In his book, A Fresh Approach to the History of Kashmir, Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din (d 2001) embarks on a thorough re-examination of the foundations of Kashmiri history and society. Situated within the academic field of Kashmiri historiography, this volume challenges the conventional narrative about the region’s ancient past.

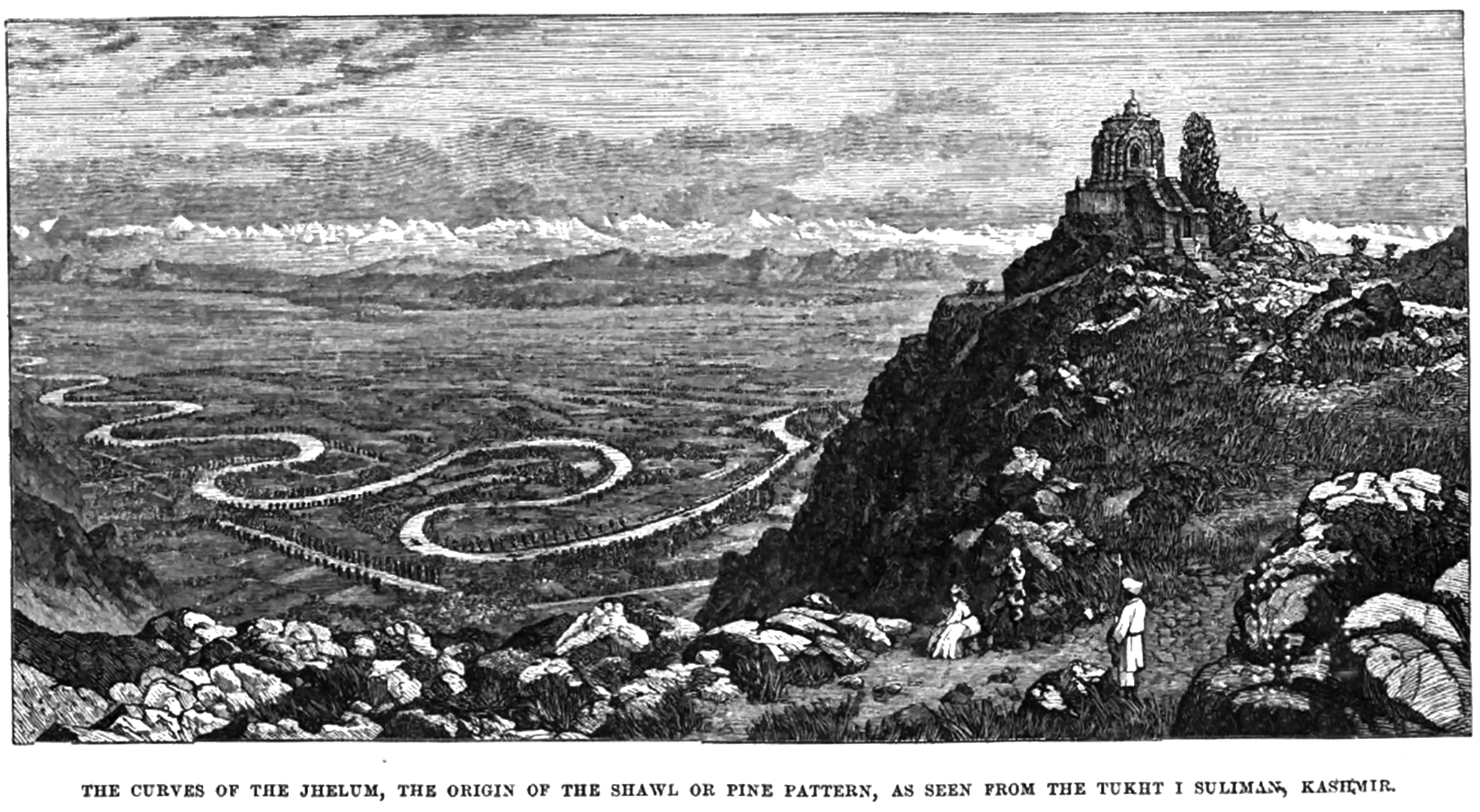

This standard account relies heavily on the authoritative sources of Kashmir’s early rulers and culture. The author contends that Sanskrit texts like Kalhana’s twelfth-century Rajatarangini obscure a critical analysis of Kashmir’s actual origins. As an alternative, he advocates looking for evidence from linguistics, archaeology, material artefacts, folklore, and other vernacular sources. His central argument is that the roots of Kashmiri civilisation lie in the syncretism between early Dravidian inhabitants and later Indo-Aryan migrants, rather than the latter alone as suggested by Sanskritic texts.

Situated as a Kashmiri scholar writing for a local audience, Mohiuddin’s approach is significant in contesting older Orientalist perspectives on Kashmiri history. Colonial scholars like Aurel Stein relied heavily on Rajatarangini, neglecting indigenous sources and oral traditions. The author’s methodology of drawing on multiple disciplines to construct an alternative history aligns with contemporary postcolonial efforts to challenge Eurocentric narratives and re-centre subaltern voices. His fresh approach illuminates the pluralistic cultural foundations of Kashmir and calls for decolonising the understanding of its past.

The Central Question

The central thesis that anchors Mohiuddin’s reinterpretation is that the conventional telling of Kashmir’s history, based almost wholly on Rajatarangini, distorts and conceals the region’s authentic cultural roots. While Kashmir is usually seen as a bastion of Indo-Aryan civilisation, the author argues for recognising its early Dravidian lineage and the synthesis that occurred with Aryan influence. His overarching research question asks: what was the original identity and culture of the Kashmiri people before the dominance of Sanskrit literature and Brahminical ideology starting in the fifth century CE? Related sub-questions explore the nature of ancient Dravidian society in Kashmir, its syncretism with Indo-Aryan migrants, and the process by which indigenous history was overwritten and appropriated by Sanskritic texts.

To interrogate these questions, the author first critically reviews the existing literature on Kashmir’s history, ranging from ancient writings like the Rajatarangini to accounts by later figures like Jonaraja. He highlights the need to look beyond these limited Sanskritic sources that served elite interests and search for alternative perspectives. His thesis builds on modern linguists who have classified Kashmiri as belonging to the Dardic family while situating it concerning current postcolonial scholarship on deconstructing colonial historiography. The book’s implied audience is both Western academics studying Kashmir and local scholars seeking to uncover their own history on its own terms. Mohiuddin’s approach aligns with contemporary movements to decolonise knowledge and rediscover subjugated voices.

Decoding Cultural Memory

To construct an alternative history centred on Kashmir’s indigenous roots, Mohiuddin employs an interdisciplinary methodology that creatively combines tools from linguistics, archaeology, material culture, oral traditions, and textual analysis.

Linguistic Analysis: Mohiuddin examines the Kashmiri language itself for clues to its historical origins. He focuses on phonetic features, grammatical forms, and vocabulary shared with Dravidian languages to argue for its pre-Indo-Aryan substrate. Connections to Dardic languages like Shina are also explored to trace migrations.

Archaeology and Material Culture: The author looks to excavated artefacts, like Neolithic tools and terracotta figurines unearthed at sites like Burzahom, as material evidence complementing linguistic data. These provide tangible proof of the contours of Kashmir’s early indigenous culture before written records.

Folklore: Recognising the limits of texto-centrism, the author analyses Kashmiri folktales, myths, idioms, and oral traditions as sources of popular beliefs and history from below. The cultural memories preserved in these vernacular mediums reveal the persistence of ancient Dravidian concepts.

Textual Analysis: While critiquing the Rajatarangini, the author also engages in textual analysis of terms, idioms, and references to folk customs within Sanskrit works to identify traces of non-Indo-Aryan linguistic and cultural influences. This helps delineate the syncretic process.

Inscriptions: The author provides firsthand epigraphic evidence, like his discovery of a stone slab dated to Jayasimha’s reign near the purported site of Amrtabhavana. The inscription contradicts accepted identifications based solely on interpreting Rajatarangini geographies.

This multidisciplinary methodology combining tools from the humanities and social sciences aligns with current trends in postcolonial historiography seeking to construct subaltern narratives. The author’s excavation of plural sources sounds novel for Kashmiri scholarship when this book was published in 1998 and seminal in decentring Sanskrit texts as the prime authority.

Challenging Popular Narratives

The author thoroughly reviews and critically engages with almost the entire scholarly corpus on the history of Kashmir, starting with the foundational Sanskrit texts themselves. Rajatarangini by twelfth-century poet Kalhana considered the foremost source receives particular scrutiny. The author highlights the need to contextualise its narrative as a literary work rather than an objective history. He argues for analysing it like any other representation shaped by the social milieu and authorial ideology of its Brahmin composer. Later kavya-style renditions of the kings of Kashmir by Jonaraja and Srivara are also assessed as advancing a politicised perspective.

The book provides an insightful review of scholarship by early Orientalists like Sir Aurel Stein, who heavily depended on Rajatarangini for their historical frameworks. The author implicates them in uncritically perpetuating the elite Brahminical narrative and neglecting other evidence that did not fit this paradigm. Their colonial gaze valorised the text as an authoritative relic of ancient Hindu civilisation. The author highlights the need to look beyond such limited sources in reconstructing Kashmir’s past.

In terms of modern scholarship, the author acknowledges his debt to linguists like Grierson who established Kashmiri’s connections to the Dardic language family. He situates his own work concerning recent cultural studies of Kashmiri folklore and oral traditions that provide clues to subaltern beliefs. His interdisciplinary approach aligns with contemporary postcolonial scholarship advocating pluralism in sources and perspectives. The review effectively establishes the book’s niche in contesting Orientalist literature and re-centring indigenous historiography.

Archaeological Alchemy

The archaeological material data encompasses archaeological finds from Neolithic sites like Burzahom dating back to 3000 BCE, including tools, pottery, and evidence of a settled agrarian lifestyle preceding the Indo-Aryan influx. Terracotta figurines depicting folk deities and Tantric practices offer glimpses into early religious stratum. The author provides firsthand accounts of his fieldwork unearthing artefacts like a stone slab from Jayasimha’s reign found close to the site of the purported Amrtabhavana monastery.

The linguistic evidence includes phonological and grammatical structures of the Kashmiri language shared with Dravidian and Dardic vernaculars, and vocabulary from everyday speech and idioms that suggest ancient cultural meanings.

References to Kashmiri folk traditions in Sanskrit texts are analysed. Inscriptions dating artefacts and place names in old Kashmiri terminology provide epigraphic confirmation. Folktales about mythical characters, fairies, and animal fables that encode community beliefs are also scrutinised.

This aggregation of material, linguistic, textual, and oral data from diverse sources lends credibility to the author’s revised narrative. He succeeds in looking beyond just Rajatarangini to incorporate a wealth of alternative evidence foregrounding Kashmir’s indigenous heritage and identity. The methodology can serve as a model for decolonising the historiography of other regions as well.

Mythic Geography

The author’s core thesis comprises two strands of argumentation: first, convincingly dismantling the mainstream narrative about Kashmir’s ancient history centred solely on Sanskritic texts and the Indo-Aryan civilisational sphere; and second, his positive reconstruction of an alternate account highlighting the Dravidian substratum and hybridity with later cultures. His analytical strategy combines critical deconstruction with the synthesis of multidisciplinary sources towards reclaiming Kashmir’s ethno-linguistic heritage.

On the deconstructive side, the author interrogates the Orientalist and nationalist paradigms that privileged texts like Rajatarangini. By exposing contradictions within Rajatarangini’s mythic geography and questioning colonial historians’ faulty identifications of place names, he destabilises the text’s authority. His analysis reveals the political motivations underlying the valorisation of particular narratives that erase indigenous voices.

The synthetic aspect comes through in his insightful integration of evidence from archaeology, language, iconography, oral traditions, and inscriptions to reconstruct Kashmir’s cultural matrix before and alongside Sanskritic influence. Close readings of shared linguistic features and relics of material culture convincingly demonstrate the region’s pre-Indo-Aryan Dravidian provenance that deeply shaped its language and society. The author weaves together these disparate threads into a compelling counter-narrative affirming Kashmir’s pluralism.

His argumentation could be strengthened with more theoretical framing. Elucidating his conceptual approach more explicitly in terms of post-colonialism and subaltern studies would help situate the work within contemporary academic discourse on decolonising history and challenging hegemonic narratives from the periphery.

Cultural Hybridity

While the author does not elaborate on an overarching theoretical framework, his approach embodies several relevant concepts. Firstly, his sceptical reading of colonial historiography and emphasis on excavating indigenous epistemology mirrors trends in postcolonial theory that challenge Eurocentric knowledge. The Foucauldian principle of interconnected power and knowledge undergirds his critique of how hegemonic Sanskrit narratives shaped Kashmiri historiography. His methodology of trawling alternative vernacular sources accords with Subaltern Studies’ efforts to uncover repressed voices excluded from elite accounts.

Secondly, the author’s highlighting of syncretism between the early Dravidian society and Indo-Aryan incomers draws implicitly on theories of cultural hybridity and creolization (the process of mixing two or more languages to create a native language). His excavation of shared linguistic and artistic forms resonates with Homi Bhabha’s concept of the Third Space of cultural mixing. The author’s account parallels the model of creolization demonstrating linguistic and cultural syncretism between indigenous and invading groups. Integrating these frameworks enriches the author’s theoretical basis.

Lastly, his retrieval of indigenous folk knowledge aligns with trends in de-colonial theory that challenge the erasure of subjugated epistemologies. His methodology centring on material culture, vernacular artefacts, and oral traditions as sources accords with decolonial efforts to look beyond archives and texts towards plural cosmologies and ways of knowing. Situating his approach within these critical theoretical paradigms would help strengthen the book’s postcolonial intervention.

Marginalized Histories

The book intervenes in nationalist portrayals of Kashmir as a timeless Hindu cultural bastion. By highlighting its plural roots, the author contests the appropriation of Kashmir’s past to legitimise ideological claims.

The work represents an early and comprehensive endeavour to construct a Kashmir-centric historical narrative based on indigenous sources, a departure from Western Orientalist interpretations. The author diligently recovers forgotten Kashmiri voices and epistemologies, steering away from conventional narratives. Employing a pioneering multidisciplinary framework that integrates tools from linguistics, archaeology, anthropology, and literary analysis, the author innovatively approaches historical inquiry. This interdisciplinary method for excavating the subaltern past stands out as a significant contribution.

Besides, the author challenges the oversimplified dichotomy between Sanskritic and Indo-Aryan cultures versus indigenous Dravidian society in Kashmir, offering a nuanced account of their syncretism and hybridity that defies Orientalist simplifications.

The author’s articulation of an epistemology rooted in local Kashmiri knowledge systems serves as a model for reclaiming marginalised histories. This methodology aligns seamlessly with the broader objective of decolonising historiography, illustrating a thoughtful and progressive approach to the study of the region’s rich and complex past.

Through these contributions, the author significantly expands the conceptual horizons for researching Kashmir’s history and culture. His book lays the foundations for decolonised and critical historiography grounded in vernacular epistemology.

Theoretical Grounding

While the book provides a compelling alternate framework, a few aspects could have benefited from more elaboration. Firstly, the revisionist narrative could have been strengthened by greater engagement with indigenous Kashmiri histories like the now-lost text Patanjali Muni Vamshavali mentioned as Kalhana’s predecessor. Though he acknowledges the loss of many native chronicles, directly addressing what is known of such works would reinforce his critique of the erasure of local histories.

Secondly, the linguistic analysis of Kashmiri could unpack in more technical depth the specific phonetic, morphological, and lexical features shared with Dravidian languages like Tamil or Telegu. Providing more expansive evidence of the hypothesised linguistic commonalities might have bolstered this aspect of his argumentation. Engaging critically with recent historical linguistics scholarship on language contact and convergence could also add richer theoretical grounding.

Lastly, while the book productively contests Orientalist historiography, it would benefit from more directly situating itself within the lineage of postcolonial or subaltern theorisations of history and identity. Explicitly linking the author’s approach with seminal works by figures like Ranajit Guha, Dipesh Chakrabarty, Gyan Prakash and others would accentuate the book’s contributions to decolonizing knowledge.

These limitations notwithstanding, the author accomplishes the groundbreaking task of excavating Kashmir’s plural legacy using innovative multidisciplinary tools. He lays a seminal foundation for other scholars to build upon through further linguistic study and theoretical contextualisation. The book’s call to decentre elite discourses remains valuable.

A Gateway to Syncretic Complexity

The author’s revisionist account is suited for both academic and non-specialist audiences interested in Kashmir’s distinctive culture and contested history. The interdisciplinary approach combining literary, linguistic, anthropological, and archaeological sources makes it valuable for researchers in those allied fields. South Asianists, historiographers, students of ancient languages, and postcolonial scholars would particularly appreciate its methodological contributions and theoretical implications.

Besides the Western academe, the book crucially seeks to decolonise perspectives among Kashmiri society itself. By contesting the homogenising tropes of Hindu nationalists that appropriate Kashmiri culture as singularly Sanskritic, the author pens a narrative that ethnic Kashmiris could recognise as their own. His excavation of plural indigenous foundations would resonate with civilians interested in their hidden heritage. However, prior background knowledge of South Asian history, languages, and key texts enriches engagement with the book’s specialised arguments.