Chitralekha Zutshi’s book, Sheikh Abdullah – The Caged Lion of Kashmir is by far the most perceptive work on Abdullah but is short of being the definitive text, writes Haseeb A Drabu

Chitralekha Zutshi’s direct and rather devastating conclusion that “in the end, Abdullah’s life illustrates that it was impossible to be both a patriotic Kashmiri Muslim and a loyal Indian at once” should set the cat among the pigeons. This is an existential issue even today. More so now, not just for the political leadership but also for the people of Kashmir. While unlikely to trigger an introspection on either side, the book could not have come at a more appropriate time. If not a happy coincidence, it has to be a clever marketing plan of the publishers to release it around the time of the Supreme Court verdict on rescinding the special position of Jammu and Kashmir.

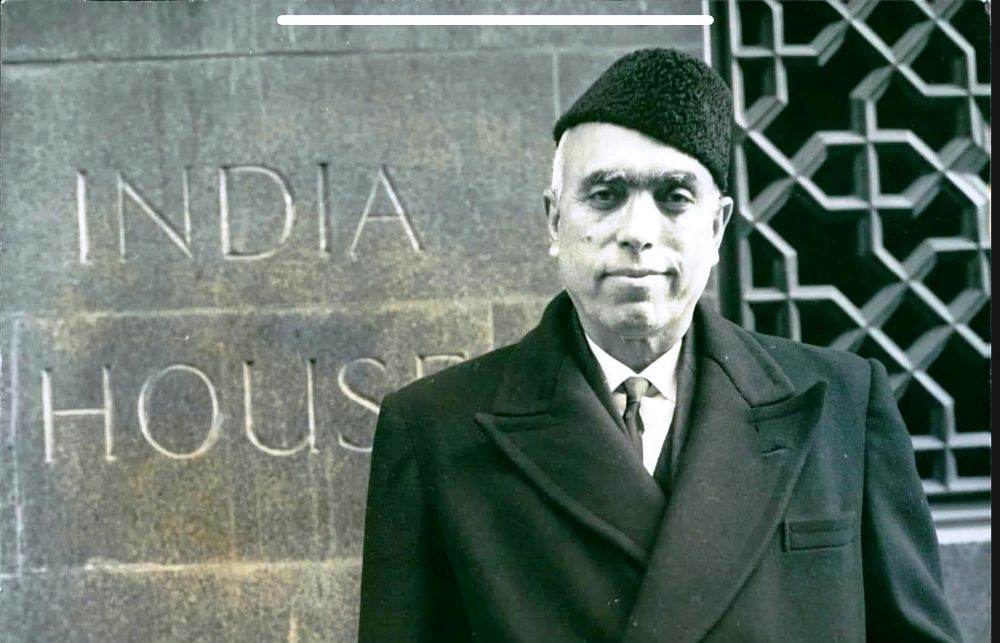

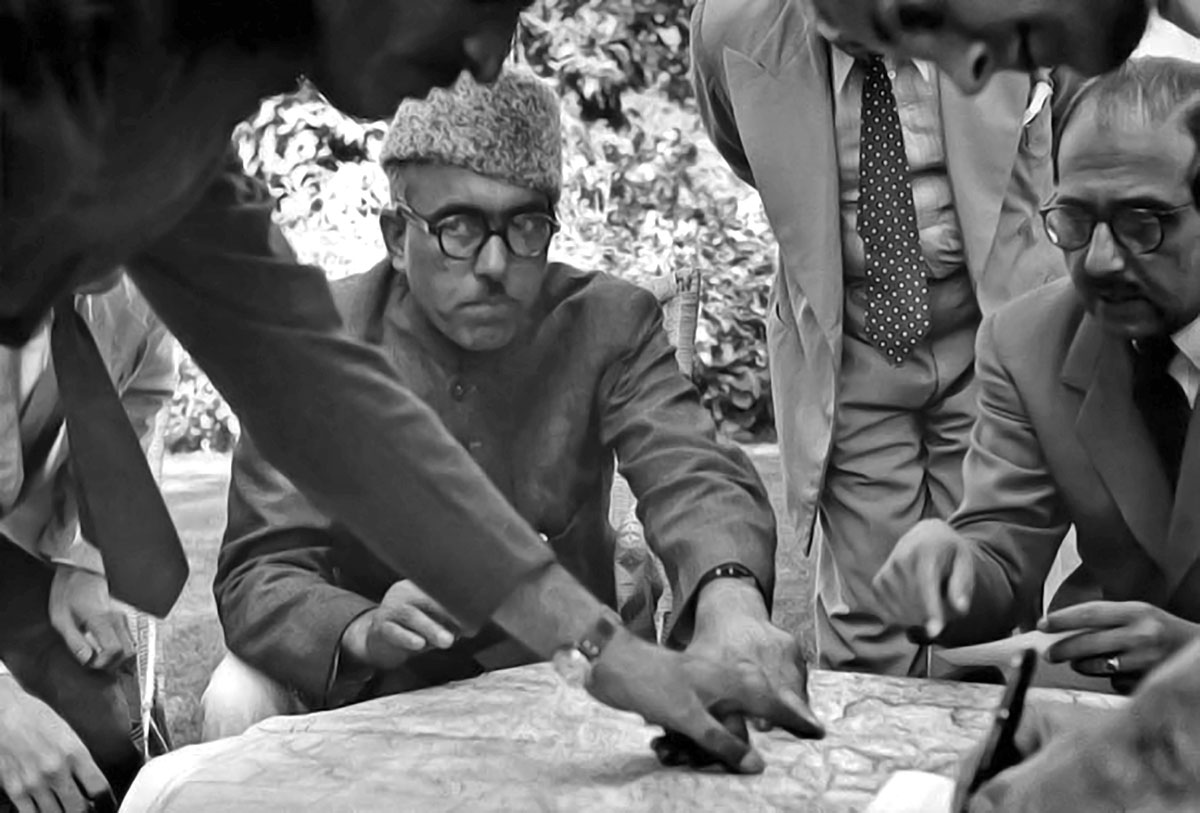

The protagonist of the book, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, personified the body and embodied the soul of that special position. In Zutshi’s words, “It was Abdullah who built his entire career around Kashmir’s special status within India, promoting himself as the protector”. He is credited (or as some would argue, discredited) with having driven the plot of Jammu and Kashmir’s accession to India on specific terms which, though diluted over the years, became the rules of engagement from 1951 till 2019.

While Sheikh Abdullah, who self-confessedly lived all his life with the uncertainty of “India unilaterally changing the relationship and coercing the state into a more subservient position in the future”, died in 1981, his political legacy was buried by the Indian State in 2019 and an uncharitable epitaph was written by the highest institution of civil society, 2023.

This book is also timely for the generation which is growing up at a time when the government is in the process of airbrushing Abdullah from public memory. His birth anniversary is no longer an official holiday. The police gallantry medals are no longer inscribed with his commemorative epithet. The iconic SKICC has dropped the prefix to become Kashmir International Convention Complex. And so on.

Scholarly Work

The author, who has a significant and serious body of scholarly work on Kashmir to her credit, provides by far the most cogent and consistent account of Sheikh Abdullah and a wide perspective of the centre stage of politics and the political matrix that he occupied. The book is written pleasantly avoiding the arcane academic style, making it very accessible. This narrative has an underlying empathetic tone which juxtaposes well with her academic objectivity in dealing with facts. This lies at the heart of why the book is balanced, a rarity in the Kashmir context.

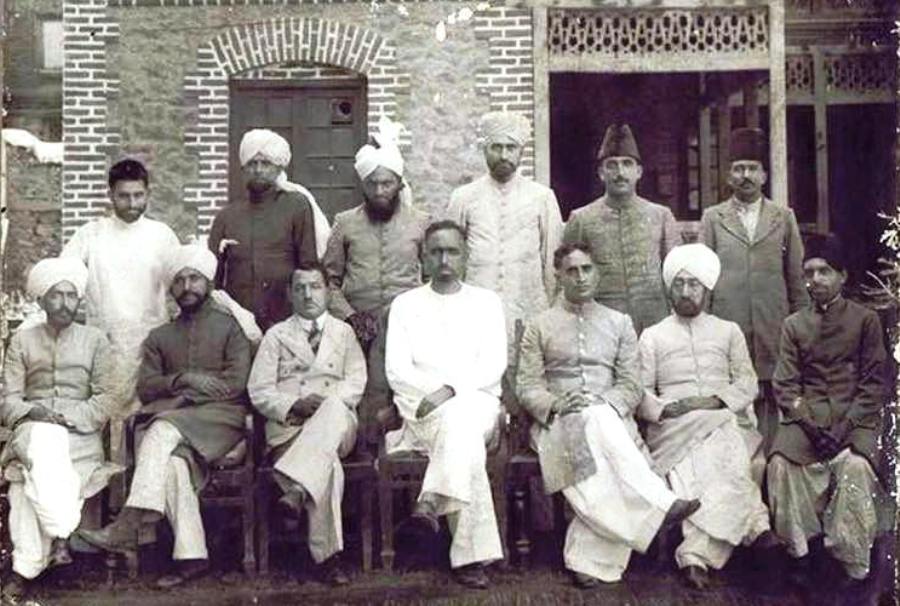

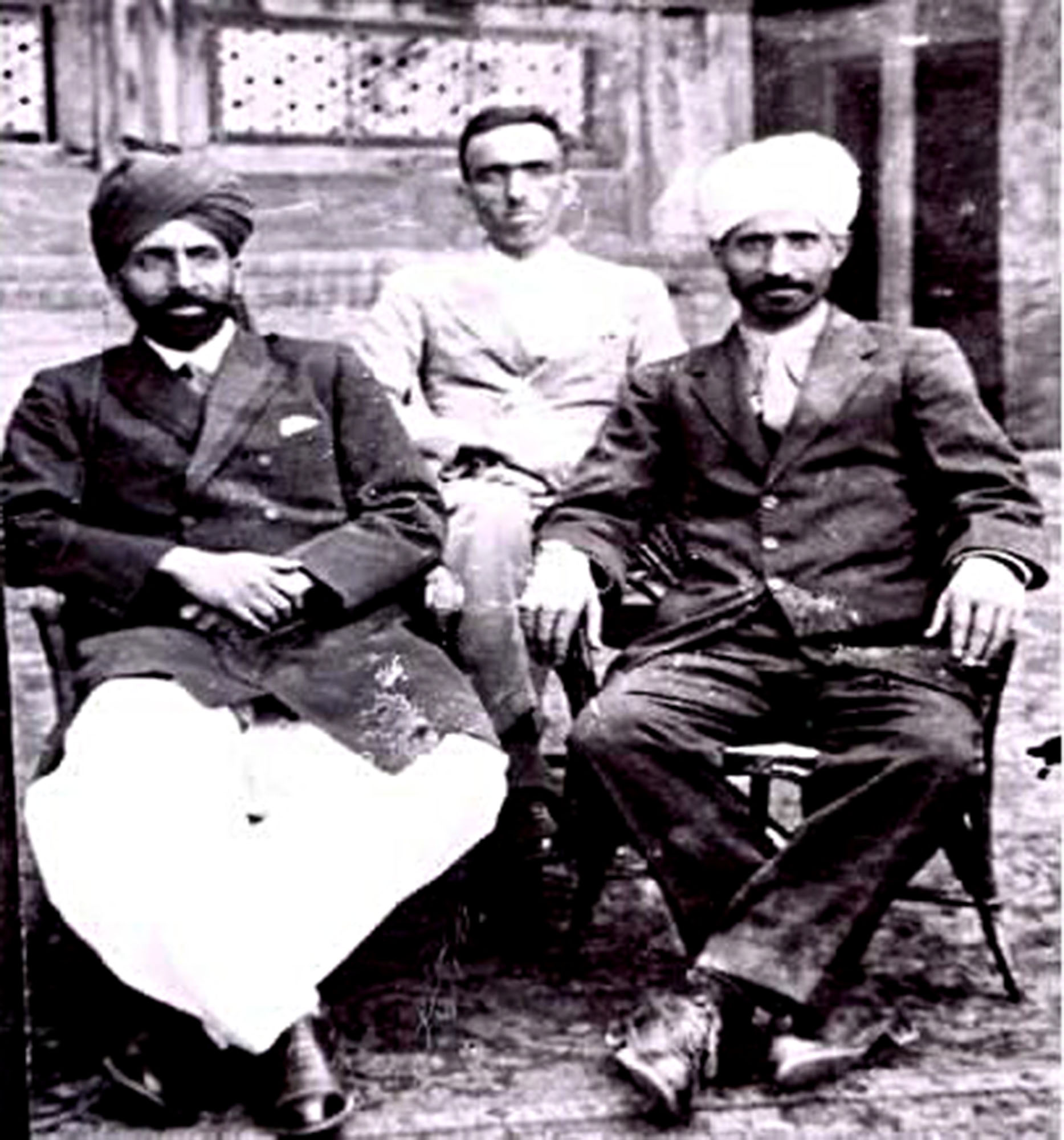

Zutshi’s overall approach to unravelling the “complex and controversial” Abdullah is seasoned though not quite as refreshing. She brings to life the anti-feudal resistance fighter of the early thirties, the pragmatic secularist of the late thirties, the emotional communist of the mid-forties, the egalitarian head of government in the late forties, the ethnic nationalist of early fifties, and desperate politician of the mid-seventies.

Quite expected, she moves away from the hagiographical narrative of most of the earlier biographical works on Abdullah. The main contribution of the book lies in placing Sheikh Abdullah, the tallest leader of Kashmiris, in a larger context of postcolonial politics. This has led her to describe Abdullah as a “thoroughly South Asian political life in the global twentieth century, which while singular in many ways, was by no means unique in its vision, contradictions and comprises”.

The well-established patterns, paradoxes, and policies of post-colonial politics across continents and countries find many parallels in the politics in Kashmir. This makes the book a stimulating read, especially the depth and detail in which the author has connected the micro-events with macro political situation. It turns out that Abdullah was a “participant and a victim of the post-colonial state’s agenda of integrating and centralising its diverse territories”.

Identity, Autonomy

Zutshi has tried to show how the anxieties of post-colonial India – nation, territory, and sovereignty – were not just different but antagonistic and opposed to the aspirations of post-feudal Kashmir be it ethnicity, identity, and autonomy. Having been the only place where ideology and conviction overruled religion as the consideration for accession, the focus and sensitivity on these were far greater.

In a multipolar world, with India an acknowledged soft power, aspiring to be a superpower, it may be hard to imagine today the geo-strategic importance of Kashmir during that time. It is no coincidence, for instance, that the first Constitutional Order issued by the President of India severely curtailing the autonomous position of Jammu and Kashmir came within days in 1954, days after Pakistan signed a military pack with the US and entered SEATO. It was such a complex confluence of local, domestic, regional, and international factors that were at play and not so much his whimsical nature and behavioural inconsistency in the political arena. True, most politicians, observers, and bureaucrats do concur with his ideological ambivalence and political unreliability.

Turbulent Relationship

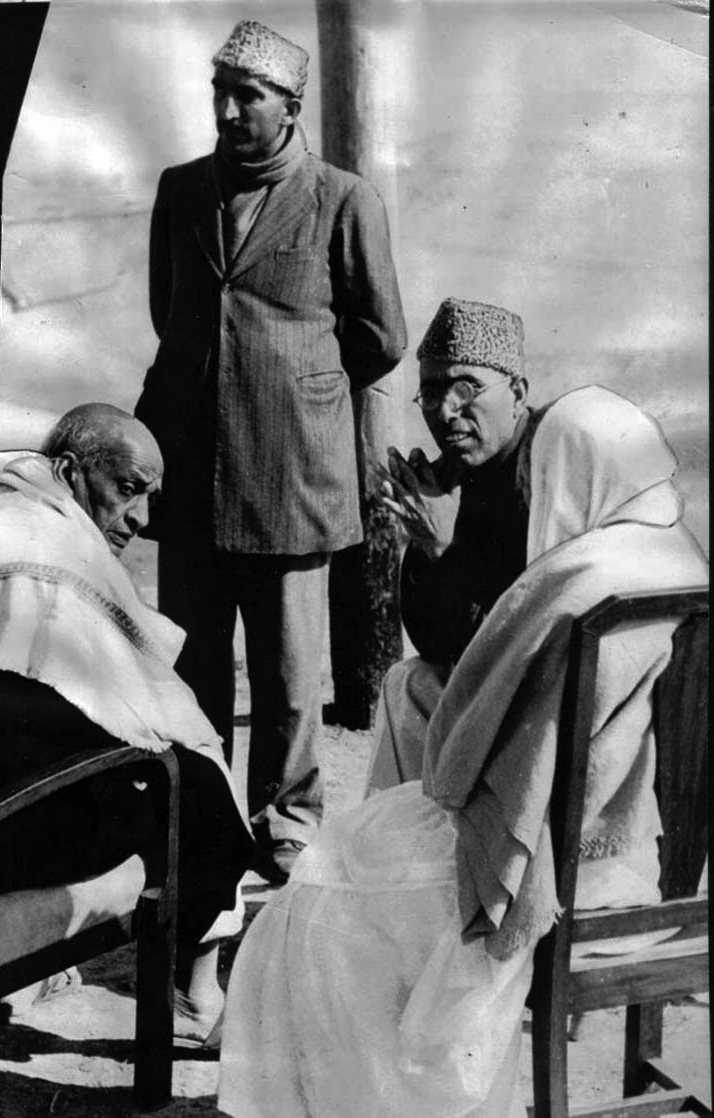

While accounting for the “turbulent relationship”, Zutshi doesn’t attribute Abdullah’s widely varying and often inconsistent political positions to his interpersonal relations with Nehru. Apart from an extensive and rather self-indulgent biography, hagiographies are masquerading as the history of Jammu and Kashmir. In these, the dominant narrative is so overwhelmed by this interpersonal relationship that the history of Kashmir and its governance is akin to an unending soap opera of Nehrus-Abdullahs. Season two being Abdullah-Indira, with season III being Farooq-Rajiv and season IV Omar-Rahul!

Likewise, it was not his gravitas and stature that catapulted Sheikh Abdullah to the international arena rubbing shoulders with heads of nation-states like Khrushchev, Chou en Lai, and others. It was the nature of the dispute that he was representing. More often than not this subtle but distinction gets lost on the masses and even Abdullahs themselves.

Judgmental Qualification

The sub-title of the book seems to emphasise the same point by qualifying his title of Sher-i-Kashmir with the prefix “Caged”; a loaded and judgmental qualification. It is not to be mistaken as a metaphor for “the 16 years 6 months and 22 days of Abdulla’s incarceration”. The cage is the creation of the various regional, domestic, and international factors that were at play.

While the cage may not have been of his own making, the question lingering in my mind after reading the book: was he more tamed than caged? While being in complete agreement with the author on the approach and analysis, there is more to Abdullah’s political choices than the sheer force of circumstances.

It can be argued his political conduct and choices were to a large extent driven by the conflict between his stated ends and deployed means. For instance, while his ends may have been secular, his means were consistently and unambiguously religious. And at many times his mutually conflicting ends. No one has summarised it better than Josef Korbel in his book, Danger in Kashmir, as early as 1954, saying Abdullah was a “Communist in Jammu, Communalist in Kashmir and Nationalist in Delhi”.

Definitive Biography?

While this is an outstanding book, it stops short of being the definitive biography of Sheikh Abdullah. It enhances our understanding by contextualising well-known events and incidents and connecting the dots. The political storyline, which at times appears overly balanced, is self-consistent but doesn’t answer all the questions. Perhaps, some more research on certain aspects which have not been adequately emphasised would make it more comprehensive.

A case in point is the impact of the failure of the Cabinet Mission Plan on Jammu and Kashmir. His biggest failure was in not seeing how his model could not fit the changed scheme. Right up until June 3, 1947, Sheikh Abdullah couldn’t have been faulted for believing in creating an autonomous unit. Till then the federal system envisaged – proposed by Jawaharlal Nehru in his “Objectives Resolution” and approved by the Constituent Assembly on December 13, 1946 – had minimal powers to the Centre leaving maximum autonomy, including residuary powers, to the constituent units.

In this scheme, the states were to possess and retain the status of autonomous units, together with residuary powers, and exercise all powers and functions of government and administration, save and except three such powers and functions – Defence, Foreign Affairs and Communication — vested in or assigned to the Union. It fitted perfectly with the Kashmir model. In fact, it was the Kashmir model before Kashmir!

This approach was abandoned, and the resolutions were recast given the political changes resulting from the partition. The British Plan leading to the partition of the country had an immediate and profound impact on the Constituent Assembly and its Union Constitution Committee and Union Powers Committee headed by Nehru. Post partition plan, there was a great deal of support in favour of a strong Centre with residuary powers. In this framework, creating an enclave of federalism within a union of states was not going to be just an incongruity but also an anomaly.

The Sacred Spaces

At another level, for instance, Zutshi has written about Sheikh Abdullah’s use of “scared spaces” but it hasn’t been dealt with adequately. How Sheikh Abdullah used religion for political purposes needs more intensive research.

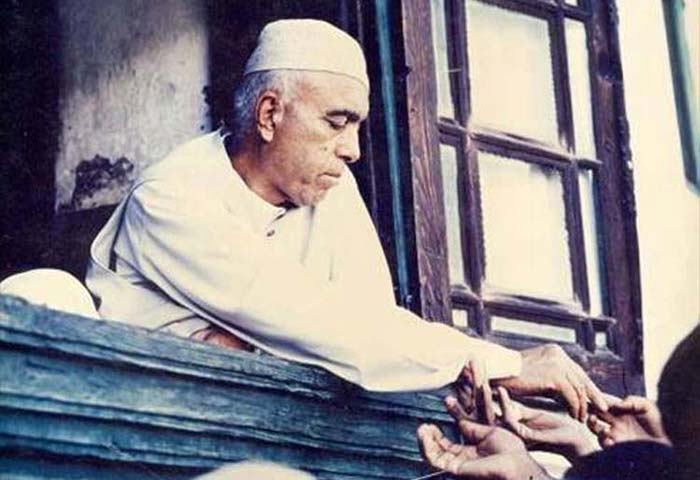

No politician in India, let alone Jammu and Kashmir, has used religion for political purposes more and more effectively than Abdullah. The use of religion and the local belief system was a core component of his political strategy. He used religion as a forum for strengthening his political legitimacy, religious institution as a party platform giving divine sanctity to his initiatives and programmes and religious practices for making the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference’s political agenda almost a religious obligation. No one has converted the pulpit of the mosque into the podium of politics like Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah did, that too without being a cleric! It is a masterclass in leveraging religion for political purposes.

Far from analysing this, Zutshi shows a rate instrumentalist streak by arguing that “the most important function served by the (Auqaf) Trust was to assure Kashmiri Muslims on the ground that Abdullah remained their spiritual leader”. The Auqaf was created as in institution of the Muslim civil society, a vehicle of control over the social capital of the Kashmiri society as also a trespassing into the Mirwaiz religious territory.

Quite apart from that, Zutshi goes overboard by mentioning more than once about Sheikh Abdullah “confirm(ing) his status for Kashmiris as a great spiritual leader”. He was never seen as a spiritual leader at any stage of his political career. He was, of course, seen as a devout Muslim who had the blessings of the divine. There are very definitive views on Sheikh Abdullah’s connect with the spiritual. The highly respected and regarded dervish, Kausar Ali Shah, an Afghan, popularly known as Kausar sahib, is once known to have advised Begum Abdullah, to separate from him if she was seeking salvation.

Muslim Segmentation

Indeed, how he conducted his political communications, resulted in a segmentation of the Kashmir Muslim population which resulted in the politicisation of the 200-year-old Mirwaiz tradition. Mirwaiz Yusuf Shah, a Deobandi alumnus, to eliminate the threat posed to his position by Sheikh Abdullah, set up his political party, the Azad Conference in 1933. This was the first time, a Mirwaiz had got involved with political activism and party politics. This had implications not only for the politics of Kashmir but also the society. Zutshi hasn’t explored in any depth or detail the relationship between Sheikh Abdullah and Mirwaiz besides the usual. To the extent that cultural identity was built by othering the Mirwaiz, this is a gap.

Similarly, while much has been written and documented about Abdullah’s relationship with the Indian state and state actors, not much is talked about his relationships with the larger Indian civil society other than communists including some big names like Faiz Ahmad Faiz whose marriage he solemnised. What was his understanding of, and with, the Muslim civil society, its religious leadership and the social elite? How did they see his politics which had a huge bearing on their existence? Was there any understanding or effort to influence his decisions? It used to be an oft-repeated phrase during that period that the Kashmiri Muslims were being hostage for the Indian Muslims. The two have no history of being socially or culturally connected.

Interestingly, it was the briefing by G A Ashai on the plight of Indian Muslims in India that triggered a rethink in Abdullah in 1952. Ashai, a mentor of young Abdullah, who had been appointed Registrar of the University, went on an extensive tour of the country under the pretext of studying the Indian University system. He got a sense of the civil society in India vis a vis Muslims and came back a deeply disappointed man. He warned Abdullah, a point that Zutshi mentions.

Party Shift

Another very significant aspect, that of political demography, which determined his political equations did not get the due attention from Zutshi. The change of name from Muslim Conference to National Conference or the flirtations with the Ahmadiyya, for instance, was nothing but a manifestation of the deep-seated fear of political demography that was stacked against him. Going by the Census of 1941, the Kashmiri-speaking Kashmiris at that time were in a minority. The Punjabi-speaking Kashmiris were in the majority. Is it a sheer coincidence, that the Line of Control (LoC) actually overlaps the linguistic border? Sheikh Abdullah played a decisive role in drawing the LoC, sitting as he was in Delhi when the Indian Army was pushing back the raiders.

It has been well established by Defence experts in their domain journals, (an oft-ignored rich source material on Kashmir) that the Indian Army could have pushed the raiders beyond Uri but curiously didn’t. If this aspect is studied in detail, it will yield a rich narrative on many critical aspects of not just the politics but also the geography and the constructed Kashmiri identity.

In fact, a fascinating part is the definitional malleability of the Kashmiri identity; it constantly gets redefined in relation to the political exigency and adversary. So when Mirwaiz was the political adversary, Kashmiriyat was about syncretism and Sufism, but when Chaudhry Abbas was the opponent, linguistic identity got the primacy in defining Kashmiriyat.

Within the multi-layered ethnic and linguistic plot of Jammu and Kashmir, Zutshi in treating Jammu as a monolithic province, is losing sight of an important sub-plot in the politics of Kashmir. Other than the Tawi basin, the political geography of the other two regions; Pir Panchal and Chenab are an extension of the Jhelum Valley. The point is that the politics of Pir Panchal and Chenab would reflect their social, cultural, linguistic, and geographical relationships with the valley. And by default the politics.

An Endearing Read

Notwithstanding these minor quibbles, what will make this book an endearing read for a lot of Kashmiris is the skilful use of sotto voce, political folklore, and personal anecdotes to give the narrative a distinctly local flavour and sensibility. Her use of oral histories in its nuances and intonations have been woven anecdotally to depict the mood, buttress or discount a political observation.

For instance, how the screening of the film Omar Mukhtar triggered anti-Abdullah demonstrations, part of the political folklore generations have grown up with in Kashmir, makes the historical narrative textured and real. Besides, providing a new interpretive perspective on the underlying politics. Or the iconic cartoons of Kashmir’s very own R K Laxman, BAB, documenting and commenting on Abdullah’s personality and politics. Even as all this humanises Abdullah, it adds to his stature more than it takes away from it. She brings out his vulnerabilities and insecurities as much as his strengths. In that sense, it is a well-balanced biography from an empathetic perspective.

The archival research is outstanding. She has dug up the most obscure of references to buttress her contentions. Some of these references are not only new but valuable. The bibliography and referencing are extensive. I just wish that the publishers had gone with a footnote structure rather than an endnote format. Going back and forth in such an extensively referenced work is quite a painful distraction.

(An economist, the author was the finance minister of Jammu and Kashmir state.)