When a French farmer’s physician son, François Bernier accompanied the Mughal Emperor to Srinagar in 1658 summer, he left a detailed account of Kashmir’s life, livelihoods and culture for history, writes Muhammad Nadeem

François Bernier’s life was defined by a restless curiosity that led him on an extraordinary intellectual and physical journey across cultures, countries, and continents. Born to humble farming folk in rural France in 1620, nothing foreordained the global odyssey that would unfurl over the next seven decades of Bernier’s life. Propelled by an inquisitive disposition, Bernier stepped onto the world stage as a young man hungering for knowledge and experience.

Initially, he travelled across northern Europe where he immersed himself in the cultural milieus of Germany, Poland, Switzerland and Italy. This awakened in him an appreciation for diversity and planted the first seeds of a lifelong passion for understanding foreign societies. Bernier’s wanderlust was soon channelled into more structured pathways when he enrolled at the medical school at the University of Montpellier in 1652. There, Bernier was mentored by philosopher Pierre Gassendi who nurtured his analytical faculties and empirical bent of mind.

Armed with the scholarly training to observe and document the world around him, Bernier next voyaged to the Levant region, soaking in the heady cultural syncretism of Palestine and Syria. However, the East continued beckoning Bernier irresistibly. An intrepid risk-taker, he next voyaged down the Nile into Egypt and lived in Cairo for over a year. Braving disease, unrest and uncertainty, Bernier was driven by an almost spiritual quest to expand his horizons and understand humanity in its dizzying diversity.

The fates soon conspired to set Bernier on a journey that would define the rest of his life – his passage across the Indian Ocean in 1659 to Hindustan, the world of the Mughals. Arriving at the heights of the Mughal Empire, Bernier had won for himself a front-row view of history. He witnessed the pivotal Battle of Deorai that marked the decisive victory of Aurangzeb in the Mughal War of Succession. In Aurangzeb’s India, Bernier was more than a scribe of events alone – he was smack in the middle of them.

Bernier’s writings reflect his access to the beating heart of the Mughal Empire. His frank impressions and shrewd observations shed light on the central personae that peopled the halls of power in 17th-century India. From the devoted Dara Shukoh who bought Bernier his first elephant to the coldly calculating Aurangzeb whose company Bernier kept for months, his accounts provide candid portraits of the emperors and princes who shaped the fate of the subcontinent.

Bernier’s writings also present a vivid travelogue capturing the sheer wonder he felt at the marvels of the verdant vales of Kashmir, the pulsating bazaars of Agra, the imperial spectacle of Delhi’s parades, and the wild majesty of a hunt with trained cheetahs. He describes himself as the wide-eyed foreign wanderer, permitted by happy accident to infiltrate exotic worlds beyond his wildest dreams.

Through all his rich experiences, Bernier also evolved into an incisive observer of the Mughal state and society. He commented extensively on land revenue policies, military systems, official hierarchies and the condition of peasants. Beneath the surface glitter, Bernier’s analytical eye discerned systemic rot – signs of the decline that would unravel the mighty Mughal edifice over the coming century.

Having witnessed the most dramatic chapters of 17th-century Indian history unfold before his eyes, Bernier returned to his native France, eager to commit his memories to writing. But India had suffused his soul and after brief interludes in his homeland, Bernier almost inevitably gravitated back towards the East. His next decade was spent traversing the expanses of Persia in circular odysseys before he returned to settle in Paris in 1670.

The final years of Bernier’s life were devoted to publishing his travels and cementing his legacy as one of the foremost chroniclers of Mughal India. Though Bernier is relatively unknown today, his writings were devoured by Europeans of his time, transporting armchair travellers into intoxicating worlds beyond their borders. More than just popular entertainment, Bernier’s accounts shaped European ideas about the Orient. Scholars continue to mine his work for precious first-hand insights into the social, cultural and political life of the Mughal realm.

In Kashmir

In his first-hand account of travels across the Mughal Empire, the French physician François Bernier provides an insightful glimpse into the pomp and circumstance surrounding the Mughal court and its machinations. Through an evocative portrayal of his prolonged sojourn traversing the plains of North India and ascending into the fabled Kashmir, he unravels the spectacle of the Great Mughal procession in all its unhurried and ceremonious glory.

Through his “outsider looking in” lens filtered through European sensibilities, Bernier’s travelogue covers the minute details of mobile Mughal courtly existence in lively, captivating prose. Like a modern ethnographer, Bernier renders the finest granularity of courtly life amidst military processions comprehensible to continental European audiences.

The freedom to access the innermost sanctums of the court and army on a campaign that Bernier enjoyed was unprecedented and astonishing for a European traveller, allowing him to provide what is perhaps the most extensive eyewitness account of mobile Mughal governance. He leverages this privilege to stress the grandeur, wealth and might of Indo-Persian Mughal power at its apogee, memorably brought to life through striking descriptions of Kachemire’s paradise and performative civilizational prowess. This laudatory tone sets him apart from contemporary European commentators who tended to denigrate Eastern Mughals from a position of cultural superiority. For Bernier, there is no doubt that 17th-century Mughal India should be considered a worthy civilizational equal “if not superior to contemporaneous European monarchies”.

Through Bernier’s descriptions, we traverse immense distances, experience extremes of heat and cold, witness the spectacular military encampments of the great Mughal ruler Aurangzeb, and ultimately arrive in the idyllic paradise of Kashmir.

His account transports us back to the scorching Indian summer, as Bernier joins the emperor’s vast entourage departing Delhi in May 1658, at the onset of the hot season: “The heat was insupportable. There is not a cloud to be seen nor a breath of air to be felt…I feel as if I should myself expire before night.” Bernier notes incredulously that despite the extreme conditions, the camp numbers at least 250,000 people and animals – a migrating city transporting the entire nobility and military of the empire, along with all their attendants, families, and possessions.

The Caravan Moves

Bernier’s travelogue offers a vivid sense of the scale and extravagant pomp of the Mughal court, with frequent hunting parties and lavish displays of wealth contrasting with the ascetic lifestyles of their subjects. There are scenes of chaos and calamity, as when crossing swollen rivers on makeshift pontoon bridges: “numbers of camels, oxen, and horses were thrown down, and trodden underfoot, while blows were dealt about without intermission.”

After eleven gruelling days under the baking summer sun, the terrain finally changes as the party approaches the entrance to the mountains of Kashmir near the town of Bhimbhar. Bernier evokes both the sublime beauty and ever-present danger of the high mountains, describing: “a steep, black, and scorched mountain…We are encamped in the dry bed of a considerable torrent, upon pebbles and burning sands, a very furnace.”

The logistics of moving the Mughal camp through the treacherous high mountain passes provides insights into the Mughal military efficiency. The advance sections of the party have gone ahead, while stragglers will follow to avoid congestion on the narrow cliffside tracks. Goods and supplies have been sent ahead for months. Transport switches from camels to legions of human porters – Bernier notes astonishingly that 30,000 local porters have been enlisted, with the emperor personally requiring 6,000.

Bernier’s wonder and curiosity permeate the letter, consciously risking his life to experience the allure of Kashmir first-hand: “What can induce a European to expose himself to such terrible heat, and to these harassing and perilous marches? It is too much curiosity, or rather it is gross folly and inconsiderate rashness.” For Bernier, crossing the Pir Panjal mountains to experience the delights of the Kashmir valley compels him irresistibly forward, using this hazardous journey also as an opportunity to demonstrate his fortitude and powers of observation.

As the terrain changes, so does Bernier’s mood, the cooler climate restoring his vigour as the party finally encamps near Kashmir: “The atmosphere is cooler, my appetite is restored, my strength improved,” He recorded. Like the archetypal hero returning triumphantly home, the epic journey culminates as Bernier approaches the semi-mythical earthly paradise of Kashmir, rendered glorious by the tribulations endured to reach it. Through rich sensory details, epic stories and personal musings, Bernier’s account provides glimpses of the last magnificent days of the Great Mughals.

Through an extensive letter written to a friend after a three-month sojourn there, Bernier brings alive the beauty and abundance of this “terrestrial paradise of the Indies,” explaining its unique geography, climate, flora, and fauna as well as extolling the industry and appearance of its inhabitants.

A Transplanted Europe

After traversing the “frightful wall of the world” that is the steep, imposing mountain pass of Bember, Bernier is struck by the dramatic change in climate as he essentially transitions “from the Indies to Europe.” He breathes cooler, fresher air and is surrounded by fir, oak and plane trees reminiscent of the forests of his native Auvergne rather than the tropical landscape left behind. This evocative personification of Kashmir as Europe transplanted continues as he elaborates on the valley’s mild weather, fertile soil and the plethora of familiar flowers, fruits, and vegetables.

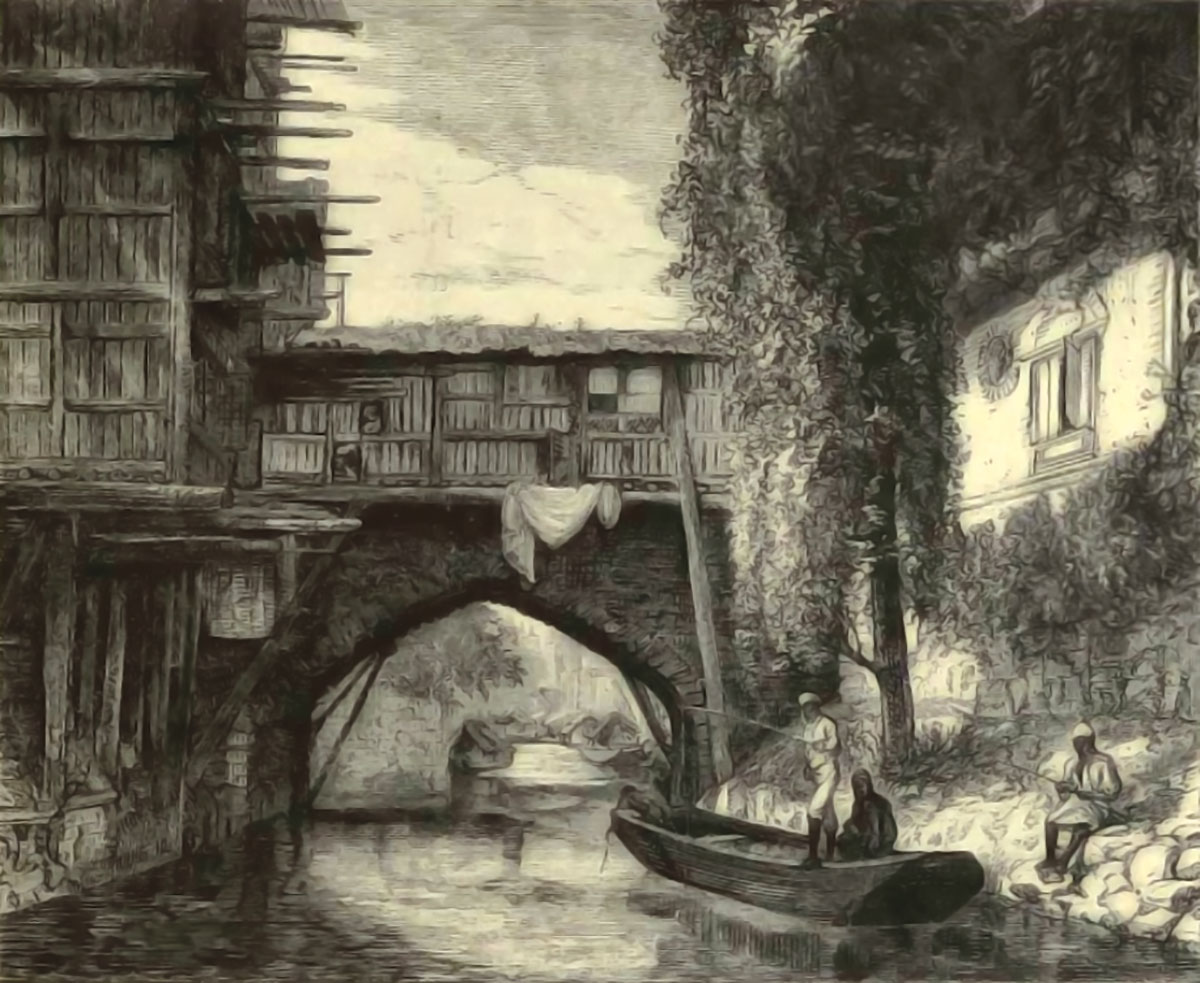

Central to his lavish portrayal is Kashmir’s setting as an alpine valley cradled by the Himalayas, described poetically as “mountains whose summits, at all times covered with snow, soar above the clouds and ordinary mist, and, like Mount Olympus, are constantly bright and serene.” He traces the origins of this valley lake according to legend, postulating more logically that it was formed by a sinking mountain and subterranean erosion rather than manually excavated by a saint. Crucially, it is now channelled by the outlets and canals into a peaceful river that winds through Kashmir’s capital Srinagar, fringed by charming houses with pretty gardens.

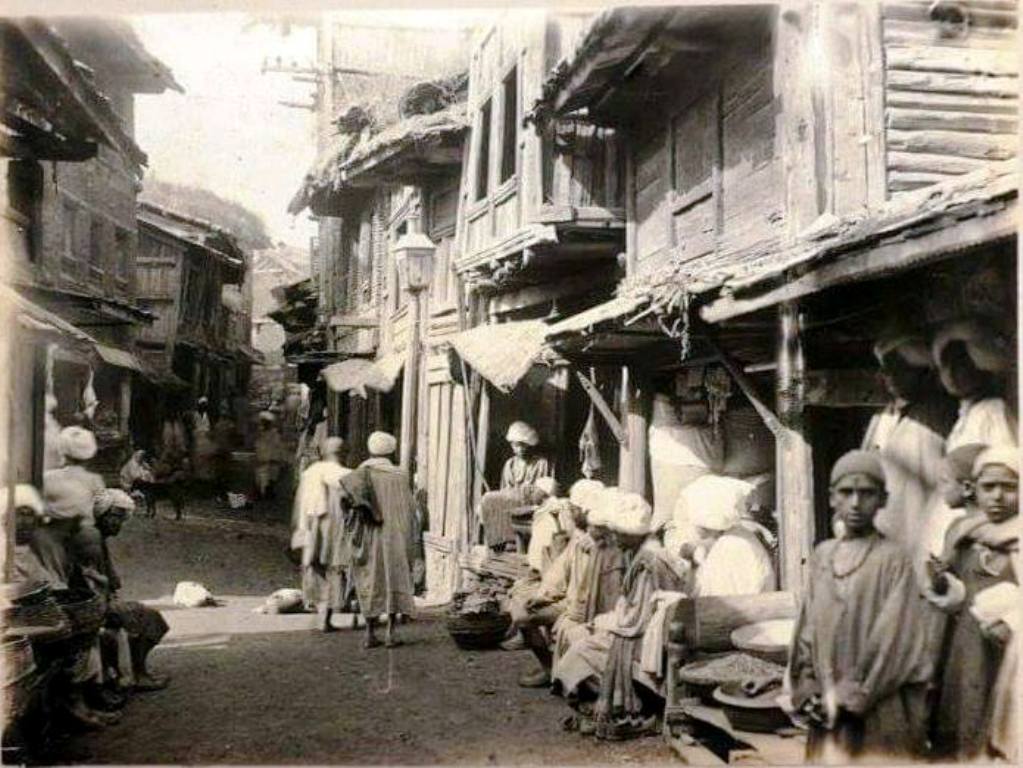

Bernier proceeds to extol Srinagar as emblematic of the valley’s cultivated beauty, strewn as it was with lush orchards, paddy fields and quaint hamlets along the riverbanks. He admires aspects such as the king’s Shalimar pleasure gardens with their tree-lined canals and fountains, the royal Takht-i-Sulaiman hill crowned with ancient Hindu and Muslim monuments, as well as the bustling timber houses and floating gardens on the iconic Dal Lake. Captivated by this “enchanting scene,” he argues passionately that Kashmir merits its exalted sobriquet as the “paradise of the Indies” and should rightfully hold Mughal sway over the neighbouring mountain kingdoms as far as Ceylon.

Beyond panoramas, Bernier’s account also spotlights the industrious character of Kashmir’s inhabitants, especially commending their agricultural bounty. He notes approvingly their ingenious irrigation systems allowing cultivation even on the valley’s hills and their prolific production of rice, saffron, fruits and vegetables. However, he singles out the manufacturing of Pashmina wool and shahtoosh shawls as Kashmir’s prime glory, which generates vital trade. He describes different types of superior quality Kashmiri shawls, patterned and fringed, fashioned from the fine wool of native goats or imported from Ladakh and Tibet. Though competitive copying was attempted in Mughal capitals like Agra and Lahore, Bernier declares none could match Kashmir’s artisanry, colour mastery or the secret locked in its waters.

Anthropological Adventures

Another dimension emphasised is the distinctive appearance and wit of the Kashmiri populace. Bernier asserts they have fairer complexions and more European-style features than other Indians, with the striking beauty of even lower-class women. He playfully recounts his covert efforts to catch glimpses of the city’s exquisite but cloistered ladies through tricks like distributing sweets via a learned guide. These intelligent, poetic people also earned his admiration for technological and literary skills seen in carved woodwork, eloquent poetry, and artistic talent comparable to Persians. Since intermarriage with beautiful Kashmiri women was coveted to preserve the “white” Mughal lineage, Bernier cheekily argues Srinagar likely boasted ladies as lovely as any European belle.

Blending factual observations with sentimental impressions, he spotlights its unparalleled aesthetic charm and prosperous economy in a way that powerfully justifies its intervening Mughal and Afghan conquerors. Though a colonial European lens mostly colours his perspective on stereotypical Oriental themes like feminine beauty or royal indulgence, Bernier, at times, also demonstrates genuine openness.

He presents Kashmiris as honourable partners in trade and culture with admirable qualities meriting respect. Thereby, while undeniably an outsider, he creates an immersive eyewitness account that largely transcends stereotyping to recognise Kashmir’s multidimensional reality on its terms. Ultimately, through this lens of a traveller enraptured by Kashmir’s beauty over three centuries ago, 21st-century readers gain insight into its enduring, if imperilled, magic.

“It’s (Kshmir’s) physiognomy is perfectly Armenian, the men being very fair, with reddish hair and blue eyes…I was amazed to see a tall, handsome, white lad enter the little temple I have described, dressed as a woman.”

Bernier’s perspective remains philosophically detached as he explores the land “penned in between lofty mountains” where “opposite seasons are experienced within the same hour.” He climbs summits less for glorious vistas than to empirically deduce the cause of natural oddities, as with the intermittent sacred spring at Bawan: “Having made these observations, it occurred to me that this pretended wonder might be accounted for by the heat of the sun, combined with the peculiar situation and internal disposition of the mountain.”

The reader gets privy to his systematic hypothesis testing and elimination as he intrepidly surveys the area despite hazards and fatigue to reach this rationalist insight.

Likewise displaying only anthropological interest in the attention-seeking ‘hermit’ amidst Kashmir’s Wular Lake, Bernier pointedly declines to “fill up this letter by recounting the thousand absurd tales reported”.

Beyond busting supernatural myths, Bernier provides insight into the essence of Kashmir – the evocative vestiges of distant glorious eras contrasting with present decay and deprivation: “The wretched inhabitants of this charming country cluster, during summer, under wretched sheds of straw and sedges…enslaved and subjected to excess labour.”

Spaces apart, Bernier records help readers scale Kashmir’s passes and peaks and digress into Kashmir’s mythic origins. He sifts through poetic legends surrounding the Verinag Springs to unearth traces of a queen who adorned sacred fish with golden rings. Quoting local tradition, he resurrects the memory of a paradisical city drowned beneath the lake for its ruler’s sins. Such nostalgic episodes, like glimpses of forgotten grottoes and secluded vales, amplify the sublime mystique permeating his chronicle.

This sense of mystery also surrounds Bernier’s documentation of unfamiliar cultures, satiating his ethnological curiosity. He profiles polyandrous highlanders, likely Buddhist tribes and hill chiefs inhabiting virtually inaccessible republican mountain fastnesses. Though stymied from fully investigating these remote communities, his account fires the imagination, spurring interest in comprehensively charting Kashmir’s distinctive cultural mosaic.

Bernier recounts a story about a supposed miracle performed by some Muslim clerics involving a heavy stone. Bernier exposes this as a sham by detailing how he joined the group in trying to lift the stone and felt them secretly using more than just their fingertips. This episode establishes Bernier’s scepticism regarding superstitious claims and miracles, a mindset he brings to his documentation of Kashmir.

After departing the staged miracle, Bernier wanders the countryside, depicting sites like a spring whose ebullience purportedly increases with loud noises, though Bernier determines natural causes underlie its bubbling. He climbs mountains rife with flowers and glacial lakes, searching for a “grotto full of wonderful congelation,” but recedes once summoned back by his awaiting party.

In Search of Moses

The heart of the account examines Kashmiri heritage, especially possible Jewish ancestry. Prompted by inquiries from his friend, Bernier investigates claims of long-established Jewish communities possessing Old Testament texts. Though unable to validate such communities persisting, Bernier provides extensive evidence for prior Jewish presence.

He first notes the Jewish cast of features observed among frontier villagers. Corroborating this, he cites other Europeans struck by the same semblable. He also explains the prevalence of the name Mousa, meaning Moses, in the region’s capital city. Ancient traditions holding that Solomon visited Kashmir and directed the construction of a throne structure offer further clues. Most compellingly, widespread belief holds that Moses himself died near the city, with his tomb located less than a league away.

While Bernier cannot definitively trace Kashmiri Jews back to Biblical times, he marshals considerable indications of early Jewish influx, with religious deviation occurring over prolonged ages of isolation. He suggests conquest or conversion to Islam during Medieval periods may have assimilated remaining enclaves into the broader population. Nonetheless, he strongly disputes that no basis exists for supposing Jewish residence in the distant past, reinforced by the ethnocultural clues still evident among modern Kashmiris.

Beyond the Jewish question, Bernier relays recent historical events related to him by local informants. One man describes fleeing Mughal persecution by finding refuge in remote mountain settlements, where he was welcomed and community elders offered their daughters to seed future generations with his noble bloodline. This paints a portrait of insular highland peoples fiercely protective of their ancestral lands.

Bernier also recounts political turmoil in ‘Little Tibet’ (Baltistan) and its entanglement with competing Kashmir and Mughal interests. Intriguingly, he provides early European notice of polyandry customs whereby brothers jointly marry one wife. He further notes the prevalence of Shia Islam in Little Tibet, reflecting Persia’s religious and cultural influence reaching across the inner Asian highlands.

The Conclusion

Throughout these anecdotes, Bernier exhibits scholarly yearning to elucidate blurry ethnogeography by querying travellers from exotic frontiers. He gains snippets of knowledge about trade routes leading over majestic mountain ranges towards China, legends of a once wealthy but long-vanished underwater temple city, and caravans burdened with musk, wool, and precious minerals.

Bernier’s account reveals Kashmir as the meeting point of myriad cultures, faiths, and mythologies – an enigmatic setting rich in history and manifold identities. Through careful analysis and reasoned speculation, Bernier unravels strands of the region’s intricate tapestry to provide enticing glimpses into its past as a nexus of civilizations. Within his questing narrative, transporting readers to the far reaches of the known world, lay the beginnings of an empirical sensibility that helped expand early modern Europe’s conception of itself.

Bernier’s travelogue recounting his curious forays into the Kashmir of bygone eras remains intellectually daring and evocative centuries later. Masterfully contextualizing its traditions and hardships, splendour and contradictions, Bernier makes a spellbinding journey to 17th-century Kashmir equally tantalising in the present. The seductive, elusive quality that so entrances him continues to entice and beguile today’s readers, inviting them to immerse themselves in his vivid chronicle while kindling an imperative to rediscover the real Kashmir behind the exotic phantasm.

MAGNIFICIENT POWERS OF OBSERVATION AND INCISIVE DESCRIPTION OF MINUTE DETAILS HAVE BEEN PROVIDED BY BERNIER

TO SHOW THE WORLD OF HEAVEN ON EARTH.THANKS.