In her book, A Fate Written On Matchboxes, Hafsa Kanjwal, a Kashmir-origin American scholar, revisits the structure and systems in the decade-old rule by Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, who succeeded Sheikh Abdullah after the later was deposed and arrested. Muhammad Nadeem sees the book as a gripping narrative of the era that Kashmir has always loved to talk in hissed tones

Hafsa Kanjwal’s A Fate Written on Matchboxes presents an analysis of state-building in Kashmir during the early decade’s post-1947.

The key focus of the book is the examination of the ‘paradox’ of development and progress under Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad in the 1950s. Bakshi’s government played a crucial role in the integration of Jammu and Kashmir through state-building practices, while simultaneously overseeing increased modernisation in the region. Consequently, the book offers a critical lens to understand state-building in contested political contexts associated with postcolonial nation-state formation.

Hafsa explores the “politics of life” that shaped Bakshi’s governance, which emphasised empowerment, development, and meeting basic needs as a means to cultivate loyalty to India and suppress political dissent. Despite cultivating secular Muslim identities, policies continued to fuel resentment among Kashmiris, and the pursuit of “normalcy” necessitated the suppression of opposition. By analysing this emotional integration policy under Bakshi, the book exposes the assimilation logic at play, which has long sought to eliminate Kashmiri identity and notions of belonging since 1947.

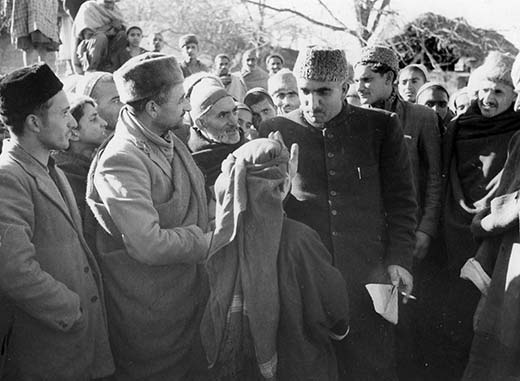

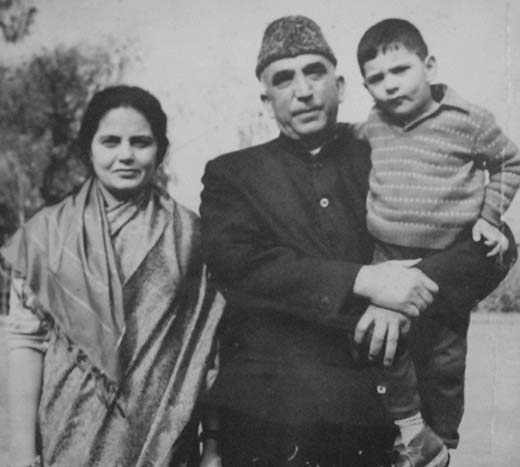

The Rise to Power

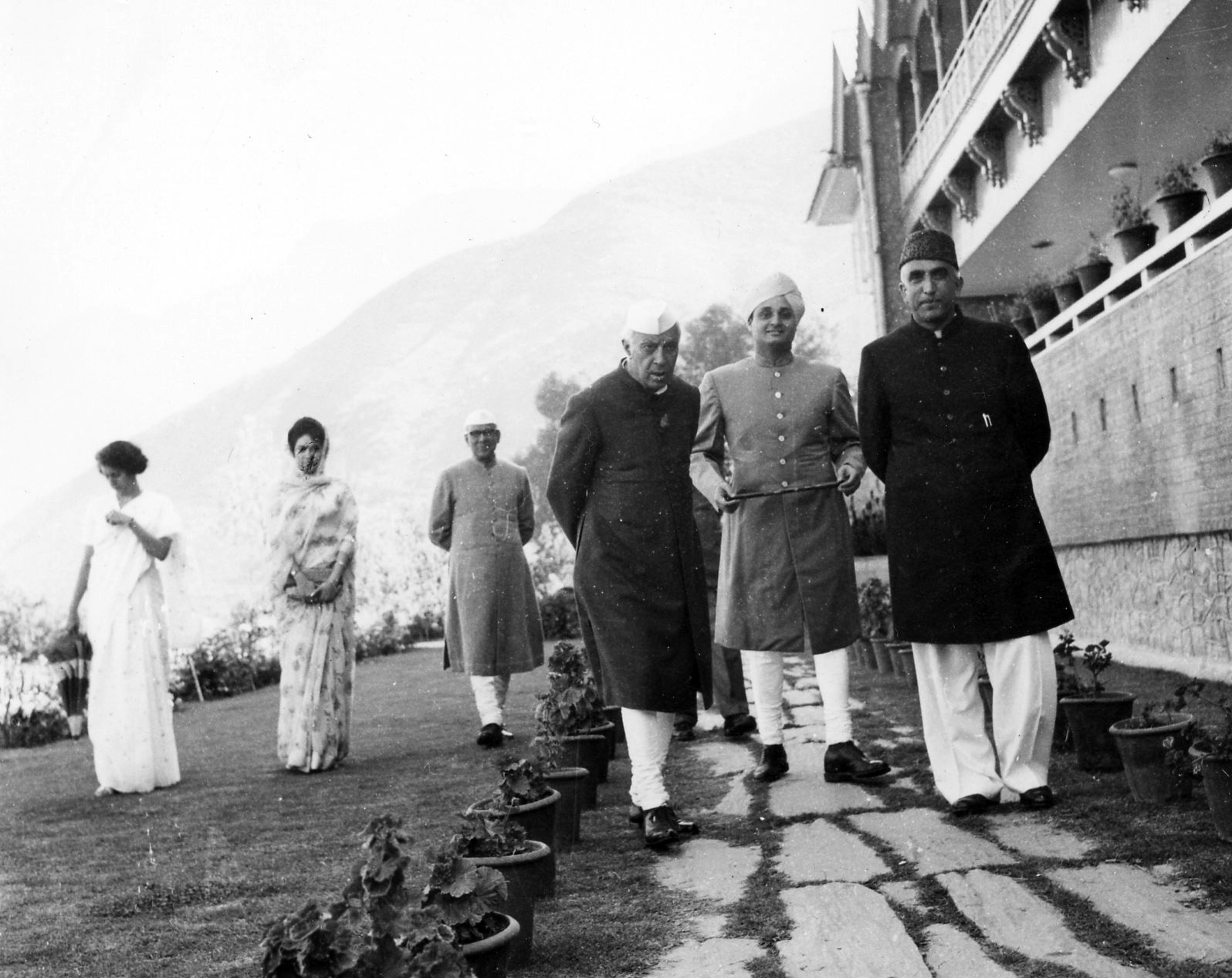

In Chapter 1, the author provides critical background and context for comprehending Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s rise to power and his subsequent state-building project in Kashmir. The chapter unfolds chronologically, detailing the political developments and challenges faced by the region from the late Dogra period through Sheikh Abdullah’s rule after accession.

The initial section delves into the despotic rule of the Hindu Dogras over a marginalised Muslim majority population. The repressive taxation, discriminatory land policies, and religious bias inflicted immense hardship on Kashmiri Muslims. This oppressive environment fuelled the emergence of political movements like the Muslim Conference and the National Conference under Sheikh Abdullah. The author highlights the complexities of political mobilisation in Kashmir, which were marked by intra-Kashmiri tensions along religious, class, and regional lines. The significance of the nationalist Naya Kashmir manifesto of 1944 is acknowledged as foundational to the state-building visions of both Abdullah and later Bakshi, despite its incomplete implementation.

The subsequent section covers the tumultuous period surrounding the partition and the subsequent developments. Post-accession, Sheikh Abdullah’s interim government is depicted as politically and economically unstable, authoritarian, and nepotistic. Despite initially agreeing to Article 370, which was meant to safeguard Kashmir’s autonomy, Abdullah’s position weakened as India strengthened its hold on the region. His subsequent turn away from India resulted in his arrest and his replacement by Bakshi in 1953, facilitated by a Delhi-backed coup.

The Propaganda Blitzkrieg

In Chapter 2, the author offers observations on how Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s government in Kashmir effectively employed propaganda and media narratives to project a sense of “normalisation”. Following the 1953 coup against Abdullah, Bakshi faced a notable “crisis of legitimacy” both within Kashmir and on the international stage. As the author presents through archival evidence, prominent international newspapers criticised Delhi for forcibly removing Sheikh Abdullah, with Life magazine even depicting troops suppressing pro-Abdullah protestors in Kashmir. However, in a remarkable turn of events, just a few years later, accounts of Bakshi’s Kashmir in the media were predominantly positive. Journalists began to report on progress in various sectors, including land reform, education, tourism, transportation, employment, irrigation, agriculture, industry, and food availability.

The chapter then traces how Bakshi’s government actively invited Indian and international media to showcase development projects and meet with Bakshi himself. The Department of Information went to great lengths to provide journalists with favourable accommodations and additional amenities, even establishing a special “Entertainment of Press Correspondents” fund. Consequently, starting in 1955, the American and international press became significantly more complimentary towards Bakshi’s Kashmir, focusing on the narrative of progress and normalisation.

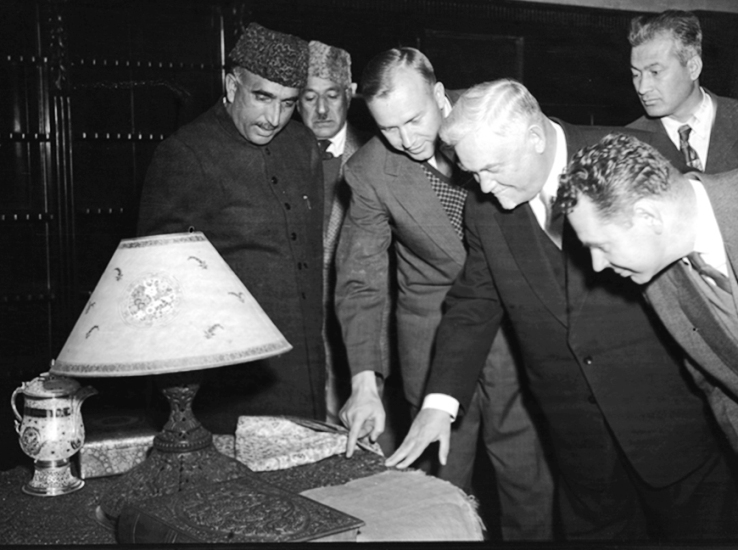

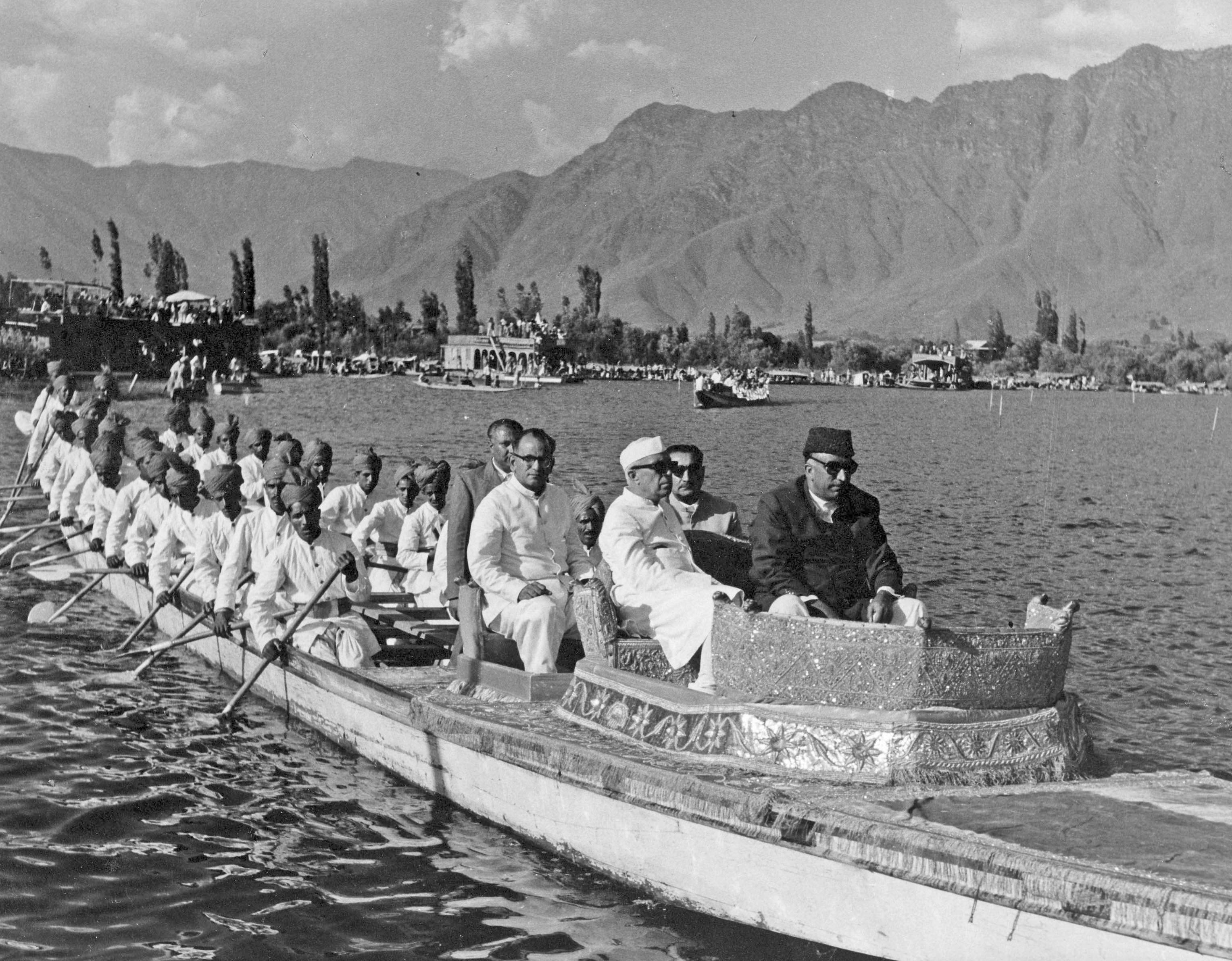

Furthermore, the author offers an analysis of Bakshi’s strategic efforts to influence Muslim-majority countries and the Soviet Union. Notably, accounts from Indonesian journalists who had been on state-guided tours were found to be “resoundingly pro-Bakshi”. Additionally, the chapter highlights the pivotal 1955 visit of Soviet leaders who declared Kashmir an internal affair of India, which vividly demonstrates Bakshi’s shrewd diplomacy in managing international perceptions.

Tourism and Cinema

Chapter 3 presents an analysis of how tourism and cinema were strategically employed to territorialise Kashmir. The chapter argues that Bakshi’s government, meticulously crafted representations to portray Kashmir as a ‘paradise’.

A central insight in the chapter is how Delhi facilitated tourism by providing the necessary transportation and infrastructure for tourist travel, while also constructing specific imaginaries that tourists were expected to carry back with them. By removing the permit system and enhancing infrastructure, the number of tourists significantly increased, with 63,370 domestic and 11,190 foreign tourists visiting Kashmir in 1960, compared to only 9,330 domestic and 1,250 foreign tourists in 1951.

Equally compelling is the exploration of how tourist materials deliberately radicalised and feminised Kashmiris, often portraying them as “fair of complexion” and using gendered tropes to depict the land’s fertility. Meanwhile, the representations of Kashmiris were relegated to a premodern status, presenting them as awaiting Delhi’s modernising largesse. The chapter further delves into the rise of Bollywood’s ‘Kashmir obsession’ in Technicolor films, providing millions of Indians with a virtual ‘visit’ to Kashmir. However, the author notes that these films remarkably erased Kashmiris from their narratives, turning the region into nothing more than an exotic backdrop.

The author’s analysis sheds light on the complexities of the representations used to construct and control narratives surrounding Kashmir.

The Economic Challenges

Chapter 4 provides an exploration of the economic challenges and compulsions that drove state-building in Kashmir post-accession. The chapter reveals how developmentalism was strategically utilised by Bakshi to manage political instability.

Initially, Sheikh Abdullah aimed to maintain financial independence for Kashmir by broadening the state’s tax base instead of relying on external assistance. However, the National Conference government faced crises due to the lack of trade routes after partition and the burden of taxes on an agrarian economy. To stabilise the government politically, land reforms were implemented, benefiting the rural base of Abdullah’s government. Nevertheless, the quest for financial autonomy proved untenable, as various officials of the Kashmir government sought greater financial integration with the union for practical purposes.

Upon arresting Abdullah, Bakshi immediately placed economic development at the centre of his policy speech as the solution to political problems. Financial integration became crucial to fulfil promises of modernisation. As a result, Bakshi was able to secure grants from the federal government to implement development policies in Kashmir, and customs duties were removed to facilitate trade.

The chapter offers a critical analysis of the developmental policies pursued under Bakshi, revealing the tensions between short-term political imperatives and long-term economic growth. Bakshi aimed to appease the peasantry by abolishing the unpopular mujawaza system and securing federal rice subsidies, adopting a “politics of abundance” in contrast to austerity discourses in the mainland. However, the reliance on food imports failed to achieve the manifesto’s goal of self-sufficiency, and the lack of significant industrial development resulted in growing dependence on grants from Delhi. Infrastructure projects like the Banihal Tunnel successfully integrated Kashmir physically and emotionally with India.

While acknowledging that Bakshi’s developmentalism had real intentions to modernise and empower Kashmiris, the chapter also highlights the limitations imposed by aid dependence and political motivations, which hindered substantial economic expansion. The chapter also delves into governance issues and corruption in Kashmir under Bakshi’s leadership. It points out how patronage and corruption became ingrained as Bakshi centralised control over permits, loans, and contracts to secure political loyalty. Newspapers criticised the widespread nepotism, bribery, and misuse of development funds by officials, though an anti-corruption commission formed was later suspended.

The Education Makeover

Chapter 5 presents an analysis of the educational reforms in Kashmir and how they shaped the construction of a modern, secular Kashmiri subjectivity. The chapter delves into the historical context, particularly focusing on the lack of educational access for the Muslim majority under Dogra rule and the demands for educational reforms by emerging Muslim leadership. It emphasises the role of education as a major grievance of Muslims and underscores the goal of mass education in the vision for a new Kashmir.

The chapter highlights how education policies under Bakshi aimed to develop well-rounded, productive citizens who could contribute to the economic development and modernisation of Kashmir. The curriculum was designed to include vocational training, health and hygiene, civic duty, and pride in the Naya Kashmir programme. Extracurricular activities, such as sports, arts, and social service projects, were encouraged to instil discipline, nationalism, and communal harmony. Educational tours were arranged to expose students to places and people outside Kashmir, fostering effective ties with India.

The author argues that these policies enabled the state to shape Kashmiri identities and maintain social control, especially over the youth. The focus on extracurricular activities and emotional integration with the union allowed the government to construct modern, active, and disciplined national subjects. The chapter also points out how the government sought to contain political consciousness and activism among the youth through such measures.

Furthermore, the author discusses how the government’s attempt to promote secularism in education inadvertently led to religious tensions. The categorisation of students and teachers based on religious affiliation, as well as the emphasis on certain medieval poets and rulers, sparked criticism and polarisation. Critics argued that the government’s secular education model eroded Muslim identity and morality, leading to the establishment of private Islamic schools.

The chapter also delves into the debates over language policy in Kashmir’s education system, specifically the shift from Kashmiri to Urdu as the primary medium of instruction. It highlights multiple factors behind this shift, including administrative convenience and the aspirations of the upwardly mobile Muslim bureaucracy and middle and lower classes. Urdu’s perceived prestige and mobility also played a role in its promotion.

The Culture Campaign

Chapter 6 delves into the rich cultural and literary landscape of Kashmir. The author highlights the historical context of the rise of progressive and leftist thought in Kashmiri cultural production during the early twentieth century, particularly under Dogra rule. Poets like Mahjoor and Azad, inspired by leftist movements like the Progressive Writers Association wrote about the plight of Kashmiris under the Dogras. The National Conference mobilised the Cultural Front to spread socialist propaganda through art and literature during the anti-Dogra movement. However, the author also notes that not all writers supported the post-1947 political order, with some, including Mahjoor, expressing discontent through satirical poems criticising poverty and repression under Abdullah’s leadership.

The chapter then explores how Bakshi co-opted the cultural intelligentsia of Kashmir into the state bureaucracy to legitimise his rule. He provided patronage to writers and artists, commissioning works that promoted government narratives and hiring them for cultural institutions he established. This bureaucratisation was, however, contested, with some writers critiquing artists’ new establishment role.

Bakshi utilised poets to write laudatory poems performed at cultural events, praising his “benevolent and progressive rule.” He hired artists for various projects, bringing them into the state-building project, but this also elicited resistance. Some writers, like Nadim, grew critical, suggesting that money was used to lure artists into supporting Bakshi, and they criticised the flattery and sycophancy among artists.

The analysis then delves into the ways some Kashmiri writers, like Akhtar Mohiuddin, found subtle ways to critique the state and society despite being incorporated into government cultural projects under Bakshi. These writers explored themes like greed, loss of values, and corruption in their fiction, indirectly commenting on the implications of Bakshi’s politics of life. Mohiuddin’s fiction sought to uncover the compulsions and helplessness that shaped people’s actions under occupation without passing moral judgments. His works depicted complex inner worlds, providing insight into the “compulsions to compromise” faced by Kashmiris.

In Mohiuddin’s fiction, such as his novel Doad wa Dag and the story I Can’t Tell, he explored characters driven by various motivations, yet seeking redemption amidst society’s crises. The story I Can’t Tell reveals how poverty and political turmoil led a man to become an informer for Bakshi’s government, reflecting the helplessness prevailing in society.

The chapter illustrates how the literary and cultural scene in Kashmir remained diverse and nuanced under Bakshi’s rule, with writers expressing their complex negotiations between conformity and resistance. Some writers subtly contested official narratives and provided critical counter-narratives, uncovering the implications of Bakshi’s rule, and complicating simplistic notions of state power and propaganda.

An Era of Oppression

Chapter 7 provides an examination of the oppressive state machinery deployed in Kashmir post-1947. It focuses on the emergence of an authoritarian regime under Bakshi in the 1950s and 1960s, who ruled after the arrest of Sheikh Abdullah.

The chapter reveals the extensive surveillance and repression apparatus established by Bakshi to crush political dissent. The use of draconian laws such as the Public Security Act and Preventive Detention Act, allowing arbitrary and indefinite detention without trial, is highlighted. The brutality of police units like the Peace Brigades, which employed violence and torture against dissidents, is also exposed. The atmosphere of fear created through the use of spies and informants further emphasises the repressive nature of the state.

The chapter paints a powerful portrait of authoritarian governance in Kashmir. It highlights the permanent crisis mentality cultivated by the surveillance state.

The chapter offers a compelling scholarly analysis of a turbulent period in Kashmir’s modern history, shedding light on the oppressive state apparatus and the impact it had on dissent and political opposition in the region.

Conclusion

The conclusion of the book provides a comprehensive synthesis of the contested legacy of Bakshi in Kashmir.

The author highlights Bakshi’s approach of indirect governance through a local intermediary as a strategic move. His politics of life, which emphasised development, education, and cultural policies, served to create a Muslim middle class that became reliant on the state. This dependence on the government helped reconcile people’s economic aspirations with their political desires, enabling India to maintain a semblance of stability in the region.