Mehmood Gaznavi attempted to wrest Kashmir in the eleventh century twice and failed. The failed invasions, however, gave the Gaznavid court a lot of information about the economy, geography, politics and society of Kashmir. One of the beneficiary court scholars was al-Biruni, who gave detailed and unbiased information about the Kashmir of Diddha, Latadatiya and Sangramadeva, writes Muhammad Nadeem

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973-1048 CE) was a Muslim scholar and polymath who made significant contributions in diverse fields like physics, mathematics, astronomy, and natural sciences. He also distinguished himself as a historian, chronologist, linguist, and world’s first anthropologist.

Al-Biruni was born in Khwarazm (now falls in Uzbekistan and partly in Turkmenistan) in 973 CE. He likely started his studies at an early age under the famous astronomer and mathematician Abu Nasr Mansur and was probably engaged in his scientific work from around the age of 17. By 995 CE, al-Biruni had already written works on cartography and map projections.

Due to civil wars in the Islamic world in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries, al-Biruni had to flee his homeland around 1004 CE. His exact whereabouts in this period are unknown, but he likely lived in poverty for some time. He interacted and worked with other astronomers like al-Khujandi during this period.

Subsequently, al-Biruni travelled extensively, as indicated by the astronomical events he described from different places. Around 1004 CE he returned to his homeland where the ruler Abu’l Abbas Ma’mun supported his scientific endeavours – he built an instrument to observe solar transits and made 15 observations. However, after al-Ma’mun’s execution, al-Biruni again had to leave the region.

In Captivity

Al-Biruni’s capture in 1017 CE by Mahmud of Ghazni (Gaznavi) resulted from a complex interplay of political conflict, military invasion, and the scholar’s intellectual standing. Ghazni, a Turkic ruler, invaded Khwarezm, Al-Biruni’s homeland, destabilising the region. Due to his family’s influential positions and his association with the ruling elite, Al-Biruni became a target for the invading forces. The circumstances of his capture remain unclear, with suggestions ranging from being taken alongside others during the invasion to being specifically sought out for his scholarly reputation, possibly while travelling.

Al-Biruni’s compelling scholarship played a pivotal role in his capture, as Mahmud of Ghazni recognised the scholar’s value and transported him to Ghazni. Contrary to harsh treatment, Al-Biruni was respected and provided resources for scholarly pursuits. Despite being technically captive, he flourished intellectually in Ghazni, gaining access to libraries and scholars. The capture, traumatic yet transformative, afforded Al-Biruni unique opportunities to explore diverse cultures and religions. The episode, marked by political intricacies, familial affiliations, and scholarly renown, became a turning point in Al-Biruni’s life, leading to enduring contributions across various fields of knowledge.

As a captive of the Mahmud Ghazni, he visited India in 1018 CE and likely studied original Indian texts, translating some into Arabic. His observations about Indian religion, culture and science were recorded in his famous work Tarikh al-Hind. With Mahmud’s death, his son Mas’ud treated al-Biruni better and allowed him to travel freely.

Indological Odyssey

As part of the mobile court of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni (998–1030), al-Biruni spent over a decade travelling widely across northwest India, from modern-day Afghanistan to the Punjab. His first-hand observations on the geography, history, and culture of medieval India, recorded in magisterial works like Tārīkh al-Hind (History of India) and other works on Tarikh–al-Hind, have justly earned him recognition as an early pioneer of Indology.

His detailed discussions of Kashmir in these texts demonstrate his position as a discerning collector of information on the region’s past.

Rather, he also relied extensively on Sanskrit scholars and Brahmins encountered in Punjab and the volatile Kashmir borderlands for geographical and cultural insight into Kashmir. His extensive exchanges with “Kashmirian scholars” and references to specific Kashmiri intellectual figures like Ugrabhuti confirm his privileging of Hindu informants from Kashmir and wider India. Given barriers to direct access, al-Biruni’s understanding of eleventh-century Kashmiri society derives from his experience as well as the interpretative lens of these peripheral intermediaries and unmediated observation.

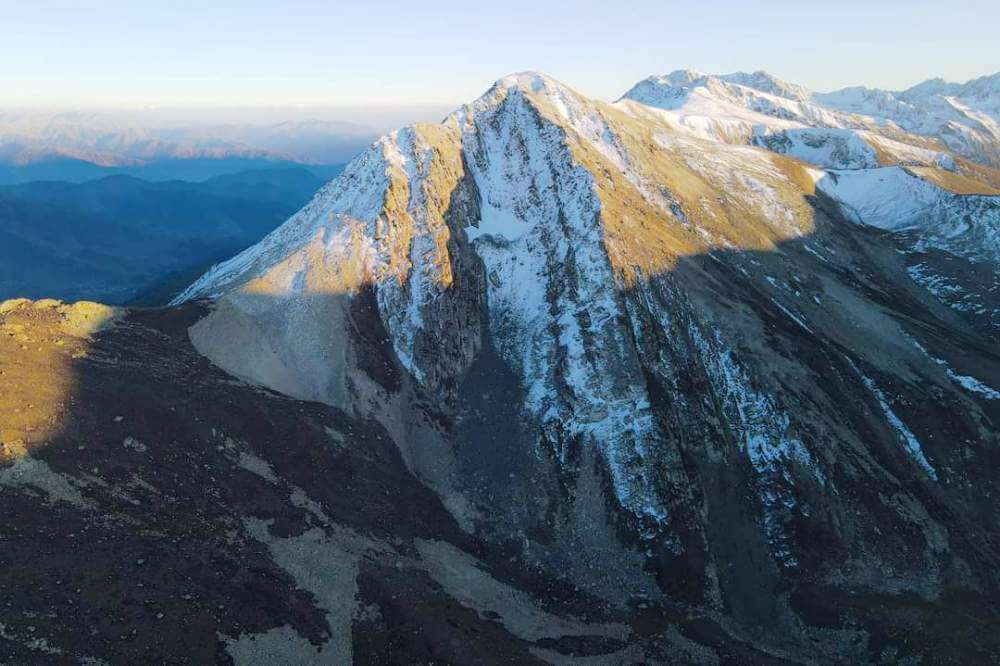

In his geographical appraisal of the region, al-Biruni shows cognisance of Kashmir’s distinctive topography and geostrategic position along vital trade corridors connecting the Indian subcontinent with Inner Asia. He aptly characterises Kashmir as a “plateau surrounded by high inaccessible mountains”, which facilitated the valley’s historical autonomy but also isolation from external forces.

Al-Biruni demonstrates familiarity with important passes like the Zoji La, which he identifies as a gateway “connecting the Kashmir valley with China and Tibet via Ladakh”. His labelling of neighbouring mountain chiefs as the Bolor Shahand Wakhan Shah accurately correlates with known adjacent principalities in Baltistan and Wakhan along Kashmir’s volatile western frontiers.

Furthermore, al-Biruni notes Kashmir’s historic resistance to the outside incursion, stating “they take much care to keep a strong hold upon the entrances and roads leading into it. In consequence, it is very difficult to have any commerce with them” (Tārīkh al-Hind). This elucidates Kashmir’s seemingly anomalous preservation of independence under Hindu rulers in the era of Sultan Mahmud, who despite numerous attempts remained unable to conquer the valley.

Kaleidoscope of Kashmir

In chronicling Kashmir’s early medieval Hindu rulers, al-Biruni demonstrates substantial reliance on Sanskrit sources and oral accounts communicated by his Kashmiri interlocutors. He refers to the Hindushahi king Muttai Lalitaditya Muktapida (724-760 CE), said to have “gained a victory over the Turks” towards forging a pan-Indian empire (Tārīkh al-Hind). Furthermore, al-Biruni documents more contemporary Kashmiri sovereigns like Queen Didda (980-1003 CE) and Sangramadeva (1003-1028 CE), the latter aligned with timeframes for his research in northwest India (Tārīkh al-Hind).

Al-Biruni reserves special praise for the Hindushahi ruler Anandapala (1002-1010 CE), highlighting a story that “shows that he was not only a learned man himself but also patronised the learned and encouraged learning” (Tārīkh al-Hind). This positive portrayal accords with the pro-Hindu Shahi bias of the Rajatarangini chronicle, reflecting al-Biruni’s internalisation of courtly Sanskrit perspectives on Kashmir’s past communicated by his Brahmin contacts.

Besides court history, al-Biruni exhibits admiration for the scientific traditions of medieval Kashmir, frequently citing astronomical texts and mathematical authorities hailing from the valley. Kashmir-centric scientific works listed by al-Biruni feature titles like Karaṇa-sâra, Sarvadhara and an unnamed Calendar from Kashmîr, alongside repeated references to seminal Kashmiri scientific thinkers, including Mahadeva Chandrabija and Utpala. The disproportionate prevalence of Kashmiri authors in al-Biruni’s formidable scientific source list signals the uniquely high regard for Kashmiri scholarship within the larger tradition during the eleventh century.

Moreover, al-Biruni reproduces a foundation story tracing the genesis of the indigenous Brāhmī script (termed Siddhamātṛkā) to Kashmir, elucidating his access to seminal Kashmiri literary traditions beyond strictly technical material (Tārīkh al-Hind). While al-Biruni relied substantially on Punjab and Tibet for precise cartographical data, these repeated references nevertheless demonstrate his genuine scholarly interest in – and deference towards – Kashmiri scientific material circulating contemporaneously in northwest India.

Kashmir Geography

In Tarikh al-Hind, Al-Biruni highlights Kashmir’s strategic role in bridging Tibetan culture, Inner Asia, and the Indian subcontinent despite restricted access.

As al-Biruni states some of his geographical knowledge of the Indian subcontinent is derived from second-hand accounts and textual sources rather than autopsy.

“If the latitudes of places are known, and the distances between them have been measured, the difference between their longitudes also may be found…. We ourselves have (in our travels) in their country not passed beyond the places which we have mentioned, nor have we learned any more longitudes and latitudes (of places in India) from their literature,” he recorded in his seminal Tārīkh al-Hind. “It is God alone who helps us to reach our objects!”

Political History

In chronicling medieval Kashmir’s court history, al-Biruni also relies on Sanskrit sources and insights from Hindu informants. As outlined in Tārīkh al-Hind, Anandapala’s receptiveness towards the Kashmiri Sanskrit grammarian Ugrabhuti proves his exalted reputation as an exemplar of Hindu kingship.

“Among the conditions which a king has to fulfil we may mention that he should be accessible to his subjects… should have a kind heart for them and not disappoint anybody in his hopes…These qualities we find in most Hindu princes, e.g. in… Anandapâla,” al-Biruni has recorded in his Tārīkh al-Hind. “The following story from his life shows that he was not only a learned man himself but also patronised the learned and encouraged learning: Ugrabhûti had composed a short grammar called Sishyâhitâvṛitti for beginners, particularly for children. Anandapâla liked it highly and ordered that only this book should be studied by the children as an introduction, excluding all other books. The order became obligatory in Kashmîr.”

Al-Biruni’s valorisation of Anandapala for his discerning patronage of the Kashmiri grammarian Ugrabhuti mirrors eulogies for the Shahi dynasty found in the Rajatarangini. His laudatory tone indicates assimilation of the pro-Hindu tenor of Sanskrit sources on Kashmir communicated orally by his Brahmin contacts stationed along Kashmir’s frontiers. While he might not have directly visited the courts of Kashmir, al-Biruni’s accounts of prominent rulers like Sangramadeva and Anandapala are derivative of indigenous Persian perspectives circulating in the early eleventh century within reach of Ghaznavid domains.

Religion and Sciences

Moreover, beyond strictly technical material, al-Biruni reproduces Kashmiri literary origin myths like that of the indigenous Brāhmī script. As he notes, “The most generally known alphabet is called Siddhamâtṛikâ, which is by some considered as originating from Kashmîr, for the people of Kashmîr use it. But it is also used in Varânaṣî. This town and Kashmîr are the high schools of Hindu sciences”. His documentation of foundation stories linking the genesis of Brāhmī writing with Kashmir indicates genuine familiarity with – and deference towards – Kashmir’s prestigious Sanskrit literary traditions.

This conspicuous prevalence of Kashmiri scientific and religious authorities across al-Biruni’s writings elucidates Kashmir’s towering status as a centre of traditional knowledge systems during the late tenth century.

“The centres of Indian learning were Benares and Kashmir, both inaccessible to a barbarian like Alberuni, but in the parts of India under Muslim administration, he seems to have found the pandits he wanted, perhaps also at Ghazna among the prisoners of war,” Edward C Sachau outlined in India: An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, insisting Kashmir alongside Varanasi were the preeminent seat of classical learning “India, as far as known to Alberuni, was Brahmanic not Buddhistic.”

For all Kashmir’s defensive seclusion, he concedes its Brahminical culture sustained dominance as a pole of traditional Indian knowledge – one whose literary artefacts and specialist practitioners circulated widely despite political barriers, as evidenced by his substantial first-hand access across the Indo-Persian frontiers.

The Mediated View

In his introduction to Tārīkh al-Hind, al-Biruni acknowledges his descriptions of India’s religious traditions; sciences, culture, and history are fundamentally based on native guidance and independent deductions:

“… I am quite unable to traverse this road by my own independent investigation…If we entertain the wish to compare the intellectual power of the Hindus with that of the nations of antiquity, we must compare it with the intellectual power of the very ancient world,” he recorded in his Tārīkh al-Hind. “For the Hindus in their heyday were civilised peoples.”

This passage elucidates how al-Biruni’s influential portrayals of an exotic India for Persianate readers inherently filtrate through his cultivated Hindu interlocutors. Much as with Kashmir, he obtained knowledge of Indic scientific and cultural accomplishments at several stages removed – as prefiltered through the interpretative lens of accessible native intermediaries. While these highly mediated second-hand accounts sacrifice experiential authenticity, their very indirection paradoxically spotlights the agency of al-Biruni’s Kashmiri Brahmin and scholar informants in actively shaping enduring Persian visions of their homeland.

Conclusion

Abu Rayhan al-Biruni’s seminal Persian histories preserve the essential record and insight into a pivotal period in medieval Kashmir’s past. His discussions are remarkable for spotlighting the dynamic circulation of mobile Kashmiri scholars across porous political frontiers, securing the transmission of knowledge despite Kashmir’s defensive seclusion. Al-Biruni’s testimony endures among the most incisive early portraits of Kashmir – not in spite but fundamentally because of his strict reliance on indigenous intermediaries. Though not autoptic, it represents the refracted perspective of local Brahmins and religious specialists more accurately than any outsider could hope to match.