Islam’s controversial Sufi, poet and teacher Mansoor Al-Ḥallāj (858–922), who was brutally executed by the Abbasid caliphate for political reasons rather than his ecstatic utterances, is reported to have visited Kashmir at the fag end of the ninth century. Muhammad Nadeem looks at all possible historical resources to generate a detailed narrative of the historic visit

The mystical journeys of Mansur Al Hallaj have captured the imagination of Sufis and scholars for over a millennium. His wanderings took him across the Muslim world, from Baghdad to Mecca, Egypt to India. Among the many storied destinations of his travels, Kashmir holds a special place. Through scattered accounts, anecdotes, legends and debates, a picture of Hallaj’s time in this remote but spiritually vibrant region does emerge.

Kashmir and Al Hallaj

The connections between the life of Al Hallaj and Kashmir are tenuous despite imaginative stories linking the two. With scant evidence of his physical presence in Kashmir, his influence is better understood at the mythic rather than the historical level.

Tales of his travels to Kashmir represent him more as an archetype than an individual. In popular memory, Al Hallaj’s story symbolises the martyrdom of ecstatic divine love. Creative theorists and artists have woven Kashmir into this narrative for their spiritual purposes. Examining how his myth was adapted by Kashmiri thinkers reveals more about their ideals than any verified impact of the historical Al Hallaj himself.

The most detailed accounts of Al Hallaj’s travels to Kashmir occur in Persian-language Sufi literature composed centuries later under patronage from regional dynasties like the Khwarazm Shahs, Delhi Sultanate, and the Mughals. The need to integrate Kashmir into the Islamic worldview helps explain its prominence in these mythic tales. While pre-modern in origin, this literary lore contributed to the modern claim that Al Hallaj visited Kashmir. But deconstructing the stories reveals imaginative motives beyond historicity.

Hallaj’s Life and Travels

Abu Al Mughith Al Husayn bin Mansur Al Hallaj was born around 858 CE in Fars, Persia to a Sufi cotton carder (Hallaj meaning “cotton carder” in Arabic). From an early age, he displayed mystical tendencies, including periods of seclusion and fasting. He eventually became a student of the renowned Sufi master Sahl Al Tustari. However, Hallaj fell out with his teacher due to differences in their mystical doctrines and practices.

Hallaj believed in an ecstatic union with God, uttering the words Ana Al Haqq (I am the Truth). This brought accusations of blasphemy from orthodox authorities. Hallaj subsequently embarked on extensive travels across the Middle East, North Africa, Turkestan and India. His wanderings appear to have begun around 890 CE when he left his native Persia.

“It is probable that Hallaj passed directly from India to Khorâsân, going up north, first by the valley of the Indus, and then Kashmir, which was then pagan,” Louis Massignon, the pioneering French scholar on Hallaj, wrote in the first volume of his seminal work The Passion of Al-Hallaj, Mystic and Martyr of Islam. “It is at least what can be inferred from the following apologue.”

This indicates that Kashmir was a destination on Hallaj’s wide-ranging spiritual journeys across the Islamic world and lands beyond. He seems to have travelled through India extensively before arriving in Kashmir. Massignon cites his presence in Gujarat, where Hallaj had interactions with local polytheists. He travelled from the port city of Daybal (near modern Karachi) up the valley of Indus to the town of Multan, before arriving in Kashmir.

The Importance of Kashmir

What attracted Hallaj to Kashmir tucked in the Himalayas? Kashmir had an ancient history as a centre of religious thought and philosophical inquiry. Hinduism, Buddhism and an eclectic mix of faiths flourished together in the region. The valley was also geographically on the route connecting Persia and Central Asia to India. Muslim rule had arrived in Kashmir at the beginning of the eighth century, barely 150 years before Hallaj’s travels. The Muslim sultans allowed a spirit of religious pluralism to continue, with Buddhist scholars participating in theological debates. Hallaj likely sought exposure to this diversity of cultures and faiths.

The open atmosphere also encouraged scientific inquiry, with an observatory operational in Kashmir during Hallaj’s lifetime. The prevalence of philosophy, astronomy and mysticism would have made Kashmir a fertile ground for Hallaj’s eclectic blend of knowledge. His mystical ideas resonated with the introspective spiritual traditions that had taken root here over centuries.

Louis Massignon also suggests that Hallaj met figures versed in mystical arts, which may have contributed to the legends about him performing esoteric miracles. As Massignon puts it: “Hallaj’s visit to Qashmir proves that he made inquiries of a doctrinal nature in India, and did not only look for more or less miraculous techniques.” So, while Hallaj was not necessarily seeking occult rituals, Kashmir’s position as a repository of ancient wisdom could have proved useful for him.

The Date

When exactly did Hallaj visit Kashmir? Massignon cites the meeting between Hallaj and the Sufi Shaykh Abdullah Al Turughbadhi after his return from Kashmir to the town of Tus. This encounter reportedly took place around 896 CE. Massignon concludes: “We know, through Turiighbadhi, that Hallaj returned from Qashmir (via Kabul-Balkh) when he received him (around 284/896 at Tus).”

Therefore, scholarly consensus places Hallaj’s stay in Kashmir around 890-896 CE, in the interim period between his travels across India and his return to Persia via Afghanistan. He is unlikely to have spent more than a few years in Kashmir itself, considering he passed through on his longer journey across the subcontinent. The dating ties in with the rule of Hindu King Shankaravarman of the Karkota dynasty, under whose relatively liberal regime such visits by Muslim mystics were still possible.

Anecdotes of Visit

Much of what we know comes from anecdotes written several centuries after his death. The most famous account involves Hallaj witnessing a mystical rope trick upon arriving on the shores of India:

“He set off then for India and I accompanied him as far as India. Once there, he asked for information about a certain woman, went to find her, and chatted with her. She arranged to meet him the next day; and the next day, she left with him for the sea coast, with a rope twisted and tied in knots, like a veritable ladder,” the famous book the Kitab al-‘uyun wa’l-hada’iq fi akhbar al-haqa’iq has mentioned. It is an Arabic chronicle covering Muslim history up to 961 CE. Its author is not known but the text was likely written in the late eleventh century. “Once there, the woman said some words, and she climbed up this rope – she placed her foot on the rope, and she climbed, so much so that she disappeared from our sight.”

This fantastical tale seems metaphorical, with the disappearing rope symbolising esoteric Indian rituals bearing little resemblance to reality. Attar’s 13th-century Sufi biographies place this incident in Kashmir, but it might likely be an imaginative embellishment.

Another famous legend involves Hallaj arriving in the company of two black dogs, shocking onlookers used to his austerity: “Mansur Hallaj arrived from the city of Qashmir, dressed in a black qaba‘, holding two black dogs on a leash. The Shaykh said to his disciples: “a young man arrayed in this way is going to come; get up all of you, and go out to him, for he does great things.” Hallaj took the two dogs to a table with him and ate with them at the invitation of Shaykh ‘Abdallah Turughbadhi.

After the Shaykh bid him goodbye, his disciples questioned him: “Why do you let such a man who eats with dogs sit in your place, a passerby whose presence here renders our entire meal impure?” Shaykh Turughbadhi responded philosophically that the dogs represented base urges tamed and brought to heel. “These dogs were his self (nafs), they stayed outside him and walked after him; while our dogs remain inside ourselves, and we follow behind them,” the Shaykh said, “This is the difference between the one who follows his dogs and the one whom his dogs follow.”

This enigmatic apologue that reportedly took place at Tus, seems more metaphor than history, casting light on Hallaj’s mystical philosophy. Some, including Attar, adding to the legend of Hallaj, site the tale in Kashmir.

While these stories may contain more fiction than fact, they inspired later thinkers like Muhammad Iqbal to celebrate Hallaj’s Kashmir connection.

Connections with Kashmiri Mystics

Although hard evidence remains scarce, Hallaj’s relationship with Kashmir lived on through the region’s Sufi orders. The order of the Sufi saint Syed Ali Hamadani, who travelled from Persia to Kashmir in the 14th century, shows traces of Hallaj’s influence.

The scarcity of factual records of Hallaj’s actual time in Kashmir is understandable, given the remoteness and volatility of the region in that era. But the persistence of his presence in legends, tales and later Sufi connections shows that his mystical wanderings left a lasting imprint.

Almost a millennium later, Kashmir still cherishes its connection – especially in sufi poetry that emerged from the valley for centuries in Kashmiri and Persian and even in Urdu – with the mystic who transcended boundaries of creed, culture, and geography in his personal quest for Truth.

Iqbal and the “Eastern Alchemy”

Another influential mythologizing of Al Hallaj and Kashmir occurred amongst the Indian Muslim intelligentsia of British colonial times. Poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal is exemplary, mentioning Al Hallaj in both his Urdu and Persian verse.

In his famous Javid Nama, Iqbal depicts Al Hallaj as an antecedent of Nietzsche’s rebelling against ossified religion in the name of spiritual self-realisation. Kashmir features in one section where Iqbal meets Sufis who share their esoteric wisdom from its picturesque valleys and rivers.

Iqbal’s romantic imagery serves to portray Kashmir as the serene abode of Islamic mystical knowledge. The landscape’s sublime aura parallels the Sufis’ inner enlightenment just as in Attar. Iqbal combines this idealised Kashmiri locale with veneration for Al Hallaj’s sacrificial quest for higher knowledge. Kashmir represents a mythic ancient source of primal Eastern wisdom, which Al Hallaj’s journey tapped for his revolutionary insights. Iqbal implies that communing with these esoteric roots could awaken the Islamic world from its slumber. So, Kashmir again becomes the mythic horizon where a visionary like Al Hallaj attains the profound realisation to transform society.

By transposing this orientalist myth of mystical Kashmir onto Al Hallaj, Iqbal suggests that the basis for revitalising Islam lies in recovering its connections with South Asian wisdom. The paradise of Kashmir symbolises this realm of forgotten metaphysical knowledge that could bridge religion and science in Iqbal’s view. Bringing Al Hallaj physically and spiritually into contact with Kashmir’s ancient wisdom helps make him an icon of Iqbal’s philosophic aspirations for an enlightened, dynamic Islam awake to its origins.

Later Life and Execution

After his long period of travels, Al Hallaj returned to his native Persia around 894 CE, staying for a while in towns like Nishapur. But his preaching had inspired mixed reactions everywhere he went, and he soon departed again for Baghdad and Mecca. After performing the Hajj for the second time, he returned to Baghdad around 898 CE and gathered many followers in the city.

However, his controversial claims angered orthodox Islamic scholars and political authorities. Around 900 CE, the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu’tadid ordered him arrested and questioned on accusations of heresy but later released him.

He continued public preaching and composed mystical works, likely including the Kitab al-Tawasin and Akhbar al-Hallaj during this time. But political tensions grew in the following years between mystical groups like Hallaj’s followers and orthodox scholars and judges backed by the Abbasid authorities.

In 909 CE, Al Hallaj was arrested again by the government on charges of heresy after the new caliph al-Muqtadir came to power. He was imprisoned for nearly a year before a long trial was conducted from 910-912 CE. The trial evoked significant debate and disagreement within the Islamic scholarly community. But under pressure from powerful officials like the Chief Qadi, Al Hallaj was prosecuted and found guilty of apostasy and blasphemy.

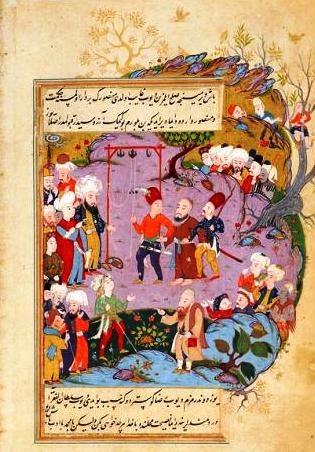

Finally, after years of imprisonment, Al Hallaj was publicly executed on March 26, 922 CE (27 Dhuʿl-Qaʿdah 309 AH) on orders from Caliph al-Muqtadir. He was first severely flogged, then mutilated by having his hands and feet cut off, and finally decapitated. His body was burned and his ashes were thrown in the Tigris River under the supervision of Abbasid soldiers. Despite attempts to suppress his legacy, Al Hallaj’s execution only added to his prominence and he became widely revered after his death as a martyr of mystic love, especially amongst Sufi orders.

Endtail

While first-hand accounts of Mansur Al Hallaj’s time in Kashmir are scarce, later legends and links to local Sufi orders suggest his mystical journey left a lasting imprint on the region’s spiritual traditions. Kashmir’s openness to diverse faiths and philosophical inquiry around the ninth century would have proved conducive to Hallaj’s universalist message that transcended boundaries. The essence of his spiritual quest resonated through the centuries to inspire philosophers like Iqbal, and, countless others.