In Kashmir’s history, the invaders, despots and autocrats worked in close association with the feudal lords to control the land and the people, a situation that changed in 1947. Historian and author, Prof M Ashraf Wani found Prof Mushtaq A Kaw’s recent book ‘Kashmir Feudalism: Amid Changing Land Tenures’ refreshing as it discusses the rise and fall of Kashmir’s bourgeoisie

Right from early times we come across two Kashmirs – one belonging to a few rich, and the other to poor masses. Indeed, according to the European travellers, who visited Kashmir between 1586 and 1947, barring a handful of people, the Kashmiris were no better than beggars. Prof Mushtaq Kaw’s book, Kashmir Feudalism: Amid Changing Land Tenures provides a context to the heart-wrenching conditions of the toiling folk.

The book offers a background as to why my parents’ generation revered, to the extent of defying, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, the mass leader and the first Prime Minister of post-colonial Kashmir. Short of saying, the book also helps us to understand the reason d’etre the special steps taken by the post-1947 successive governments to uplift the fleeced peasantry generating social frictions with far-reaching consequences.

Influential Families

Several dynasties of different ideological hues and cultural backgrounds ruled Kashmir since early times resulting in significant changes in different spheres marking one phase off from the other. Yet, one fundamental factor namely production relations (if not forces of production) that determines and shapes the other spheres of life including the class character of the society, remained constant. Kashmir continued to be an agrarian economy characterised by a class of landlords and a class of subject and servile peasantry. It is on this substantive rather than semantic ground that Kaw wrote the book under the rubric Feudal Kashmir.

Kaw is pretty clear that feudalism in Kashmir was not a true copy of European or Indian feudalism. He, however, finds feudalism’s defining feature namely landlordism and fleeced peasantry central to the agrarian relations of Kashmir history.

During the pre-sultanate period, the revenue of the country was appropriated by two main agencies, namely the state and the landlords. The landed aristocracy was known by the blanket term, damaras, a pejorative term coined by Kalhana for the rebellious land-owning tribes. The land assigned by the state for secular or religious purposes created a landlord-dominated society, known by the generic term agrahara.

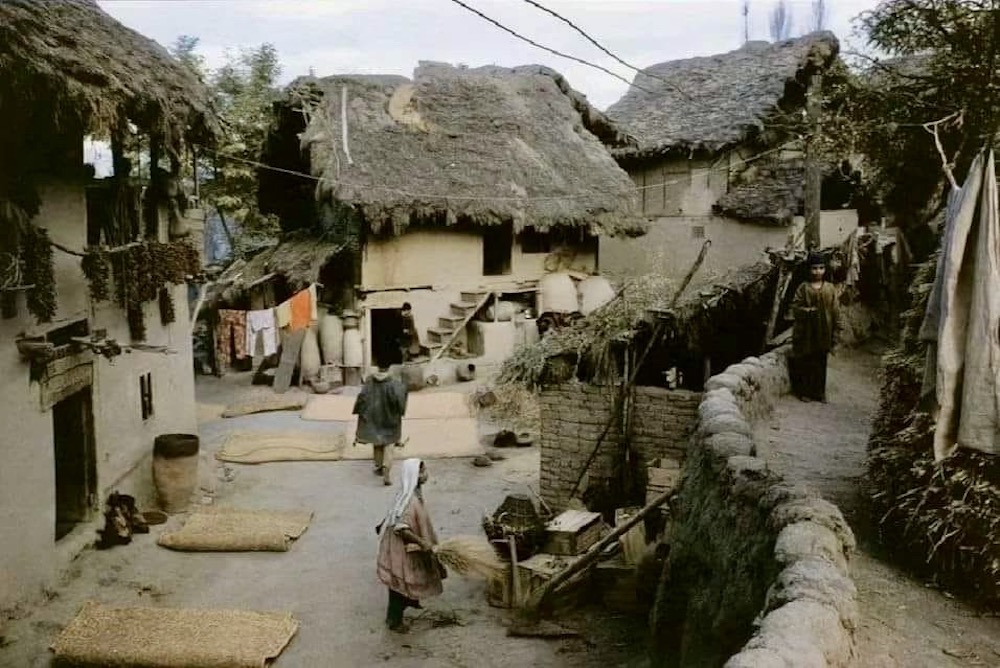

According to contemporary sources the state not only alienated land and other revenues to the assignees but they also transferred the people to them. The given production relations, thus, created a class-ridden society. The peasantry was not only subjected to rack renting but they were also inflicted illegal exactions and prerequisites. Thus, while on the one hand, we see Kashmir famous for its multi-storeyed houses owned by the rulers and landlords, we also come across the tattered houses with “the window formed by the mouth of a pot”. It is on the basis of these facts that Kaw considers the agrarian relations feudal in character.

Kaw does not elaborate on the agrarian relations during the sultanate period. By all accounts, landlordism continued during the Sultans; only the names and the composition of the recipients changed. Along with the Sultan, the landlords cum umara belonging to the dominant tribes namely Tantrays, Magrays, Lones, Dars, Nayaks, Chaks, Rainas, Thakurs, Baihaqi Sayyids, Bhats etc., ruled the roost. However, there was a relief in the overexploitation of the peasantry as the land revenue ranged between one-sixth and one-third. Moreover, like the pre-sultanate rulers, the sultans showed exemplary interest in excavating canals to the great benefit of the peasantry.

The Fall of Peasantry

The condition of the peasantry, however, worsened beyond precedent after the Mughal occupation and was exacerbated further during the succeeding Afghan, Sikh and Dogra regimes. Apart from imposing their ‘own’ jagirdars upon the local potentates reducing them to the position of zamindars, the Mughals increased the land and other revenues.

As if it was not enough the Mughal officials subjected the peasantry to such oppressive exactions that they were left with no other alternative but to desert the land. St Xavier who accompanied Akbar to Kashmir as his royal guest, laments over the forcible peasant flights owing to the violence committed on them by the Mughal Officers.

“It is a country which in olden times was provided with every kind of foodstuffs; now it is very much uncultivated and even depopulated from the time this king took it and governs it through captains who tyrannize over it and bleed the people by their extortions,” the visiting priest recorded. “Now everything is wanting for there are no cultivators on account of violence done them.”

Moorcroft, who visited Kashmir towards the beginning of the Sikh rule, saw the desertion of land by the oppressed peasantry having already assumed dangerous proportions.

“Everywhere, however, the people are in the most abject condition exorbitantly taxed by the Sikh government, and subjected to every kind of extortion and oppression by its own officers…,” Moorcroft recorded. “The consequences of this system are gradual depopulation of the country; not more than about one-sixth of the surface is in cultivation, and the inhabitants starving at home are driven in great numbers to the plains of Hindustan … The Village where we stopped was half deserted, and the few inhabitants that remained wore the semblance of extreme wretchedness; without some relief or change of system, it seems probable that this part of the country will soon be without inhabitants.”

The situation reached such a pass that according to GT Vinge the state imposed ban on leaving Kashmir without assigning “sufficient reasons.”

In Frying Pan

Kaw rightly argues that Kashmir was thrown from a frying pan into the fire after the British colonial power handed over Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh to Maharaja Gulab Singh. Immediately after assuming power, Gulab Singh revoked not only the proprietary rights but also the possession rights of the peasantry.

Worst, according to contemporary sources, even night soil was taxed; only air was free. Walter Lawrence has given a breathtaking detail of taxes and perquisites the peasants were subjected to. No wonder then, the eminent socialist, freedom fighter and historian, Prem Nath Bazaz laments over “the great misfortune of the Kashmiris that the British … did not take the Valley under their own control and instead handed it over to the medieval minded Dogras who “brought nothing but misery”.

The peasant was tied to the land. Nevertheless, the oppressed peasantry found ways and means to seek remedy in flight. The Kashmiri peasantry had assumed such a migratory character that ‘settling wanderers’ took a long time to Walter Lawrence.

“The work of settling the assamis of Kashmir was somewhat like that of placing men upon a chess board,” Lawrence wrote. “Not only had fugitives to the Punjab to be replaced in their villages, but men who had left their ancestral land for other villages had to be coaxed back.”

The Chakdars

Alongside breaking all records of the operation of the peasantry, the princely order promoted landlordism both vertically and horizontally. They not only maintained the existing jagirdari and maufi systems but they also created another category of landlords called chakdars.

As a result, there were about thirteen thousand landlords on the eve of 1947 who mainly belonged to the religion of the rulers as per medieval canons. To the great relief of the impoverished peasantry, the Jagirdari, chakdari and maufi systems was abolished by the popular government which took over in 1948. The land thus obtained was distributed among the tenants without compensation, thus bringing a revolutionary change in Kashmir. Kaw’s book contains a detailed discussion of these momentous developments.

Sultans to Sikhs

Interestingly, Kaw is unwilling to include the period from sultans to Sikhs (1339 -1846) within his framework of feudalism, because most of the land was under the proprietorship of the peasants during the period. I have a slightly different opinion on this point.

Firstly, as Kaw himself admits most of the land was held in ownership by the peasantry during the Hindu rajas too. Therefore, to dub one feudal and other non-feudal is difficult to fathom. Secondly, throughout the period covered by the book, Kashmir was dominated by the landed potentates called by different names.

During the period which Kaw considers non-feudal, the landed aristocracy carried the generic name jagirdars about which he has given details. Like the jagirdars of the Sultanate period onwards, the damras were basically landed magnates, owning large tracts of land and belonging to powerful tribes. It was by their powerful position that they were assigned different Vaisyas for purposes of administration and maintaining military contingents. They were not the owners of the land assigned to them. The same system continued during the subsequent periods.

Thirdly, in the given agrarian relations when the peasant was robbed off of his produce by the state and other agencies, ownership of the land had no material significance to the peasant, instead, it was a liability, a nuisance. He was not only fleeced by the oppressive state, but he was also subjected to beggar (forced labour). This is the reason that the peasants were least interested in cultivating the land.

Interestingly, according to Lawrence, the peasants were so stubbornly reluctant to cultivate the land that the tehsildar, who hardly moved out of his office, visited the villages during the sowing season to force the peasants to cultivate the land. It was only when the peasant became the owner of the produce of his land that land became an asset, a matter of life and death for the peasant. This was not even achieved by the abolition of landlordism. It was only with the abolition of mujwaza system by Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad that the peasantry felt the importance of being owners of the land.

Therefore, the real issue is the existence of superior right holders on the one hand and the over-exploited peasantry on the other – a fact that runs like a thread in the whole history of Kashmir. And as noted above from the sixteenth century onwards it assumed dangerous proportions. As a result, we see an impoverished peasantry, a depiction of which has been given by Kaw.

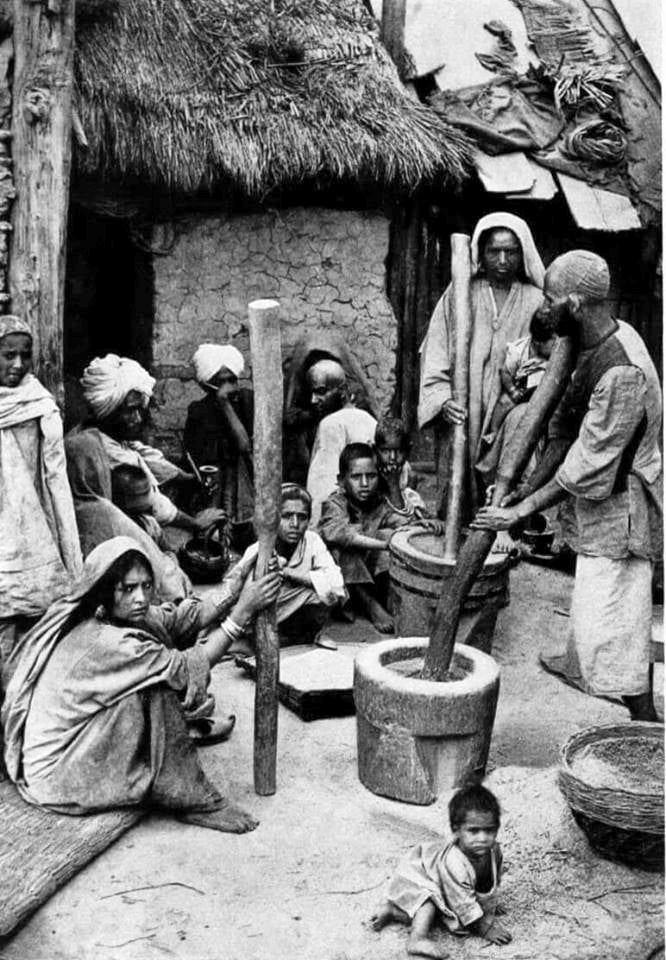

“The peasants’ extreme poverty was exhibited in their poor housing, dress, dietary and material and health conditions. Their material assets were few and simple, a wooden pestle a mortar for husking rice, a few earthen vessels for cooking and earthen jars for storing grains,” Kaw paints the grim picture of the peasantry. “Their houses were unhygienic mud-walled and thatched roofed, accommodating men, woman, children and animals together in closed door chambers. Usually, they had a single dress which until torn fully was not changed.”

Kaw leaves his readers wondering how the ‘feudalism’ of Kashmir was different from the feudalisms obtained elsewhere that prompted him to opt for the title Kashmir Feudalism.

Although a historian can claim the freedom to express his opinion, he is not free to sacrifice the facts. Kaw gives an opinion but he does not suppress the facts. This is the beauty of the book. Which is why it has the capacity to generate many meanings simultaneously. For those interested in knowing the agrarian relations that made up the social, economic and political structures of Kashmir over longue duree, Kaw’s Kashmir Feudalism is a rewarding read.

His inborn concern for critical societal issues surfaces towards the end of the book. Concluding the ‘post reform era’ Kaw strikes a note of warning about the risks involved in reckless land conversion, especially when Kashmir has been already reeling under land hunger. “The given crisis is likely to deepen for the massive existing and outlined Central Government projects in the Jammu and Kashmir for railways, roadways, highways, institution building, industrial set-ups etc., seeking therewith the dilution of the underlying purpose of land reforms in the formerly Jammu and Kashmir state or current Union Territory of India,” the book asserts.

(Former head of the history department at the University of Kashmir, Prof Ashraf has several books to his credit. His latest book The Making of Early Kashmir: Intercultural Networks and Identity Formation was published by Routledge in early 2023.)