by Tasavur Mushtaq

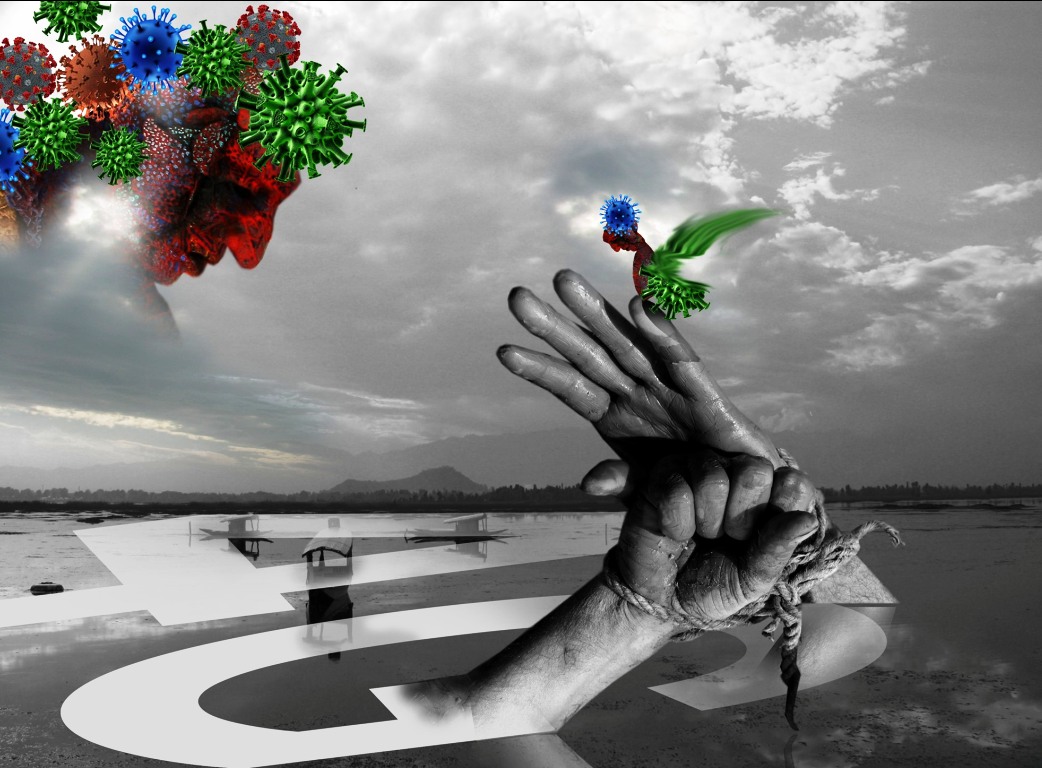

In January 2020, five months after Jammu and Kashmir was downgraded into two Union Territories, internet access was declared as a fundamental right. The declaration came from the apex court amid the continued ban on the internet in the UT.

As per the verdict, the three-judge bench said access to the internet is protected under Article 19 of the constitution. It affirmed that the right to freedom of speech and expression, as guaranteed to all citizens under the first section of that article, covers the right to go online.

Earlier the same court in 2017 while assuring everyone rights to life and liberty accorded privacy the status of a fundamental right under Article 21.

Four years ago, in 2016, the United Nations Human Rights Council upheld internet access as a human right. It made it clear that even barring online expression tantamount to the muzzling of the voice.

The Kashmir case, however, seems to be different. It has already got into the history books as a place with the longest internet shutdown in the world. As the 2G mobile internet was restored, the high-speed internet keeps on eluding. The seven million people continue to be deprived of accessing the virtual world at the desired speed.

On May 11, the case was listed before the three-bench judge. However, the concern did not see respite. The court agreed with the petitioners that the government was going against previously laid down principles, but rejected the restoration of 4G internet. There was no word on the violations of the judgment in Anuradha Bhasin vs Union of India by the government. Instead, the court abdicated its duty by constituting a “special committee” to review the restoration of the high-speed internet. Shockingly, the court asked the same executive to review the demand that ordered its ban.

It has been more than nine months since the day Kashmir last used high-speed mobile internet. A key necessity in the times of information age, the denial is daunting. In the last many years, a massive shift in approach has taken place. From classrooms to courtrooms, the advent of technology has been ingrained to the extent that it became a routine.

With this, there was an introduction of new domains in the valley. Professionals started their operations, young men and women had their share in technological innovations. The government also shifted various aspects of its procedures and systems to the online medium. The media too had to modify their resources from print to electronic platforms. Almost, everything was being managed digitally.

The shutdown, initially occasional and later permanently derailed the system from individual to the institutional level.

Currently fighting with the pandemic, the connectivity is a fundamental necessity. When in Kashmir, the government introduced digital tools to access and analyse various applications and customise with the changing scenarios, the only handicap emerged was the ban of government itself. The judiciary elsewhere is working through video conferencing, in this part of the world that too is facing difficulties.

With the call of physical distancing, the tough times required to have more virtual interactions, meetings and conversations.

Socially, the ban has barred people from interacting and seeing each other. Almost impossible to stream a video on low speed, the desire to see loved ones caught in lockdown stops at the blurred image only. With new websites designed for higher speeds, the dynamic nature doesn’t allow slow speed to let it operate smoothly.

The worst-hit education sector in Kashmir had a breather in February when schools were resumed. But soon after the virus took over, education took the back seat, again. As done worldwide, in Kashmir also online classes were started – an attempt to compensate for the loss of months. But given the speed, the students and teachers have a tough time. The live streaming for a class of 50 students is not possible. The results were dismal. As teachers try hard to teach, the students are lost in their won world. There is no sync. In between, the lessons flow and syllabus are said to be completed.

The ban has economic ramifications as well. A normal customer continues to pay for the 4G services and the applicable taxes, partly for 2G and partly for restrictions imposed on certain occasions. In the rest of India, a momentarily snag in services results in the mayhem, Kashmir screens has a message to display, “barred as per the directions of the government.”

Name a person in the political or social strata of Jammu and Kashmir who had not pleaded to restore the high-speed internet. Even the delegation went to meet the men in Delhi, but the pleas fell flat. Huge newsprint and digital space were consumed to seek restoration, but nothing materialized. No matter the level of request, the response is negative.

The sensitivity of the issue has not been sensed, yet. Hopeful of a respite, the court asked the executive to take a call. Interestingly, the constituted committee has members who are convinced to continue the ban.

The integration and involvement require understanding the issues from a wider perspective. Security prism may always take to a solution which is Us vs Them.