by Qysar ul Islam Shah

As copy-paste methods prevail, the art of handwriting is rapidly declining.

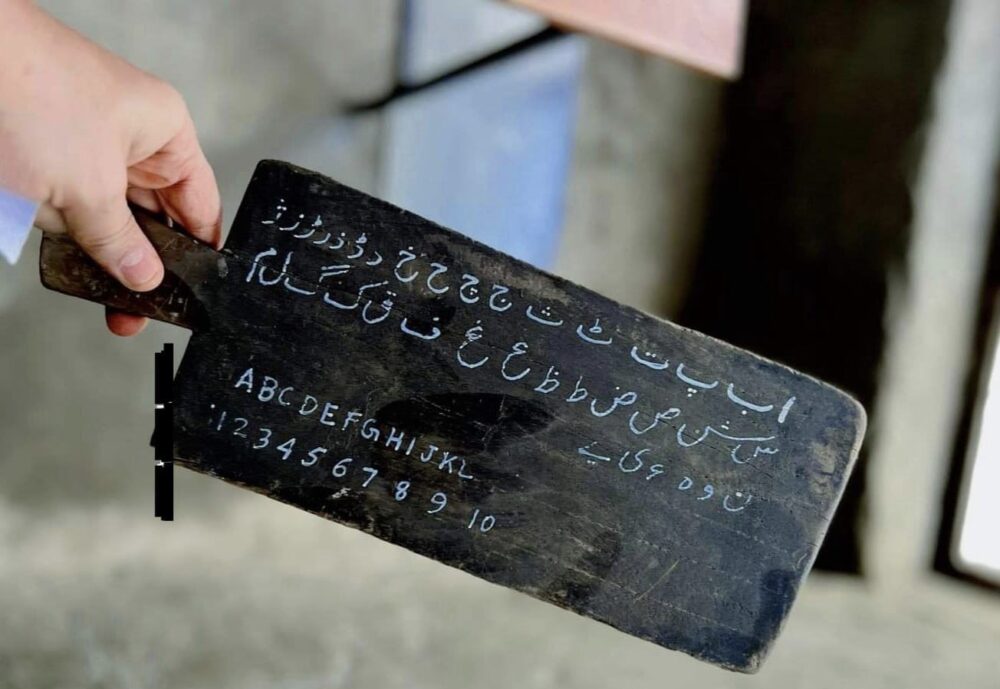

Mashq in schools, once a flourishing tradition, has encountered challenges and interruptions over the years. The traditional wooden slate, known as Mashq, was an essential tool for improving children’s learning and writing skills. It fostered eye-hand coordination and writing concentration, offering an economical and accessible option for every enrolled student.

During those times, schooling was characterised by a sense of wonder and joy. Mashq provided profound benefits, with teachers assessing writing quality and providing corrective feedback. Maintaining a clean and freshly written Mashq was imperative, with negative reinforcement for illegible handwriting.

Mashq is the Kashmiri term for Takhti or Wooden Slate. The practice of using Mashq can be traced back to the time of the Indus Valley civilization, suggesting an early familiarity with writing skills among its people. A Mashq resembles a wooden plank similar in size to a cutting board, often used by children in their initial years of schooling to write with a Narou Qalam or twig. In certain parts of Kashmir periphery, it was called Narkain Qalm. These were sourced from a local plant species that would look like a miniature bamboo. Mothers used to grow this plant in their vegetable gardens. Even the calligraphy students would use the same pens.

In schools, there existed a competitive atmosphere, with teachers offering appreciation and encouragement to those whose Masaq exhibited cleanliness both in writing and maintenance. This competition persisted beyond the morning assembly, with students gathering in groups to inspect each other’s Mashq before school hours.

Mashq served as an effective tool not only for improving students’ writing skills but also for mitigating the effects of dysgraphia, a neurological condition in which someone has difficulty turning their thoughts into written language for their age and ability to think, despite exposure to adequate instruction and education.

Reflecting on my own experience at the Government Middle School Darpora Lolab, now upgraded to a high school, I recall the ritual of arriving at school in groups, often an hour before classes commenced. There, alongside classmates, we meticulously examined each other’s Mashq, mindful of the teachers’ expectations. Even after school hours, the respect for authority remained palpable, with students refraining from crossing boundaries or engaging in play without permission.

I vividly recall the experience of attending the morning assembly, where certain teachers, such as Peer Abdur Rashid Shah, Ghulam Nabi Shah, and Ghulam Ahmad Kumar, among others, would inspect the lines, checking for cleanliness and proper attire. The mere anticipation of their scrutiny would send shivers down our spines, triggering perspiration, whether due to concerns about our uniform’s condition, the clarity of our prayers, or the legibility of our Mashq.

Following the assembly, announcements were made regarding absentees from the previous day, requiring them to account for their absence. This process instilled a sense of apprehension, as students feared being singled out and placed in a row of guilt, subject to physical punishment in the form of lashes with a long, hard twig.

Once the checking process concluded, students were directed to return to their respective classrooms. Meanwhile, we were tasked with cleaning and preparing our Mashqs for the following day, a laborious process involving the application of a cotton cloth soaked in a mixture of black soot and water, followed by sun-drying and polishing with bottle bottoms or cup brims (Mohar Deun). Despite the effort involved, there was a sense of camaraderie and competition among us during those times.

Reflecting on our school days, the presence of a Mashq in hand was an unspoken rule, universally adhered to. Despite its affordability, even the most economically disadvantaged students could readily acquire one. Durable, manageable, and user-friendly, the Mashq not only facilitated writing but also aided in expanding vocabulary. Writing pencils, such as the Naroue Qalam, were sharpened with a knife and dipped in ink, allowing for the transfer of thoughts onto the Mashq.

Regrettably, the tradition of the Mashaq is gradually fading from Kashmir, becoming a rarity.

The Mashq faded from schools gradually. Around the 1980s, these were replaced by Rogan Mashq, which did not require a lot of pre-writing preparation. It had painted lines already. Then it paved the way for pencil and copy which soon was replaced by ballpoint pens. In the last decade cell phones and computers pushed the new generation in the new direction.

Presenting this tradition to the current generation often elicits disbelief, as the proliferation of technology and modern writing tools has supplanted the age-old practice of handwriting. The Mashq was instrumental in helping school kids improve their handwriting. Some of them would become calligraphers without any formal training. Now as copy-paste methods prevail, the art of handwriting is rapidly declining. We must endeavour to revive this tradition.

(The author is a teacher from Sonnar, Darpora. Ideas are personal.)