by MJ Aslam

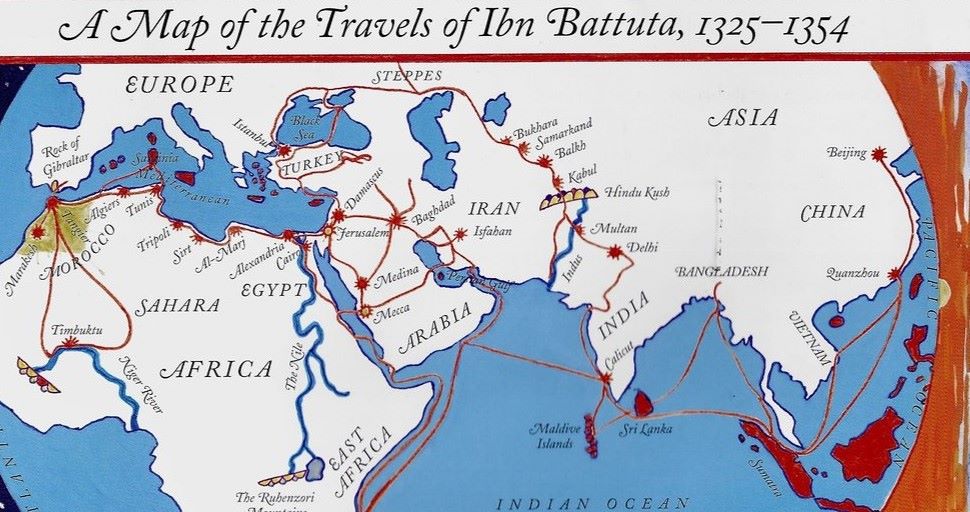

Celebrated North African Arab Traveller, Ibn Battutah covered almost 75000 miles in 29 years across continents to write a credible fourteenth-century travelogue. It offers interesting details of how different societies and countries observed the Muslim month of fasting

Ramadan, the annual fasting by Muslims is one of the five fundamentals of Islam. It begins annually with the sighting of the new moon on the 29th day of Shaban, the ninth month of the Muslim lunar colander. How Ramadan and Eid ul Fitr were observed in medieval times by Muslims the world over?

For the answer, there does not seem to be any other person than fourteenth-century North African Arab traveller and Faqih (jurisprudent), Sheikh Abu Abdullah Mohammad, fondly known as Ibn Battutah, more accurate in guiding our walk through the several Muslim societies of his time in his travelogue, the Rehla.

After thirty years of travel of several countries which started in June 1325, covering 75,000 miles of North West Africa, Egypt, Syria, Makkah and Madina, Southern Persia and Iraq, Southern Arabia, East Africa, and the Arabian Gulf, Asia Minor, Steppe, and the Constantinople, Turkistan and Afghanistan, North and South India, Maldives, Sri Lanka and Coromandel Coast, Bengal, Assam, South East Asia, China to Morocco, then Spain and Indonesia, and finally he reached back to Morocco in 1354. His accounts were written down by a younger writer, Ibn Juzay, under the orders of the Moroccan king, Sultan Abu Inan.

The rich religious and cultural traditions narrated by this greatest traveller of the medieval world are universal among Muslim communities’ world over to date. In the absence of modern communication outlets, how the sighting of the crescent was communicated by the Muftis, Qazis, and how the holy month of Ramadan and Eid were observed and celebrated in the medieval period of Islam are worth knowing.

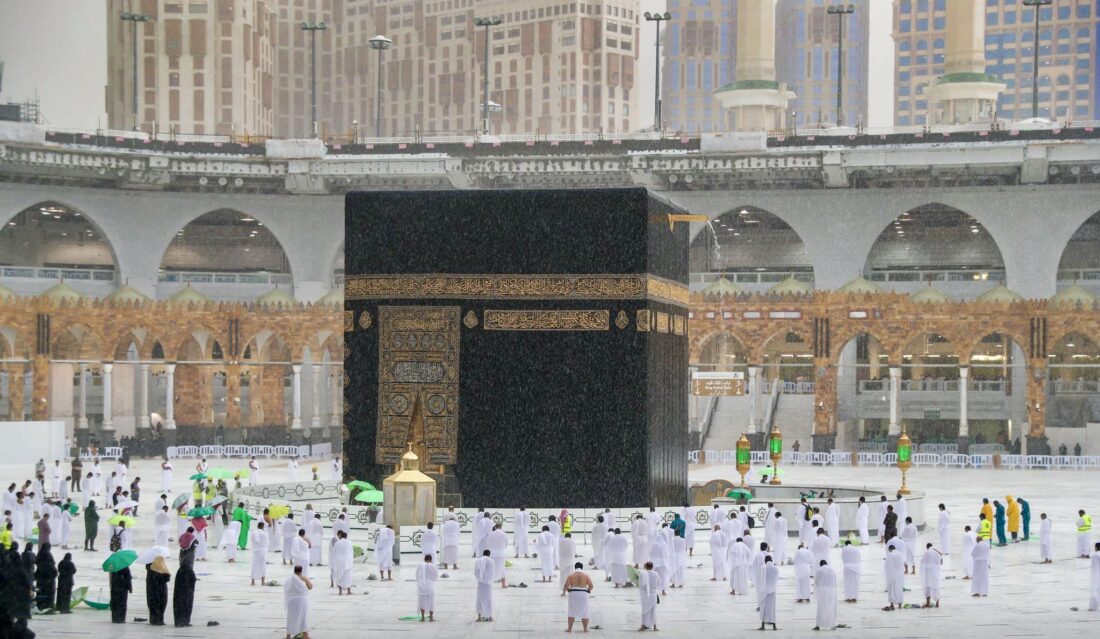

The Land of Kaaba

In 1325, he visited the Holy Kaaba and the Masjid-e-Nabvi in Madina. He found the Muslims of Makkah and from distant places assembled to prepare themselves for the approaching Ramadan right from the middle of Shabhan.

On the appearance of the new moon of Ramadan, “the drums and kettle drums were beaten at the house of the Amir of Makkah, and great preparation was made in the Sacred Masjid by way of renewing the mats, augmenting the number of candles and torches until the Sanctuary gleams with light and glows, radiant and resplendent”.

The Mu’zin gives Adhan, the call for prayers, and “the Imams form separate groups (each with the followers of his rite), that is to say, the Shahfis, Hanafis, Hanbalis, and Zaidis” recited the Qur’an in turns and the light candles were placed in front of each Imam. They performed special prayers, Tarawih. There was not a corner or spot left in the Sanctuary but it was occupied by some Quran-reciter leading a group in prayer, so that the mosque was “filled with a babel of readers’ voices, and all spirits are softened, all hearts wrung, and all eyes bathed in tears.”

When the time came for taking the last meal (Sahar) before daybreak, the Mu’zin of Zamzum from the eastern angle of Kaaba gave the Adhan as he had “the duty of announcing Sahar (time to take meals) from the minaret by summoning, reminding, and urging all people to make their early repast, followed by the muezzins on the remaining minarets.” On the top of each of the four minarets, a crosspiece was erected at its head on which were suspended two great glass lanterns “kept alight (during the hour of the Sahar), and when the hour of dawn approached, the warning to cease from eating” was “issued time after time, the two lanterns were lowered, and the muezzins begin the call to prayer, responding one to the other”. The “great glass lanterns” were kept for those who could not hear the Adhan given for ending Sahar.

On every odd night of the last ten days of Ramadan, the Imams “seal the Quran”, that is, recite the whole of the Quran (Khatm e Quran]. On the appearance of the Shawal moon, the lamps were lit on all minarets, from top to bottom, and the illustrious Sanctuary was illuminated with lights from all sides. The scholars, Qazi and notables, present in the Kaaba, were invited by the Amir of Maaka, “to his house, where he entertained them with a great variety of viands and sweetmeats” on each of the odd nights of the last ten days of Ramadan when the Holy Quran was sealed by the Imams.

On the appearance of the Shawal moon, the people would make preparations for the Eid celebration on the first Shawal. After saying dawn prayers (Fajar) in Kaaba, the people dressed themselves in “finest clothes”. They arrived in the Holy Sanctuary in a soulful atmosphere of aroma to offer congregational festival prayers [Eid Nimaz]. These practices continued each year.

In Egypt

In 1326 CE, Ibn Battuta was at Abyar (Egypt). On the 29th of Shabhan, the Islamic scholars and notables, all wearing turbans and in fine clothes assembled after the sunset prayers at the house of the Qazi of the town. A Naqib stood at the door of the Qazi’s house. He welcomed and guided the incoming guests to take their seats in the hall of the Qazi’s house.

The Qazi and the guests then rode off in a procession, followed by men, women and children of the town, and made their way to a place of eminence outside the town, well furnished with rugs and carpets, which was called by them Observatory of the Crescent Moon, something resembling the now-established Ruet e Hilal Committees. The Qadi and other scholars alighted from their horses and camels to observe the new moon. The Cavalcade was prominent by candles, torches and folding lanterns.

After observing the moon, the people returned to the town and accompanied the Qazi up to his house. The shopkeepers kept lighted candles. This practice of sighting the crescent was done each year by the residents of the town, records Ibn Battuta.

In Turkey

In 1331, Ibn Battuta was in the city of Akridur (Egirdir in modern Turkey) and during the month of Ramdhan, Abu Ishaq Bak, the sultan, invited Islamic scholars and notables for fast breaking (Iftar] to his palace where he preferred to sit on the carpet spread over the floor, instead of on a royal couch, and would listen to the soulful recitation of the Quran from the reciters. Then, the food was brought in and the first dish with which the fast was broken was tharid (Arab cuisine of bread-coup), which was served on a small platter and topped with lentils soaked in butter and sugar. Taking Tharid has been the blessed tradition of the Holy Prophet [PBUH].

After Tharid, other dishes were brought in and this was done on all nights of Ramadan. The Amir of another city Denizli of modern Turkey too was generous with scholars and his subjects. On Eid day, Ibn Battuta recounts, the Sultan came to pray in the Musaala. It may be noticed here that for the two annual festival prayers, which the entire population was expected to attend in all Muslim societies, the ordinary mosques were too small, and it was customary then to hold them on a special plot of ground, called the Musala, usually outside the walls of the masjids.

Musala is the praying ground where Muslims assemble on the days of two annual festivals Eid ul Fitir and Eid ul Adha for Eid congregational prayers. In the Indian subcontinent, it is known as Eid Gah, usually outside the city, while the word Mussala refers to a small prayer mat used by each worshipper. Attending Eid prayers at Eidgah is the Prophetic Sunnah.

The groups of people carrying flags, and drums, and chanting Kalimat, arrived at the Mussala for prayers. The meat and other foodstuffs were distributed among the people. Then, at Amir’s residence, the guests, scholars, rich and poor were served a feast of fast-breaking. No one was turned back from the door of the Amir.

Uzbik Sultans during Ramadan served the guests cooked goat’s meat, rishta, which is a kind of macaroni cooked and supped with milk.

In 1332, Ibn Battuta was in the city of Bulghar (an ancient city of modern Volga Bulgaria) where he had the Tarawih prayer of Ramadan.

In Tunis

Ibn Battuta was in Buna town (where Caserne Saussier was built later in 1835) of Tunis in 1325 where he encountered an incident exactly which the teacher of his contemporary, Ibn Juzay, has met at Ballash (Velez) city of Andalus, modern countries of Spain and Portugal, which were ruled by Muslims then.

Ibn Juzay narrated to him that his teacher had gone to the festival praying ground with all the people of Ballash, and when the prayer and allocution were finished, they all began to exchange greetings with one another, while he remained apart, without anyone to say a word of greeting to me. Then an old man, one of the inhabitants of this town, made towards him and came up to him with a greeting and friendly welcome saying: “I looked at you and saw that you were standing apart from all the others, with no one to greet you, so I knew that you were a stranger, and thought I would say a friendly word to you”.

It was among the rich traditions of Muslims to greet each other daily in all societies and the fervour was doubled of festivities. The strangers too were greeted with friendly words. Abu Yahaya (1311-1346) was Sultan of Tunis when Ibn Battuta arrived there. While he was still in Tunis, he was overtaken by the feast of the Eid festival.

Sultan Abu Yahaya arrived in a magnificent caravan with his courtiers at the Mussala where the inhabitants of the city in large numbers had already assembled in their richest apparels to celebrate the festival. He too joined the company at the Musalla. The prayers were said and allocution (Khutba) was discharged. The people greeted each other before returning to their residences. It is a universal custom among Muslims to celebrate Eid festivals with great animation and gaiety and put on new clothes for the occasion.

In Syria

In July 1326, he left Cairo (Egypt) for Syria and after travelling through historic cities of Syria including Ghazza and Aleppo, he was in Damascus in the holy month of Ramadan in August 1326. In his own words: “It is one of the laudable customs of the people of Damascus that not a man of them breaks his fast during the nights of Ramadan entirely alone. Those of the standing of amirs, qadls and notables invite their friends and (several) faqirs to breakfast at their houses. Merchants and substantial traders follow the same practice; the poor and the country folk (Bedouins) for their part assemble each night in the house of one of their number or a mosque, each brings what he has, and they all breakfast together”.

Ibn Battuta was taken to his own house by a renowned Maliki scholar, Nur ud Din, for Sahur during Ramadan telling him “consider my house as your own, or as the house of your father or brother”. Ibn Battuta fell ill during Ramadan and Nur ud Din attended to him and brought a doctor for his treatment and he celebrated Eid ul Fitir at his residence. He attended Mussala of Damascus which was built in 1318 by Saif ud Din, brother of Salah ud Din Ayubi.

In India

Ibn Battuta was in India for six years from 1333 and acted as Chief Qadi in the court of Mohammad Bin Tugluq. He recorded that there were tanks, and water reservoirs, built by Sultan Altumush (d 1236), in Mehrauli which were used by inhabitants for drinking water and near to the tanks was Mussala. There is a famous tomb of saint, Qutub ud Din Bakhtiyar Kaki, the disciple of saint, Mohi ud Din Chisti, in Mehrauli. There lived also musicians around this area which was called Tarab Abad.

During Ramadan, he witnessed great enthusiasm among the people including the musicians to attend Tarawih prayer after Imam in the Mussala. Each one of the musicians, he saw, “had a prayer mat under his knees, and on hearing the Adhan rose, made his ablutions and performed the prayer”.

On the occasion of Eid, it was practice on the part of the Sultan to send robes of honour to Maliks, courtiers, officers of the State, foreign dignitaries called Aziz, naqibs, muzins, qadis, slaves, couriers and all the elephants of royalty were adorned with silk, gold, silver, jewels and precious stones. While marching towards Mussala for Eid prayers, the slaves and the Naqibs walked on foot in front of the Sultan, with flags, drums, trumpets, bugles and pipes, and they wore fine outfits, caps and girdles adorned with gold. The use of drums, trumpets, bugles and pipes was an adaptation of the Hindu Rajas cultural tradition by Sultans of Delhi.

All devotees including Muzins while marching to Mussala recited Allah u Akbar, Allah u Akbar, in a soulful rhythmic tone. A marquee of cotton was spread over the Mussala which was decorated with carpets. The Imam would then lead the Eid prayers and deliver the Khutba in the Mussala, which was attended by the Sultan and scholars and notables too.

After Eid prayers, the inhabitants returned to their homes and a great feast was served to nobles in an audience hall of a large tent, called Barka, by the Sultan and the palace and pavilions were well decorated in multiple colours.

Ibn Battuta has recorded that on Eid festivals, he prepared “a hundred mounds” of food for the poor. At Dawlat Abad (in present-day Maharashtra) which was the temporary capital of Delhi Sultans, Ibn Battuta records, there were mosques as in Delhi where Imam held Tarawih prayers during Ramadan.

At Kolam (Kerala), the Muslims recited the Quran in masjids during Ramadan and attended congregational prayers on Eid in Mussala.

In 1334 at Maldives, Ibn Battuta witnessed the same religious zeal among the Sultan and Muslims during Ramadan. From Cairo (Egypt) to Turkistan, Mali (Indonesia), Sind to Hind, the custom of observing the fast of Ramadan and celebration of Eid festivals was uniform with the same religious fervour. On these special occasions of Ramadan and Eids, the Sultans, all over the Muslim world fed the people of their countries, clothed and fed, and he noticed that the Sultan of Mali distributed Zakat on the 27th of Ramadan (Shabi Qadar] to the Qadis, scholars and Fuqha, poor and destitute, says Ibn Battutah. According to Ibn Khaldun, the Muftis, like other Muslim scholars of Islam, were not generally wealthy.

A mention of dates

Breaking the Ramadan fast with dates is an Islamic Tradition. Phoenix dactylifera or date palm tree does not grow in Kashmir. The fruit of the date palm, Kha’ir, is, without exception, used by all Muslims the world over in Ramadan. There does not seem to be evidence that Kashmiri Muslims were used to the breaking of the Ramadan fast, at Iftar with dates.

The dates were and are cultivated in Makran coast, Baluchistan, Punjab’s Multan, Dera Ismail Khan of KPK, Muzzzafargarh and Sind of Pakistan. Before partition, these dates were exported to Leh where they were largely transported to Yarqand and Lhasa Tibbet. A small quantity of the dried dates from the United Punjab would also find its way into Kashmir in the late 19th century. The best of the dates always were cultivated in the Arabian peninsula, Basrah, Bahrain, and Oman, and on record, large quantities of dates were imported to India from Oman in the past. North Africa and the Sahara were and are also famed for the cultivation of date palms.

The significance of dates in Islam and Muslim cultures can be gauged from the fact that there is a reference to dates in 20 places in the Holy Quran. Under the Sunnah of the Holy Prophet (PBUH), it is far better to do Iftar with dates. “When one of you is fasting, he should break his fast with dates; but if he cannot get any, then (he should break his fast) with water, for water is purifying” (Hadith).

Iterating, the dates though were imported to Kashmir in the past from the United Punjab before partition, there is not much evidence that it was a practice among the Kashmiri Muslims to break their fast with dates in Ramadan. As the awareness about Islamic Traditions, trade with the outside world and travel to Muslim countries especially Makkah and Madina of Saudi Arabia for Hajj and Umrah, progressed and increased in the valley over the past decades, the Islamic tradition of breaking fast with dates became a permanent feature of the Dastarkhan at Iftiyari in Muslim homes and masjids of Kashmir.

Countless varieties of dried and fresh dates in beautiful packages and even in the open, with varying costs depending on the quality, now readily available everywhere, are decorating all the known bazaars of Kashmir during the Holy month of Ramadan.

There is great significance of dates in the Holy Scriptures of all Abrahamic religions of Islam, Judaism and Christianity.

(MJ Aslam is a historian and author.)