by

With forecast reductions in rainfall predicted to decimate the gross domestic product (GDP) of Middle Eastern countries, climate change represents a critical threat to these countries

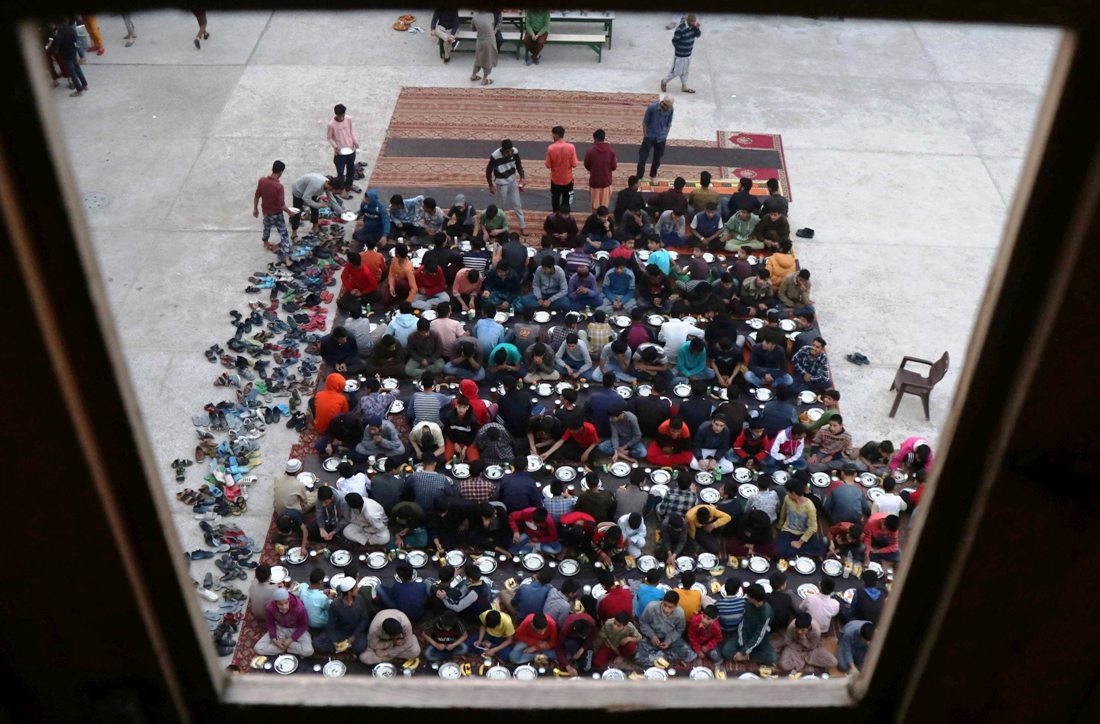

Every Ramadan, volunteers at Westall Mosque and OneSpace in Melbourne hold free weekly iftars (communal dinners to break the fast in Ramadan). This year, volunteers say numbers are up.

To cut down on the resulting landfill, attendees are asked to bring their own reusable food containers and water bottles. In dedicated bins, bottles and cans are collected and recycled under the state government’s container deposit scheme – adding A$12 to A$25 every weekend to each mosque’s coffers, volunteers say.

Many of the attendees are international students from Indonesia or Malaysia. Living away from their families, paying high tuition fees, and juggling precarious work with studies, they represent a segment of Australian society particularly hard hit by rising costs of living. These include a jump in food prices stemming from global warming-induced crop failures.

This is a small example of a global problem. The way Muslims around the world experience Ramadan is changing because of climate change, often for the worse.

Food insecurity all year round

Like members of Australia’s other Islamic communities, Melbourne Muslims of Indonesian background make up a privileged minority, living in a prosperous, peaceful country.

Muslims in other parts of the world face exacerbated challenges.

Several of the countries thought to be the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change are countries with Muslim-majority populations (such as Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Pakistan).

In the Middle East and North Africa where Muslim-majority countries abound, the World Food Programme describes a “persistent food security crisis”.

In this region devastated by conflict and climate change, the World Food Programme says the practice of abstaining from food (temporarily, as a religious tradition) has become an ongoing reality for millions throughout the year.

Food insecurity is made worse in the Middle East and North Africa by the aridity of the region, which contains 12 of the world’s driest countries. These include Algeria, Bahrain, Qatar, the Palestinian Territories, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and Yemen.

With forecast reductions in rainfall predicted to decimate the gross domestic product (GDP) of Middle Eastern countries, climate change represents a critical threat to these countries.

Extreme weather driving extreme losses

Food insecurity and water scarcity aren’t the only ways in which the effects of climate change are felt in Ramadan.

Increasing temperatures have led to the forcible displacement of communities from extreme weather incidents such as storms, wildfires and flooding.

In 2022, flooding in Pakistan destroyed water systems and forced more than five million people to rely on ponds and wells. This contributed to a rise in disease as this water was contaminated.

Heat waves during times of fasting can also prove fatal. In 2018, dozens of people died in Pakistan, amid sweltering temperatures at the start of Ramadan.

After an extreme weather incident, a conflict-afflicted country will shoulder four times the hit to its gross domestic product, compared to a stable country.

Permanent GDP losses of 5.5 per cent have been recorded in Central Asia and just over 1 per cent in the Middle East and North Africa, following climate disasters.

Such losses compound the already precarious stability of these Muslim-majority countries.

Over time, extreme weather events such as flooding in Bangladesh impact the production of necessities.

At a practical level, the loss of income that results when entire towns are swept away affects local economies during Ramadan and beyond, as survivors spend less, and opt for more frugal celebrations.

‘Greening’ Ramadan

Wealthier countries, in general, are better equipped to mitigate climate change impacts.

But in Muslim-majority countries in the global south, there has been a push for “greening” Ramadan, and for environmentally sustainable practices to be incorporated into daily Muslim life.

Mosques like Masjid Salman on an Indonesian university campus have incorporated tissue-less and water-efficient areas for wudhu (the ritual ablutions before prayer).

Solar panels installed in 2019 power the largest mosque in southeast Asia – Jakarta’s Istiqlal Mosque. Its capacity matches that of the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

The belief that caring for the environment is an aspect of the Islamic faith holds true for people like Indri Razak, a resident of Sumatra’s largest town of Pekanbaru and a member of the environmental group SRI Foundation.

She’s tried to implement a plastic-free lifestyle in a country where sustainability is just beginning to be embraced.

“As Indonesians whose population is in the hundreds of millions, we need to start taking measures in reducing food waste,” she says.

“I hate composting – it’s so much easier to chuck it all in the bin and off it gets collected by the garbage truck, but if I can do it, anyone can.”

In the meantime, a 1,400-year-old fasting tradition continues in a world with a changing climate. Despite centuries of Ramadan, Muslims now practice their faith amid very modern environmental challenges.

(The author is a senior Lecturer, at the Department of Media and Communication, La Trobe University. Born in Jakarta and raised in Melbourne, Dr Nasya Bahfen is a former journalist, now an academic, who has worked in Australia, Singapore and New York. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.)