by Muhammad Nadeem

The Red Heifer narrative highlights how religious beliefs can shape political landscapes and ignite conflicts. Central to this narrative is the pursuit of purity and perfection, exemplified by the rigorous criteria for the red heifer. This theme extends beyond religious contexts, resonating in broader societal and political spheres where the pursuit of purity often leads to extremism and division.

The saga of the Red Heifer traverses’ millennia, weaving the faiths of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism into an intricate fabric of belief, ritual, and prophetic interpretation. Central to this narrative is a modest bovine, elevated to profound symbolic status by sacred texts that underpin the spiritual and cultural foundations of the Abrahamic traditions. Untangling the historical strands binding the Red Heifer to the volatile junction of Palestine, Gaza, and Israel—where ancient prophecies intersect with contemporary geopolitical turmoil—demands a thorough examination of religious doctrines, archaeological findings, and the intricacies of regional conflicts.

The Sulaimani Temple

Understanding the significance of the Red Heifer requires a look into the foundational texts of religious revelation. Jews are the Bani Israel of the Quran. They are the descendants of the prophet Hazrat Yaqoob, who was known as Israel. Prophet Dawood began the construction of the temple, Muslims know it as Haikal, but he was unable to finish it during his reign. It was later completed during the era of Suleman, the prophet who had control over Djinns and would understand the language of birds, animals and insects. That is why it is known to Muslims as Haikal E Sulemani.

Following the Babylonian destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE, the Jews of the Kingdom of Judea were exiled. It was not until 538 BCE, under the rule of Cyrus the Great, that they returned to Jerusalem and reconstructed the Second Temple on the original site. However, in 70 CE, Jerusalem fell to the Romans, destroying the Second Temple, and leaving only a section of the western wall intact (though recent archaeological findings suggest parts of the wall date to later periods). The Western Wall continues to hold immense sacred significance for Jews.

Reconstructing the Temple, for the third time has remained a historic movement within the Jewish population. The Jewish Talmud delineates the prerequisites for the advent of the Messiah. Jewish historians believe that red heifer sacrifices have been made nine times in Jewish history and a repeat of the sacrifices for the tenth time will result in the advent of the all-powerful Messiah. One such condition involves the reconstruction of the Temple, specifically on the site of the ancient Sulaimani Temple, referred to as the Third Temple.

The Red Heifer

According to Jewish tradition, this entails the removal of the Al-Aqsa Mosque. For this purpose, a red heifer must be sacrificed, and its ashes utilised for purification:

The Lord said to Moses and Aaron: “This is a requirement of the law that the Lord has commanded: Tell the Israelites to bring you a red heifer without defect or blemish and that has never been under a yoke. Give it to Eleazar the priest; it is to be taken outside the camp and slaughtered in his presence. Then Eleazar the priest is to take some of its blood on his finger and sprinkle it seven times toward the front of the tent of meeting. While he watches, the heifer is to be burned—its hide, flesh, blood and intestines.

The priest is to take some cedar wood, hyssop and scarlet wool and throw them onto the burning heifer. After that, the priest must wash his clothes and bathe himself with water. He may then come into the camp, but he will be ceremonially unclean till evening. The man who burns it must also wash his clothes and bathe with water, and he too will be unclean till evening.

“A clean man shall gather up the ashes of the heifer and put them in a ceremonially clean place outside the camp. They are to be kept by the Israelite community for use in the water of cleansing; it is for purification from sin. The man who gathers up the ashes of the heifer must also wash his clothes, and he too will be unclean till evening. This will be a lasting ordinance both for the Israelites and for the foreigners residing among them. (Numbers 19:1-10)

“The ashes of a heifer sprinkled on those who are ceremonially unclean sanctify them so that they are outwardly clean. How much more, then, will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself unblemished to God, cleanse our consciences from acts that lead to death, so that we may serve the living God!” (Hebrews 9:13–14)

In Jerusalem’s sacred geography, Jewish traditions echo the biblical saga of the Temples’ rise and fall, coupled with the fervent aspiration for a Third Temple’s revival. The Red Heifer assumes a pivotal role, its sacrificial ashes are deemed a purifying necessity for the construction of this prophesied structure.

The Quran Says

Similarly, Islam acknowledges the importance of the bovine, with the Holy Qur’an recounting:

And (remember) when Musa (Moses) said to his people: “Verily, Allah commands you that you slaughter a cow.” They said, “Do you make fun of us?” He said, “I take Allah’s Refuge from being among Al-Jahilun (the ignorant).” They said, “Call upon your Lord for us that He may make plain to us what it is!” He said, “He says: ‘Verily, it is a cow neither too old nor too young, but (it is) between the two conditions’, so do what you are commanded, ” They said, “Call upon your Lord for us to make plain to us its colour.” He said, “He says: ‘It is a yellow cow, bright in its colour, pleasing the beholders.”

They said, “Call upon your Lord for us to make plain to us what it is. Verily, to us all cows are alike. And surely, if Allah wills, we will be guided.” He [Musa (Moses)] said, “He says: ‘It is a cow neither trained to tilt the soil nor water the fields, sound, having no other colour except bright yellow. ‘ “They said, “Now you have brought the truth.” So they slaughtered it though they were near to not doing it. And (remember) when you killed a man and fell into dispute among yourselves as to the crime. But brought forth that which you were hiding. So We said: “Strike him (the dead man) with a piece of it (the cow).” Thus Allah brings the dead to life and shows you His Aya: (proofs, evidence, verses, lessons, signs, revelations, etc.) so that you may understand. (Al-Baqarah, 67-73)

The Qur’an highlights the symbolic significance of specific cow types and their ritualistic role, echoing the Jewish tradition’s reverence for the Red Heifer. Despite differing contexts, a mutual veneration for the bovine emerges across the Abrahamic faiths. This need to be mentioned that the Quranic discourse of the bani Israel has a heifer highlighted because these people constructed a golden heifer in the absence of Moses and started praying to him.

The Twenty-first Century

As the narrative transitions to the present, the Red Heifer becomes a focal point in the volatile Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Procured at considerable expense from Texas to the occupied territories, these rare specimens signify certain groups’ determination to fulfil the prophetic conditions surrounding the Red Heifer. Leading this effort is the Temple Institute, a right-wing Israeli organisation, heightening tensions, and sparking concerns over the potential consequences of such a sacrifice.

At the heart of the dispute lies the belief that constructing the Third Temple necessitates demolishing the Al-Aqsa Mosque, one of Islam’s revered sites. This belief, rooted in particular interpretations of Jewish scripture and tradition, directly contradicts Islamic principles and the historical significance of the mosque. The prospect of desecrating this sacred site has triggered widespread condemnation and fears of escalating violence in an already unstable region.

Engineered Prophecy

The narrative unfolds to explore the broader philosophical and theological foundations shaping discussions on the Red Heifer and its ‘prophetic’ implications. Certain Zionist Christian and Jewish factions embrace an ideology suggesting that human actions can actively fulfil prophetic narratives, hastening the arrival of the end times.

In navigating the ‘End of Time’, the flaws in this approach and the dangers of misinterpreting religious texts to justify apocalyptic agendas are immense. The cautionary tale of figures from the past, who anticipated the fulfilment of prophecies through the arrival of an army from Syria, serves as a warning against such distorted ideologies.

Political figures garner support from Christian and Jewish Zionists who share similar beliefs about ushering in the end times. However, their actions, such as the oppression of Palestinians, contradict the teachings of their respective faiths.

This contrast highlights the inherent contradiction between the pursuit of apocalyptic narratives and the ethical principles that underpin the Abrahamic faiths—principles advocating for justice, compassion, and respect for human dignity.

Faith Identity Symbiosis

The descendants of Ismael share ancestral ties to the events unfolding in Palestine today. Their narrative is one of courage, resilience, and independence amidst adversity.

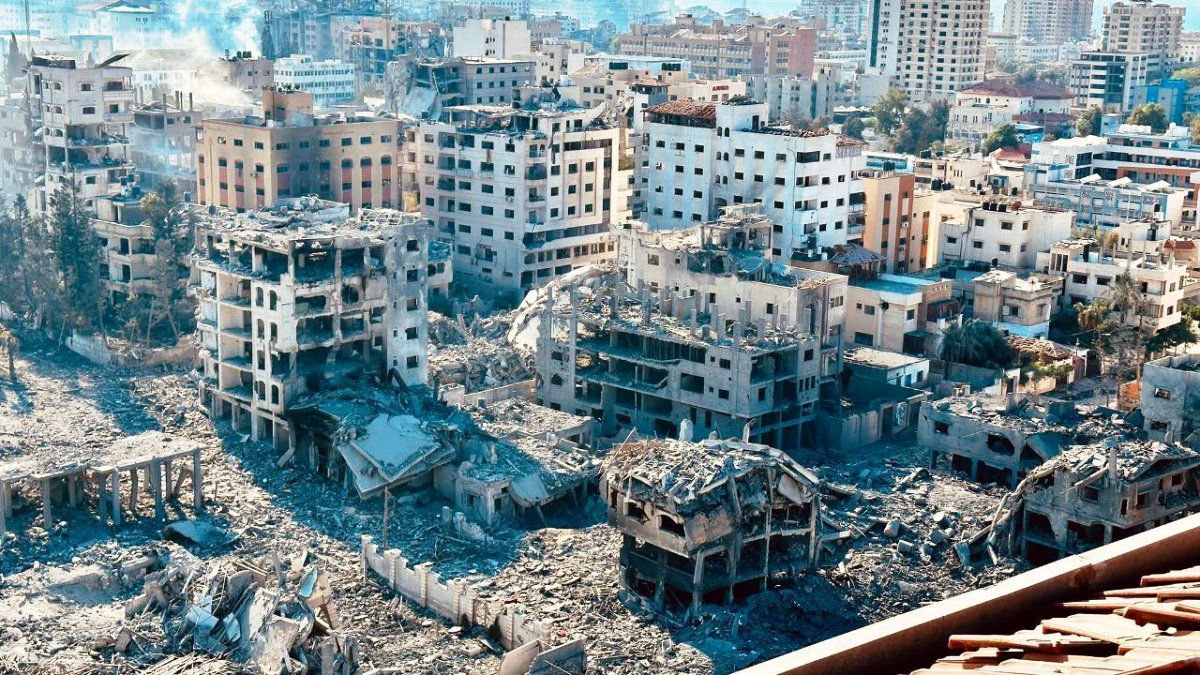

Palestine is juxtaposed with the perseverance and resolve of the Palestinian populace, who have faced significant challenges in their quest for self-determination.

The misuse of the term ‘anti-Semitic’ to condemn Palestinians who oppose the occupation is deeply troubling. Islam’s historical protection of Jews during periods of persecution contradicts the tendency to equate legitimate criticism of Israeli policies with anti-Semitism. Moreover, Palestinians, as Semitic people, possess a profound connection to the land, and historical examples of peaceful coexistence between Muslims and Jews often get overlooked in the conflict’s polarising discourse.

The Role of Narrative

The saga of the Red Heifer intertwines the ancient traditions of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism with the complex history and contemporary realities of Palestine, Gaza, and Israel. It transcends religious allegory to symbolise the intricate dynamics shaping the region’s geopolitical landscape.

At its core is the belief in the purifying power of the ashes of a perfectly red heifer cow, a belief entrenched in Jewish tradition for millennia.

The significance of the Red Heifer extends beyond the boundaries of any single religion. It intertwines Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Some Jewish activists, in collaboration with US evangelical Christians who believe that the construction of the Third Temple will initiate the second coming of Jesus and Armageddon, have chosen to breed their own red heifer.

This convergence of beliefs illuminates the complex interaction among these faiths, each presenting its interpretation of the Red Heifer’s significance. For Christians, the construction of the Third Temple symbolises the anticipation of Jesus’ return and the apocalyptic event of Armageddon. Conversely, for Muslims, the potential destruction of the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock to accommodate the Third Temple remains a highly contentious and provocative issue.

Mentions of the occupied West Bank, where the Red Angus cows are raised, and the illegal Israeli settlement near the Palestinian city of Nablus, where a conference on the religious importance of the cows was held, serve as stark reminders of the enduring conflict and occupation that have shaped the region for decades.

The Spot of The Temple

Radical Jewish groups advocate for the construction of a temple on the elevated plateau in Jerusalem’s Old City, the Temple Mount, currently occupied by the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock shrine. This proposal is linked to beliefs foreseeing the arrival of the Messiah.

The ambition to erect the Third Temple atop Islam’s third holiest site, Al-Aqsa Mosque, highlights the profound tensions and potential conflicts embedded in the Red Heifer narrative. Upon examining the geopolitical landscape, various stakeholders, including the United States and its evangelical Christian community, prominently emerge. Their financial support has fuelled endeavours to breed the perfect red heifer, unveiling the global scale of the issue and the intricate interplay of interests at play.

The societal dimension holds significant weight, evident in the rise of religious Zionism in Israel and its impact on the nation’s identity and direction. This movement advocates for the Judaization of Jerusalem, unrestricted settlement in the occupied West Bank, and endeavours to resolve Jerusalem’s identity through religious means, alongside the annexation of the West Bank and implementation of policies resembling ethnic cleansing against Palestinians. Through this lens, the Red Heifer narrative emerges as a symbol of the divide between secular and religious ideologies within Israeli society, potentially leading to heightened conflict and erosion of democratic values.

A Zionist Project

The Zionist project is depicted paradoxically, juxtaposing its proclaimed role as a bastion of modernity and progress with its deep entanglement in ancient religious narratives and extremist ideologies. This juxtaposition prompts contemplation on the foundational principles of the Israeli state and its trajectory.

The Red Heifer narrative highlights how religious beliefs can shape political landscapes and ignite conflicts. Central to this narrative is the pursuit of purity and perfection, exemplified by the rigorous criteria for the red heifer. This theme extends beyond religious contexts, resonating in broader societal and political spheres where the pursuit of purity often leads to extremism and division.

Power dynamics and the involvement of global actors are also significant themes. Various nations and non-state entities, each driven by distinct agendas, shape the narrative and impact its trajectory.

Moreover, the wider implications of the Red Heifer narrative, including its effects on identity, nationhood, and the role of religion in shaping these constructs. It encourages reflection on the complexities of the Zionist project and the challenge of reconciling conflicting ideologies.

The sacrifice of the Red Heifer/Cow you hv mentioned in your article was actually ordered by Allah to the people/paternal cousins of a lone son of a wealthy man who was murdered for inheriting a huge wealth after the death of his father and was meant for identifying the murderer of the boy and when they did so after matching the exact criteria that Allah had ordered to them through Prophet Moosa (A.S), the flesh of the sacrificed cow (yellow colored and without a mark on its body) was casted upon the corpse of the boy and the boy came to life again and named the one who had killed him.

I wish you to refer to the Qur’an for exact answer.