Senior advocate Dr Rajeev Dhavan for the petitioner Jammu and Kashmir People’s Conference in the ongoing In Re Article 370 hearings, asserted that India’s unique and continent-like diversity necessitated arrangements of autonomy such as the one that existed in Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. Constitutional morality suggests that such arrangements should be preserved, Dhavan argued, reports Gursimran Kaur Bakshi.

“Article 370 is a constitutional substitute for a merger or standstill agreement, without which we are lost,” senior advocate Rajeev Dhavan argued on Day 6 of In Re Article 370 hearings.

This was immediately after he drew the attention of the five-judge Constitution Bench headed by Chief Justice of India (CJI) Dr D.Y. Chandrachud and also comprising Justices S.K. Kaul, Sanjiv Khanna, B.R. Gavai and Surya Kant to the fact that oral submissions in Indian courts were “in the nature of a dialogue”.

He pointed out that this differentiated the Indian judicial system from many others, including the US system, where most of the proceedings are carried through paperwork and oral arguments are kept to the bare minimum.

Extensive oral submissions in India, as per Dhavan, allow advocates to respond to questions “which fall from your lordships”.

He gave a few examples of such questions in the hearings in the current case.

The first example he cited was the CJI making a reference to Articles 249 and 252.

He termed the questions raised by the Bench regarding those Articles “very, very important” and said it afforded the petitioners an opportunity to build the “diversity argument”, and to argue on the lines of “transformative constitutionalism” and “basic structure”.

The second example he cited was the Bench asking a question about Article 3 and whether Article 370(3) survives. He explained that Article 370(3) has been used only twice: In Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1952 (Presidential Order C.O. 44) and The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 2019 (Presidential Order C.O. 272).

“Now the question is, if it does not survive, then how can it be used in this manner,” he said, ventriloquising the Bench.

The third example he cited was about the “confusion or misunderstanding” with respect to the status of “merger agreements”.

“The question from your lordships was, once the Instrument of Accession has been signed, was the transfer of sovereignty not complete?” Dhavan said.

Actually, it was not a question, the CJI and Justices Khanna and Kaul have, at various points in the previous hearings on the matter, expressed the view that the transfer of sovereignty was final and complete.

“Our respective submission on this, my lords, is that through the signing of the Instrument of Accession, external sovereignty is lost, but internal sovereignty is not lost,” Dhavan continued.

“That is why in Prem Nath Kaul versus The State of Jammu & Kashmir, they said the monarch was still an absolute monarch,” he clarified.

The fourth and final example he cited was that of the question posed by the Bench to advocate Zafar Shah on an earlier day of hearings on the matter.

“You asked Zafar Shah, what is it that you lost on August 4, 2019?” Dhavan said, and continued, “He promised you a list, though one answer to that is ‘everything’.”

All this after he had promised the court at the beginning of the day, “No more discussion on libraries”.

Article 370: a constitutional substitute of merger agreement

Dhavan, who is representing the Jammu and Kashmir People’s Conference, pointed out that Maharaja Hari Singh did not sign a standstill agreement with India.

As J&K did not immediately accede to the dominion of India, the maharaja proposed signing a standstill agreement in the meanwhile. Although he signed a standstill agreement with Pakistan, India refused to sign a similar argument.

Dhavan cited Prem Nath to buttress his argument that Article 370 is a constitutional substitute for a standstill or merger agreement.

The judgment states, “There can be no doubt that though this act [of signing of the Instrument of Accession] marked the second step taken by His Highness in actively associating his subjects with the administration of the State, it did not constitute even a partial surrender by His Highness of his sovereign rights in favour of Praja Sabha.”

The judgment further states: “In the result, subject to the agreements saved by the proviso, Maharaja Hari Singh continued to be an absolute monarch of the State, and in the eyes of international law he might conceivably have claimed the status of a sovereign and independent State.

“But it is urged that the sovereignty of the maharaja was considerably affected by the provisions of the Instrument of Accession which he signed on October 25, 1947. This argument is clearly untenable.”

Dhavan referred to the judgment to indicate that the Instrument of Accession made a distinction between external and internal sovereignty.

He pointed out that through the Instrument of Accession, the maharaja recognised the fact that J&K had become a part of the dominion of India.

But the maharaja did not transfer his sovereignty through the Instrument of Accession.

The process for transferring sovereignty, Dhavan pointed out, began partly because of political reasons and partly because of Article 370.

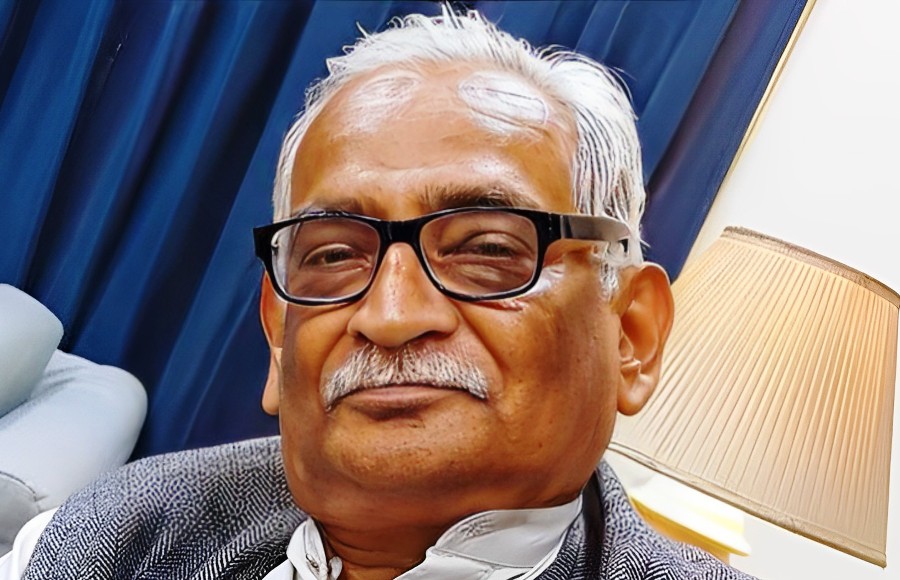

Called on Rajeev Dhavan sahib. Conferred with him along with my colleagues @bashirdar01 @ashraf_58 @AdnanAshrafMir

Dhavan sahib will argue on behalf of @JKPC_ tomorrow in the ongoing case pertaining to Article 370.

Wishing him and his team the best pic.twitter.com/EBwk9yDtp3

— Sajad Lone (@sajadlone) August 9, 2023

Political dilution of sovereignty

Dhavan then stated that in the absence of a merger or standstill agreement, subsequent changes initiated the transfer of sovereignty of J&K.

For instance, the convening of the J&K Constituent Assembly or replacing it with the governor.

Article 3: Statehood cannot be degraded

Dhavan then referred to the proviso to Article 3. According to the proviso to Article 3, no Bill altering the name or boundary of any state can be introduced without the consent of the state legislature.

Dhavan argued that the Presidential proclamation of December 19, 2018 (when J&K was put under President’s rule after being under governor’s rule for six months) virtually created an amendment in Article 3 by taking out the condition precedent of the Article.

According to his argument, since the Parliament exercised the power of the state legislature, the Parliament gave consent to itself to introduce the Jammu & Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019 during the President’s rule.

The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1954 (Presidential Order C.O. 48) added a further proviso to Article 3 which stated that no Bill for increasing or diminishing the area of J&K or altering the name or boundary of the State will be introduced in the Indian Parliament without the consent of the J&K legislature.

Nothing irreversible can be done during President rule

Further, Dhavan proposed that during the President’s rule, Articles 3, 4 and 370 cannot be invoked because they include conditionalities which are specific to the state legislature.

Elaborating on the conditionalities, Dhavan argued that neither the President nor the Parliament can be a substitute for the state legislature under Articles 3 and 4.

Dhavan then talked about the need to discipline the powers exercised by the President under Article 356. He added that Article 356 is an exception because it overrides federalism and can lead to a collapse of democracy in a state.

Dhavan pointed out that the court will have to determine whether something irreversible can be done with regard to a state while it is under President’s rule under Article 356.

Dhavan went on to refer to various powers that can be exercised by the legislature such as Articles 3 (consultative powers), 54 (right to vote in Presidential elections), 80 (elect members to the Rajya Sabha) and 243N (certain laws regarding panchayats).

Here he pointed out that the President can only exercise legislative powers which are different from other legislative powers such as the consultative powers exercised under Article 3 of the Indian Constitution.

The CJI asked Dhavan if the Parliament can enact laws under Article 246(2) during the subsistence of a President rule.

Dhavan responded by stating that the powers exercised under Article 356 are limited to legislative powers only.

He said that the Parliament can make laws under the state list but it will have to observe the conditionalities mentioned.

Dhavan further remarked that Article 356 certainly does not give the power to amend the Constitution or deprive the Constitution of its mandatory procedural requirements.

Constitution of India diverse

Dhavan referred to various provisions of the Indian Constitution to argue that the Constitution accommodates different types of special provisions.

Some of these provisions can be exercised without involving the legislature of the concerned state, but other provisions require mandatory involvement of the state legislature. Dhavan termed this “a safeguard for the federal structure”.

Dhavan referred to Articles 3, 35, 63, 164, 168 and 169 and many other provisions.

For instance, under Article 63 the legislature of the state exercises no powers. Whereas, under Article 164, the President cannot exercise powers without the state legislature.

Dhavan also referred to Article 343 read with Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution which recognises Kashmiri as a language.

He pointed out that Kashmiri as a language cannot be taken away by an executive act.

Multi-symmetric federalism

Dhavan also submitted that India’s Constitution talks about asymmetric federalism.

He referred to the Government of NCT of Delhi versus UOI (2023) wherein the court observed: “This variance in the constitutional treatment of Union territories as well as the absence of a homogeneous class is not unique only to Union territories.

“The Constitution is replete with instances of special arrangements being made to accommodate the specific regional needs of States in specific areas.”

Further, the court had stated: “Therefore, the NCTD is not the first territory which has received a special treatment through a constitutional provision, but it is another example— in line with the practice of the Constitution— envisaging arrangements which treat federal units differently from each other to account for their specific circumstances.

“For instance, Article 371 of the Constitution contains special provisions for certain areas in various States as well as for the entirety of some States.

“The marginal notes to various Articles composed under the rubric of Article 371 provide an overview of a number of States for which arrangements in the nature of asymmetric federalism are made in the spirit of accommodating the differences and the specific requirements of regions across the nation.

“The design of our Constitution is such that it accommodates the interests of different regions. While providing a larger constitutional umbrella to different states and Union territories, it preserves the local aspirations of different regions.

“‘Unity in diversity’ is not only used in common parlance, but is also embedded in our constitutional structure. Our interpretation of the Constitution must give substantive weight to the underlying principles,” the judgment had averred.

Transformative constitutionalism

Dhavan told the court that the reading of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution so far has been like a statute whereas, the Constitution has to be read like a living document.

Dhavan also referred to the notion of transformative constitutionalism invoked in Navtej Singh Johar versus Union of India (2018), in which case it was observed: “The ultimate goal of our magnificent Constitution is to make right the upheaval which existed in the Indian society before the adoption of the Constitution.”

The Supreme Court in the State of Kerala and another versus N.M. Thomas (1975) and others observed that the Indian Constitution is a great social document, almost revolutionary in its aim of transforming a medieval, hierarchical society into a modern, egalitarian democracy and its provisions can be comprehended only by a spacious, social- science approach, not by pedantic, traditional legalism, Dhavan contended.

The whole idea of having a Constitution is to guide the nation towards a resplendent future. Therefore, the purpose of having a Constitution is to transform society for the better and this objective is the fundamental pillar of transformative constitutionalism, Dhavan averred.

The report was republished as part of an arrangement with The Leaflet. The original report was published here

The Story So Far

Day 1; Day 2: Day 3; Day 4, Day 5