by Javaid Iqbal

Except in Kashmir, nowhere do people believe that unless they abandon their mother tongue and embrace English as the sole language of instruction, their future is doomed.

If you can read this article, you are part of the Indian elite that can understand English. Only 10 per cent of the population in India can understand this language. English is also now an aspirational for all Kashmiri’s; private schools have unspoken admission requirements: at 3 and 4, the child should be able to speak basic English. Parents stretch their family budgets so their children can study in English medium schools.

English is also one of the most crucial determinants of social status, income, prestige, and employment. Parents line outside private English medium schools in the early hours of dawn to register their children for admission in these schools. The language has created a new caste system in our society. There is no doubt that English is unifying us with the rest of the world, but it also alienates us from our familial and cultural roots.

Only four per cent of the population in India speaks the language fluently. This minor percentage sets the plan for how the rest of the country should provide education to the poor and other backward communities and dominate mainstream media. This obsession with English is why we will never see an angry TV debate on why India had 2.4 million TB cases in 2019 as the targeted audience is not affected.

A 2014 report from the Centre for Research and Debates in Development Policy in India found those who could speak fluent English earned 34 per cent higher wages than those who had some fluency. In the 21st century speaking this global language does have advantages, but, in a place, as diverse and low resource as India, it has done more harm than good. The English language was meant for helping the administrative needs of the British colonial masters; unfortunately, we still suffer from a colonial hangover. Even doctors during hospital rounds discuss patient details in English while the patient is lying in bed, agonizing over his fate without following a word of what is going on.

Most Indian children leave school without the basics of old-fashioned reading, writing, and arithmetic, in any language. The policy of learning English has smothered India’s regional languages, marginalized linguistic and ethnic minorities, and perpetuated income inequality. Since 1950, nearly 250 Indian languages have gone extinct, with another 40 endangered today. Even India’s most abundant regional languages, such as Marathi, Telugu, and Tamil, have seen fluency decline by nine per cent, 14 per cent, and 16 per cent between 1971 and 2001.

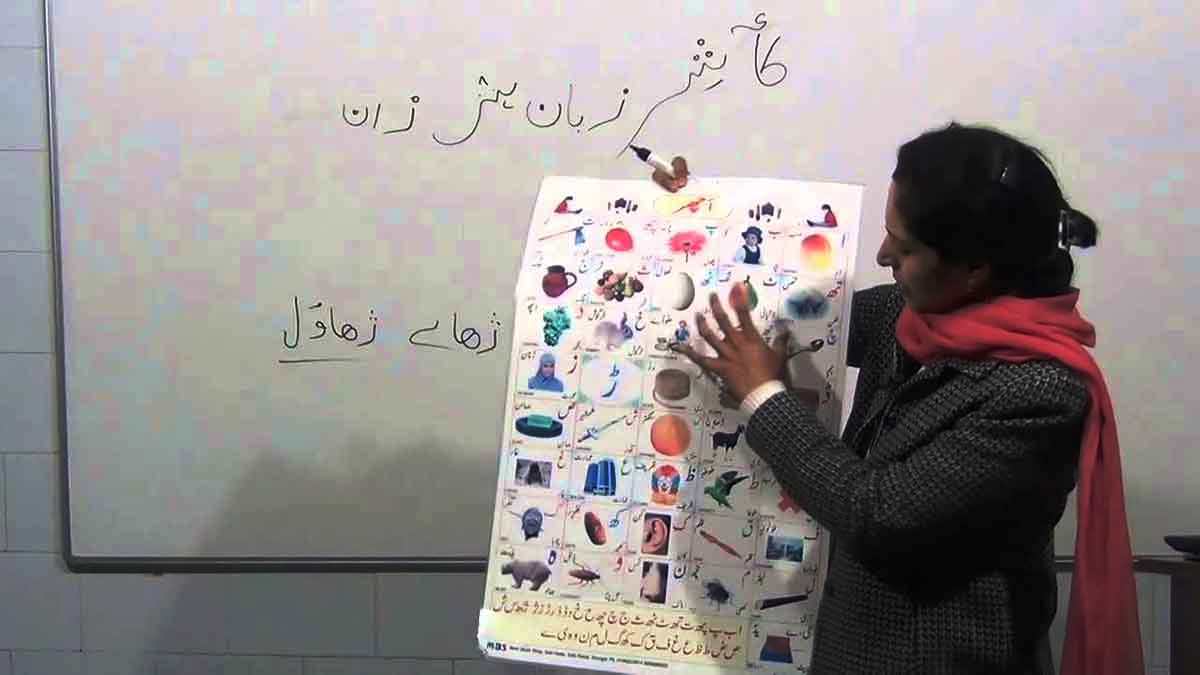

Kashmiri as a language is also under threat, with many in the younger generation not wanting to speak the language and many people having a sense of shame while speaking in the mother tongue. Unfortunately, people who talk in Kashmiri are looked down upon, and as a result, many families are reluctant to teach Kashmiri to their children. And parents occasionally reprimand their children for speaking in the “vernacular” — even in their own homes. The language is now deeply entrenched in our society – when was the last time you went out to eat, and the menu was not in English?

Only children from relatively affluent families learn anything at English-medium schools. These are the children that belong to the self-perpetuating elite. First, because English is almost everyone’s second language in India, only children from affluent families hear or read enough to learn concepts in it by the time they begin primary school. Most other children are burdened with learning a new language while learning new ideas, leading to minimal learning outcomes. As a result, a shockingly large number of Indian students are functionally illiterate, the result of studying in a language they have not mastered.

There is evidence that children process knowledge and a second language, such as English, better when they have a sound educational base in their native language. Both vernacular and English medium private schools have convinced parents that they are giving importance to learning in and of the English language. However, finding quality teachers who can effectively teach subjects in English, at salaries near minimum wages is an uphill struggle for schools in low-income areas. The textbooks are primarily written for English medium schools in urban areas. They are not apt for students or teachers in rural areas, which lowers the teaching standards in English medium schools in rural areas, resulting in students performing way below their potential.

Developing foundational skills is a complex issue as there are a large number of factors that impact a child’s ability to learn: gender, race, place of birth, or the social and economic condition of their family – all of these lead to wide disparity in children’s capabilities and levels of exposure. In a country as diverse as India, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to improve foundational literacy.

All development begins with education, and education, of course, stems from language. Maintaining your first language is critical to your identity and contributes to a positive self-concept. The Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) reiterates that studying your mother tongue after childhood helps you learn how to value your culture and heritage.

When children who do not speak even a minuscule of English at home are taught in English during their initial years of schooling, the whole learning process is impaired; instead, if they learn in their mother tongue first and after that English, they will learn both languages much better. One of the biggest reasons these kids learn by rote without understanding a thing is because they are taught subjects like mathematics and science in English, the result is that they pass the examination but end up as unemployable graduates, which is a tremendous loss, both at the individual level and the level of society. We need to understand the difference between English as a subject and English as a medium of instruction. The children that do not learn English end up not learning anything.”

Except in Kashmir, nowhere do people believe that unless they abandon their mother tongue and embrace English as the sole language of instruction, their future is doomed. If our language and culture have to survive, we have to induce a sense of pride in the way we speak our language.

(The author is a Global fellow at Brandeis University USA. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Kashmir Life.))