Medieval Kashmir witnessed massive shifts in the region’s faith, politics and economy. Credit goes to historian Prof Mohibbul Hasan for offering Kashmir a book that helps understand the crucial era of Kashmir better, writes Muhammad Nadeem

Following his retirement from Jamia Millia Islamia in July 1970, Prof Mohibbul Hasan received an offer from Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Ghulam Muhammad Sadiq to chair the History Department at the University of Kashmir. Hasan’s notable scholarship, particularly his work on Kashmir under the Sultans, likely garnered this offer. Tasked by Sadiq to document the history of the Dogra misrule, Hasan embarked on research trips to Europe (England and France) for six months to collect the relevant material.

Hasan’s scholarly work, Kashmir Under the Sultans, was published by Iran Society, Calcutta, in 1959. At the behest of Prof Abu Mohammed Habibullah from Dacca University, Hasan embarked on a journey to write a monograph on the Kashmir Sultanate. Chief Secretary MK Kidwai hosted him during his research trip to Kashmir in 1952.

A Pioneering Study

This pioneering study provided the first comprehensive exploration of Kashmir’s history, tracing its evolution from the 14th-century Sultanate to its absorption by the Mughals in the 1580s. From diverse sources such as Persian and Sanskrit texts, Kashmiri literature, European accounts, and archaeological findings, Hasan illuminated the flourishing Kashmiri culture under the Sultans, ultimately subsumed by Mughal rule. His analysis unveiled the origins of a distinct regional identity, offering invaluable historical context for understanding Kashmir. He fondly remembered his time in Kashmir but regretted being unable to complete Sadiq’s assignment due to declining health.

While Kashmir under the Sultans possesses some shortcomings, its significance cannot be overstated. It stands as the first scholarly attempt to reconstruct the history of Kashmir from the establishment of the independent kingdom of Muslim sultans to the Mughal conquest in 1586. Hasan offers an objective analysis of the political events in Kashmir, including internal discord and civil war under the Chak rulers, which weakened the administration and adversely impacted the economy.

Regarding the Mughal conquest of Kashmir, Hasan notes that Kashmir’s isolation ended, bringing it into the sphere of Indian politics. Consequently, Kashmir lost its distinct identity and became akin to any other province of the Mughal Empire, with Srinagar relegated to the status of a provincial town.

Discussing the impact of the fall of the Sultanate on Kashmiris, Hasan observes that the ruling families of Chaks, Magres, Rainas, and Dars were supplanted by a hierarchy of Mughal officers tasked with administering the region. Besides, the defence of Kashmir was assumed by the Mughals. Consequently, Kashmiris gradually lost their martial spirit and fighting prowess, which they had demonstrated in numerous conflicts against invaders.

Sourcing The History

Hasan begins by highlighting the loss of many early chronicles in Sanskrit and Persian from the Sultanate period, lamenting these irrecoverable gaps in historiography. He then classifies the surviving sources into various categories: Sanskrit accounts by court poets Jonaraja, Srivara, Prajyabhatta, and Shuka; early Persian histories; travelogues of Central Asian and Mughal figures; provincial chronicles; and hagiographies documenting the influence of Sufi saints in spreading Islam in Kashmir.

Notably, Hasan b Ali Kashmiri’s history, commissioned by a descendant of the Sultanate nobility, stands out among the Persian sources. With Kashmir’s incorporation into the Mughal Empire, historical writings increased, including contributions from Nizamuddin, Abu’l Fazl, and Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah Ferishta, who integrated sections on Kashmir in their histories of Akbar’s reign. The Tibetan historian Kun-dga’-snying-po provides an external view of Sultan Sikandar’s persecution of Buddhists. Ferishta also utilised Mirza Haidar Dughlat’s Tarikh-i-Rashidi, which recounts Dughlat’s firsthand experiences during his brief occupation of Kashmir.

European travellers like François Bernier offer later Mughal-era observations on Kashmir’s distinctive culture. Special recognition is given to Haidar Malik Chadura, a historian serving the Sultanate nobility. His History of Kashmir incorporates diverse sources and family traditions, providing a uniquely authentic perspective.

Hasan also examines how proximity to power and sectarian ties influenced historians like Jonaraja, Srivara, and Haidar Malik. He explores the complex interplay between history, memory, and politics in medieval Kashmir, where sacred and secular traditions competed for dominance.

The sources together paint a rich tableau of Kashmir’s syncretic history and culture, blending Sanskrit and Persian scholarship with Sufi-Rishi spirituality. Hasan investigates the changes brought by Islamic rule from the 14th century, highlighting the persistence of Hindu, Buddhist, and Central Asian cultural elements. The chroniclers detail Sultan Sikandar’s controversial efforts to convert his subjects to Islam and purge Persianate culture of Indic influences, a memory that evoked mixed reactions across religious divides.

Hasan’s Craft

Hassan’s work captures the cultural flourishing and political centralisation under Sultan Zainulabidin, followed by the internecine strife after his death. The Sultanate weakened due to factional claims to sovereignty and the expeditions of Central Asian warlords like Mirza Haider Dughlat. It eventually eclipsed after Akbar’s annexation and integration into the Mughal sphere.

The Mughal historians provide external perspectives to balance native chroniclers’ accounts and mark a shift from Persian-Sanskrit traditions to early modern Indo-Islamic models. Hassan evaluates the corpus using criteria like testimony, corroboration, critical judgment of bias, and factual accuracy, demonstrating analytical parameters and textual mastery akin to modern historiography.

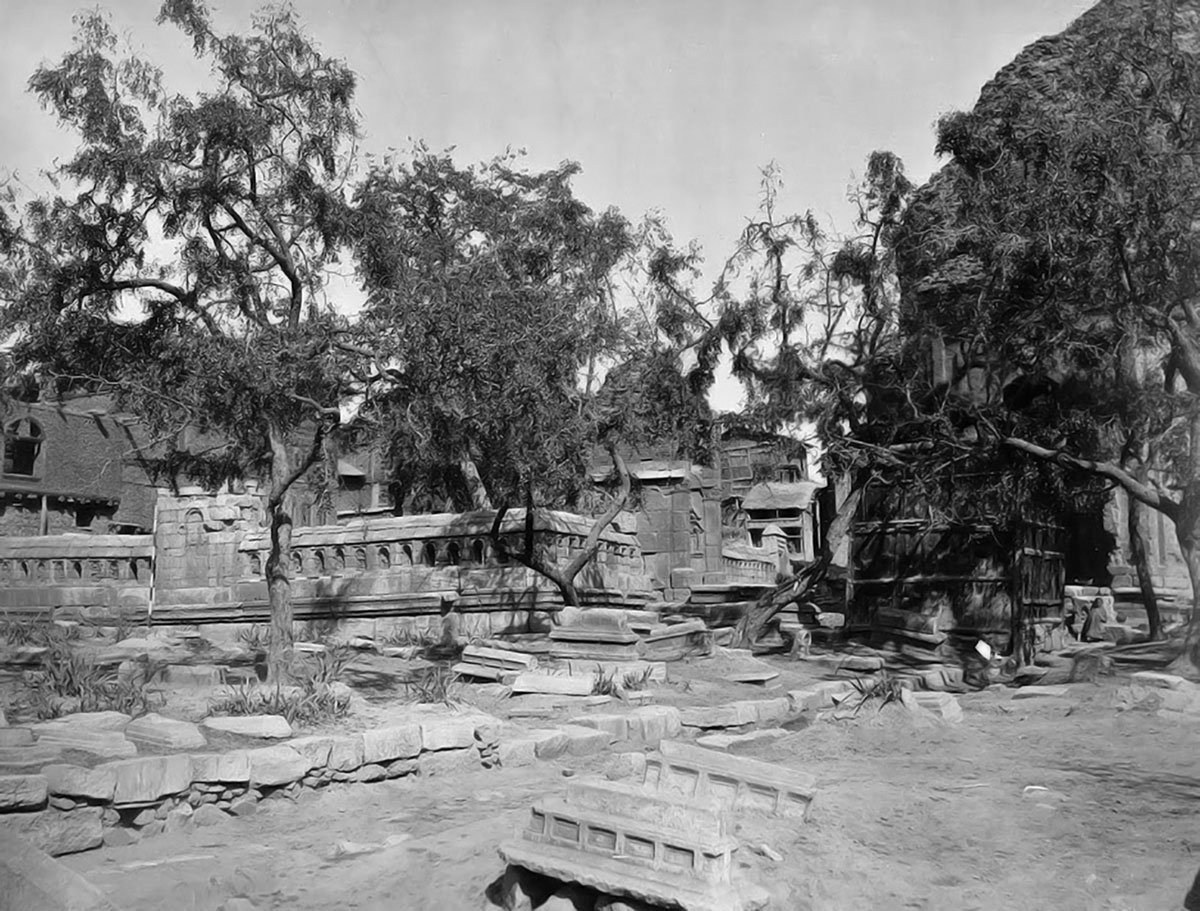

Hassan covers a broad range of topics, including politics, society, economics, cultural norms, and religious developments. He mines surviving remnants of the past while cautioning against archaeological evidence limitations. He also analyses coins and architecture that survived the destruction. However, textual archives remain the core foundation for any authentic medieval Kashmir history.

By assessing strengths and conditioning factors, Hassan sets scholarly standards for interpreting original texts and constructing historical narratives sensitive to cultural contexts and ideological potential for distortion. The book offers a roadmap for inquiring into Kashmir’s contested medieval history, featuring a detached analytical lens, contextual sophistication, erudite commentary, and fragments of political and cultural history woven into the assessment.

The Metamorphosis

Hasan’s work provides a historical account of the decline of Hindu rule and the rise of Muslim rule in medieval Kashmir, spanning the 8th to 14th centuries. It chronicles Kashmir’s encounters with invading Arab and Turkic forces, the internal decay of its Hindu dynasties, the devastating Mongol invasion of 1320, and the establishment of Muslim rule under Rinchan, a Ladakhi Buddhist refugee who converted to Islam.

Hassan highlights geography as a key factor in Kashmir’s history, with its mountainous barriers allowing extended periods of isolation and exposure to invasions. He emphasises how weak and corrupt Hindu kings like Suhadeva ultimately betrayed their subjects, losing the Mandate of Heaven and leaving the populace indifferent to defending Hindu rule against foreign incursion.

The account is not simplistically critical of Hindu rule nor glorifying the succeeding Muslim dynasty. It highlights strong Hindu rulers like Lalitaditya and Jayasimha, whose reigns brought stability and prosperity. Rinchan won over Kashmiris by befriending former Hindu rivals and marrying into local families, rather than relying solely on his Tibetan followers. His reputation for protecting the people from bandits during the Mongol occupation enabled his rise in place of the fleeing Hindu ruler Suhadeva.

One can discern profound themes concerning cultural and spiritual transformations between the lines. Kashmir’s transition from Hindu/Buddhist syncretism to the new solidarities of the Muslim community, signalled by Rinchan’s mosque construction, is emblematic. Rinchan’s spiritual journey from his Tibetan Buddhist upbringing to his conversion to Islam serves as an allegorical tale, reflecting wider societal desires for new ideological alternatives to the corruption and constraints of decaying Hindu feudalism.

Hassan points out that the hold on religion stems not just from theological claims but also from its power to forge new communities and identities. The failures of Rinchan’s Brahman interlocutors to defend their belief system and accommodate his questioning speak to profound crises of legitimacy faced by civilisations in decline. It took outsiders like Bulbul Shah to re-enchant Kashmiri souls and catalyse religious transformation.

The starkness of famine, destruction, and former elites begging barefoot amid ruins in the wake of Mongol devastation shattered old pieties and highlighted the poverty of men relying purely on mortal arms without divine aid. Such pivotal junctures of breakdown offer the profound potential for midwife cultural rebirth if grasping leaders can leverage the interregnum to offer alluring new visions of shared destiny that ordinary people can make their own. Rinchan’s political astuteness in aligning himself with Kashmiri interests rather than just Tibetan conquest enabled the rise of the Sultanate built on Kashmiri participation.

Paid obeisance at Yousuf Shah Chak’s grave in Bihar. As the last muslim ruler of Kashmir, his resting place symbolises the ties between Kashmir & Bihar. Unfortunately the site is in absolute disrepair & ruins.Appeal @NitishKumar ji to take steps to preserve this relic of history pic.twitter.com/ZbWUXFphnd

— Mehbooba Mufti (@MehboobaMufti) June 22, 2023

Mughal Occupation

Hasan chronicles the tumultuous end of the Chak dynasty’s rule over medieval Kashmir, culminating in the region’s annexation by the Mughal Empire under Akbar. At the heart of the account lies an analysis of the last Kashmir ruler, Yusuf Shah Chak.

Yusuf Shah is initially depicted in a sympathetic light as a man of refined tastes patronising the arts and sciences. However, a deeper exploration reveals fatal flaws that directly catalyse Kashmir’s downfall – an obsessive paranoia about rebellion leading to despotism, and a paralysing fear of the rising Mughal power prompting appeasement instead of self-assertion.

Hasan details Yusuf Shah’s ruthless suppression of internecine conflict within Kashmir, as he blinds, executes, and mutilates kin and courtiers. Ironically, this atmosphere of fear and mistrust triggers more defections and revolts, continually eroding the kingdom’s stability.

In contrast, the later sections reveal Yusuf Shah’s passive acquiescence to Mughal authority despite his subjects’ willingness to resist. Though initially avoiding Akbar’s imperial summons, geostrategic realities soon close in. Against the passionate exhortations of his people, Yusuf Shah compromises Kashmir’s sovereignty and surrenders to Akbar, sealing its annexation.

These scenarios spotlight the tension between internal consolidation and external pressure in statecraft. Kashmir’s history shows that without astute state-building cementing popular legitimacy, even extensive material advantages cannot compensate against adverse shifts in power dynamics. The Chaks’ political mismanagement squandered their strategic assets.

The detailed battle scenes reveal the odds were hardly insurmountable despite Mughal rhetoric. Dogged defenders repeatedly repel numerically superior Mughal forces, leveraging the environment and motivating soldiers through appeals to identity. Tragically, Yusuf Shah’s many blunders and defects proved catastrophic at the most critical juncture.

The Mughal annexation hence appears almost accidental, enabled entirely by the Kashmiri implosion. Akbar tried diplomacy to win Kashmir as a vassal, but Yusuf Shah’s willing surrender made the actual occupation feasible. However, lingering resentment created complications, as Akbar’s reneging on assurances to Yusuf Shah violated his pragmatism and ethics, fuelling mistrust.

Beyond underscoring elite decadence and decay, the fall of the Chaks marked the end of Kashmir’s medieval age. Its incorporation into the Mughal imperium portended greater integration with emergent all-India economic and administrative networks, signifying the clash between feudal isolationism and modernising centralisation.

Tolerance and Fusion

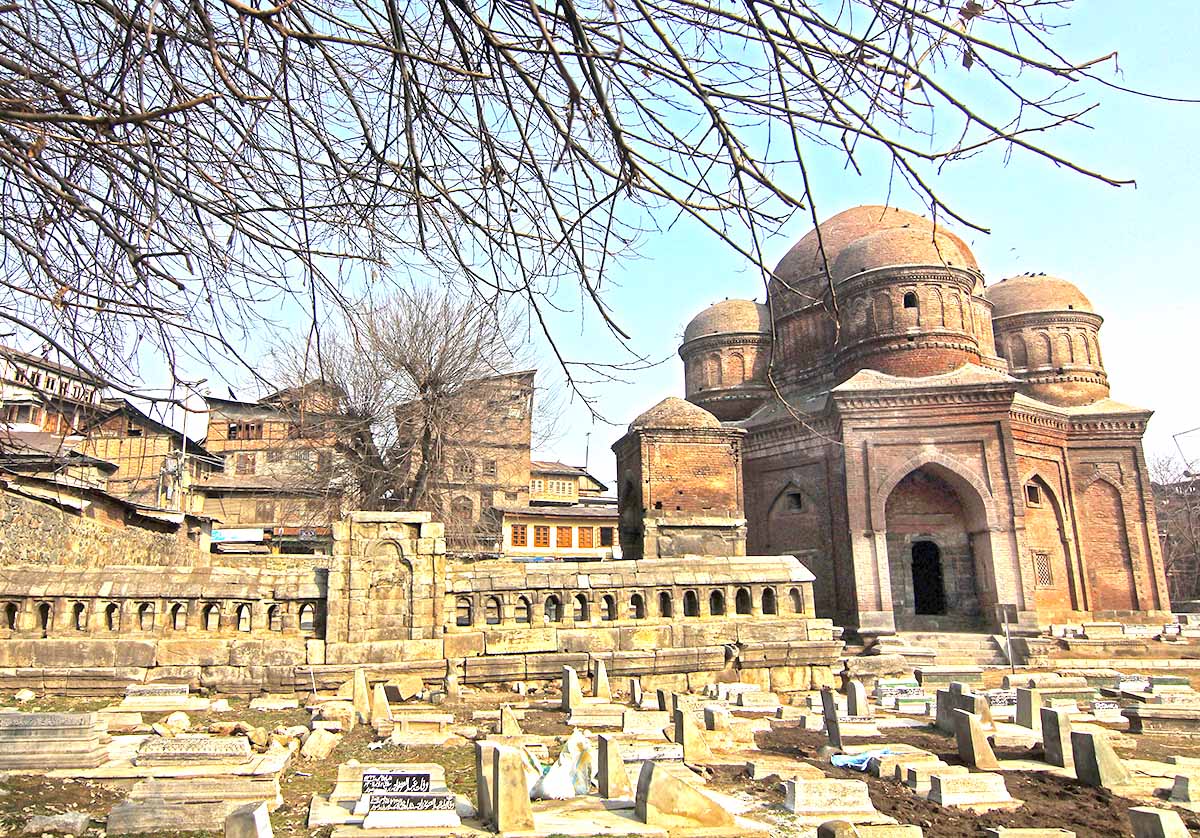

A striking theme in the book is the fusion of diverse cultures that produced a unique Indo-Persian synthesis. With the influx of Muslim missionaries, administrators, artists, and traders from Persia and Central Asia, Persian language and cultural forms permeated Kashmiri society. Local Sanskrit traditions also endured, nurtured by Hindu scholars and institutions under tolerant Muslim rulers. Thus, Kashmir emerged as a melting pot where Islamic cultures amalgamated to forge new expressions in language, literature, arts, and architecture.

Hasan identifies Kashmir’s prosperity under the early Sultanate rulers, who promoted economic development through extensive public works and encouraged specialised crafts and overland trade networks. Agricultural productivity was enhanced through hydro-engineering schemes, and villagers benefited from reduced taxes and state relief in times of famine. Kashmir became an international entrepot, exporting locally manufactured goods while facilitating Central Asian trade with the Indian subcontinent. Through vivid portrayals, from the intricate goods sold in marketplaces to the caravans trekking through mountain passes, the magnitude of medieval Kashmir’s commercial economy is emphasised.

In tracing political history, Hasan analyses the complex interplay of personality, ideology, and court intrigue in power struggles. The strengths and failings of successive rulers are assessed in the context of their times. Periods of stability and good governance stimulated cultural advancement, while prolonged unrest and conflict took a heavy toll on society.

The flowering of Persian language and literature is examined, contextualised by the influence of Sufis who propagated its elegance and spiritual potency. Eminent poets, theologians, and scientists thronged the courts of rulers like Zainulabidin, nurturing Kashmir’s intellectual life. Technical training in paper-making, textile manufacturing, and other practical arts was encouraged. Monasteries and schools proliferated, with learned scholars attracting students from distant lands.

The efflorescence in language and literature catalysed innovations in arts, architecture, crafts, and music. Hasan provides glimpses into Kashmir’s cultural vibrancy during the medieval centuries, referencing masterful yet long-vanished works in painting, calligraphy, sculpture, embroidery, and glazed tilework. Their ephemeral survival spotlights the loss inflicted by successive conquests and unremitting conflict.

The detailed accounts of political events, commercial regulations, and taxation policies sometimes seem excessive, interrupting the flow and human drama underlying the chronological narrative. While enhancing our understanding of the period, the profusion of facts can overwhelm readers interested in cultural or social history.

Although Hasan displays sound scholarship, there are vestiges of colonial-era Orientalist perspectives in descriptions of cultural forms and religious developments, interpreting these through Western conceptual frameworks. Occasionally, indigenous categories and historical contexts are bypassed, embedding prevailing stereotypical assumptions.

Through its expansive scope and attention to specifics, the book reconstructs a dynamic vision of Kashmir during a culturally vibrant epoch, revealing a society where cultural and economic forces thrived amidst political instability. It opens windows into a multifaceted medieval world where diverse influences intersected to produce singular expressions of creative genius that endure in Kashmir’s living traditions. Hasan compels us to rediscover and reappraise Kashmiri civilisation at the zenith of its glory.

Rise of Sultans

Hasan offers insights into the dynamics of political consolidation, cultural assimilation, economic orientation, and social transformation that accompanied the establishment of Muslim rule in the scenic Himalayan valley.

He attributes the rise of the Sultanate to the internal decay of the previous Hindu dynasty rather than any concerted foreign invasion. The indigenous kings had become ineffective, while feudal lords grew powerful and unruly. The people, suffering under excessive taxation and lawlessness, yearned for stability. In this milieu, the ambitious Shah Mir, despite being a foreigner, was able to entrench his authority. The relieved populace welcomed the new administration. Shah Mir and his descendants adopted a deliberately secular orientation, blending Kashmiri, Persian, and Central Asian traditions to pioneer a composite culture. Their pragmatic governance focused on restoring order, spurring economic growth, and promoting the arts.

The high point was reached during the benign reign of Zainulabidin, celebrated as the most enlightened and humane ruler Kashmir had seen. He reduced taxes, improved infrastructure, and delivered impartial justice, enabling peaceful coexistence between Hindus and Muslims. He promoted trade, introduced fiscal reforms, patronised crafts, and assembled a coterie of scholars. However, succession was hotly contested. As later Sultanate rulers weakened, the old feudal elements resurfaced, leading to power struggles. The rival Chak clan eventually displaced the Shah Mirs.

Initially energetic, the Chaks also grew indolent and autocratic over time. Court intrigues and sectarian tensions increased, plunging the country into chaos and civil wars. Ambitious rebels invited Mughal intervention from the neighbouring plains. After initial resistance, the last defiant Chak ruler was defeated and killed by Akbar’s Mughal army. With the conquest of 1586, Kashmir lost its separate political identity and cultural vibrancy. The closing of her mountain gates ended Kashmir’s age-old isolation, exposing her to the winds of change across the subcontinent.

Hasan provides a coherent narrative linking medieval Kashmir’s fortunes with her rulers’ capabilities and compulsions. His research is grounded in indigenous sources and accounts of foreign visitors. He is sensitive to the complex interplay between Kashmir’s distinctive physical features and her political trajectory. His balanced assessment of the regimes avoids both undue romanticisation and unfair vilification. The extensive range of topics covered — from agricultural practices to military organisation, from religious thought to gender equations — is noteworthy. However, the links between some thematic discussions could have been tighter, and occasional repetition of issues is present.

Hasan largely succeeds in giving us a judicious insider’s perspective on an eventful period in Kashmir’s history. There may not be great heroes and grand victories, but in the stories of the enterprising Shah Mirs, the sagacious Zainulabidin, the warring feudal chieftains, and the doomed Chaks, we discover something profound about the human condition — its aspirational highs and abyssal lows. The tragic denouement of the loss of sovereignty continues to haunt the Kashmiri psyche centuries later. Ultimately, through its themes of political ambiguity, cultural synthesis, and existential fragility, the book illuminates dimensions of Kashmir’s past that still cast their shadow on her present.

1. The ten storey wooden houses of Kashmir that Kalhana speaks about !!! An AI generated image of how these houses may have looked like, by a colleague Mehran Qureshi (who is apparently not happy with AI). But, then the limitations of AI are clear. Dependent upon visual prompts, pic.twitter.com/GbEFaKyAYC

— Hakim Sameer Hamdani (@HamdaniSameer) November 29, 2023

Harmony and Hybridity

Several interwoven themes emerge. First is the gradual, albeit contested, spread of Islam in Kashmir facilitated by Sufi saints and missionaries from Central Asia and Persia. Second is the syncretic evolution of Hindu and Islamic cultures, with each religion influencing and transforming the other. Third is the relative harmonious coexistence of Hindus and Muslims under largely tolerant Sultans who presided over a syncretic court culture.

The author contends that the success of Islam in Kashmir, compared to other parts of India, owes to unique social conditions. Buddhism had already weakened the orthodox Brahmanical order. Caste rules had relaxed, eroding barriers to the influx of foreign ideas. A spiritually restless population, disillusioned with sectarian Hinduism and ritualistic Buddhism, yearned for an egalitarian faith centred on ethical monotheism and mystical realisation of the Divine.

The Sufis filled this spiritual vacuum by propagating Islam’s simple, caste-less creed focused on unity of God and equality of believers. Leading luminaries like Sayyid Ali Hamadānī commanded mass appeal, securing numerous converts from all social strata. Although the Sultans publicly patronised Sufis, they quietly condoned Hindu customs and rarely intervened in matters of religion other than sporadic attempts by a few zealous Sultans to impose Islamic orthopraxy.

As more natives embraced Islam, creating a Muslim majority by the 16th century, Hindu and Islamic cultures continually cross-pollinated. Hasan shows how Hindus adopted Islamic manners, dress, and cuisine but retained ancestral customs regarding marriage, family life, and festivals. Similarly, Kashmiri Muslims preserved superstitions, revered saints of both faiths and participated in Hindu religious celebrations, although Islamic law technically forbade these practices.

This religious and cultural fusion extended to the arts, architecture, literature, and music. Local variants of Perso-Arabic script incorporating Kashmiri sounds emerged to record the Kashmiri language in poetry and prose. Indigenous wooden architectural styles blended Islamic structural elements, seen in exquisite mosques across Srinagar and countryside shrines. Sufiyana classical music fused Persian, Turkic, and Indian melodic modes, instruments, and rhythmic patterns into a syncretic performance tradition alive today.

Hasan adopts a generally sympathetic stance toward this cultural hybridity. He balances his analysis by highlighting complaints raised in contemporary Hindu chronicles that bemoaned the erosion of ancient customs under Muslim rule. However, he contextualises their protests as natural opposition to the influx of foreign ideas upending tradition, somewhat analogous to British imperialists deriding Indian culture.

Hasan credits Kashmir’s historic openness to outside influences, from ancient Silk Road networks to peripatetic Buddhist and Hindu ascetics, with cultivating an appreciation for cultural diversity. This explains Kashmiri society’s readiness to adapt external customs and ideals without compromising religious and regional identities—an argument affirmed by Kashmir’s present role as an example of religious pluralism in the subcontinent.

The author’s extensive mining of medieval Kashmiri chronicles, court histories, biographical compendiums, and travelogues in Persian, Kashmiri, and Sanskrit is the book’s most outstanding feature. By foregrounding native historical voices and triangulating their accounts, the narrative achieves reliability and balance in depicting a politically tumultuous but culturally vibrant era.

The book’s insights presage contemporary debates about hybridity induced by globalisation and inform historical theories on how Islam succeeded among Indic civilisations compared to Semitic cultures. The text reminds us to appreciate the subcontinent’s genius for organically integrating foreign traditions on its terms—a perspective critical for healing divisions along religious lines in Kashmir and beyond. Its implicit message asserts the urgency of cultivating a pluralistic, syncretic national culture in India rooted in shared regional idioms that harmoniously blend the subcontinent’s diverse philosophical, literary, and artistic heritage.

The Intellectual Sultan

Zainulabidin (1420-1470 CE), the eighth Sultan of Kashmir, emerged as a wise and benevolent ruler dedicated to justice, religious tolerance, and the welfare of his subjects. Though he lacked the martial prowess of his father Sikandar, known as the infamous ‘iconoclast,’ he compensated with a mild temperament, compassion, and intellectual inclination. Hasan depicts him as a scholar-king well-versed in several languages, a patron of arts and letters, and even a bit of a polymath-inventor.

Politically, Budshah (Great King), as Zainulabidin was known, adopted a conciliatory policy towards Kashmir’s Hindu majority after the religious persecution unleashed by Sikandar. He allowed the rebuilding of destroyed temples, reduced the jizya tax to a nominal sum, appointed Hindus to high office based on merit, and even participated in their festivals, thus promoting communal harmony.

On the economic front, the Sultan took active measures to develop agriculture and expand cultivated land through irrigation works like canals and artificial floating islands, making Kashmir self-sufficient in food with stable prices. Through state sponsorship, incentives, and technology transfers, Budshah also promoted various crafts and cottage industries—paper, textiles, shawls, woodwork, and firearms. These industries became familial enterprises passed down through generations. Along with agricultural surplus, these handicraft products brought prosperity through internal and external trade.

So a bit of fun with AI, to generate images of Sultan Zain ul Abidin of Kashmir, in his old age, sad and alone- with rosary in hand, framed against a papier mache ceiling of his palace. pic.twitter.com/SsY2Qm0O74

— Hakim Sameer Hamdani (@HamdaniSameer) March 2, 2024

Hasan explores how Budshahpatronised scholarship and the arts. His court attracted talent from Central Asia and Iran, and he even founded a translation bureau facilitating the transmission of knowledge between Sanskrit and Persian. The Sultan emerges as a paragon of the Persianate Mirrors for Princes’ tradition, blending Islamic and Indic modes of statecraft and governance.

However, Hasan suggests that Budshahwas rather ineffectual as a military leader, overly lenient with his rebellious sons, and unable to prevent factionalism among the nobility in his old age.

Viewed against the traumatic memory of Kashmiri Hindus, the harmonious picture presented here facilitated their peaceful accommodation with the Sultanate. But it also papered over fissures that would resurface later. When the external stability established by Budshah weakened after his death, fault lines emerged among his successor dynasts, nobility, and the subject populace.

Transmission and Transformation

Hassan provides insight into the emergence and evolution of the Nurbakhshiyya Sufi order in Kashmir during the Sultanate rule. The author traces the origins of the order to its founder, Sayyid Muhammad Nur Bakhsh, in Persia. Nur Bakhsh, claiming spiritual descent from an earlier Sufi master, proclaimed himself the Mahdi and Imam of his time. His unorthodox views brought him into conflict with the Timurid ruler Shah Rukh, resulting in long imprisonment. After Shah Rukh’s death, Nur Bakhsh was freed and eventually settled in Ray, where he died. His son Shah Qasim succeeded him as leader of the fledgling Nurbakhshiyya order.

The Nurbakhshiyya doctrines combined Sufi mystical ideas like divine light, esoteric knowledge transmitted from Ali, and the goal of fana (merging oneself into the Divine) with Shiite concepts like the sanctity of the Imams. The order aimed to revive Islamic teachings and eliminate religious innovations that had appeared over time. The religious practices of the order reflected this synthesis, resembling those of other Sufi tarīqahs but with a special emphasis on Muharram rituals.

The order entered Kashmir with Mir Shamsuddin Araqi, a Persian envoy sent in 1481 by the Timurid ruler of Herat. Using his position, Shams secretly spread Nurbakhshi teachings and made a few converts, but hostility from the orthodox ulema soon forced him to leave Kashmir. After the death of his former patron, Shamsuddin transferred his allegiance to Shah Qasim in Ray and was directed to return to Kashmir to proselytise actively. Hassan infers Shamsuddin’s success in making prominent converts like Musa Raina, enabling him to build a Nurbakhshiyya khanqah and gain a stronger foothold in Kashmir.

Opposition soon resurfaced, led by the powerful minister Sayyid Muhammad Baihaqi, who had initially opposed the khanqah‘s construction. Persecution from Baihaqi forced Shamsuddin to temporarily leave for Baltistan before he could return to Kashmir and propagate freely after Baihaqi’s death. Hassan shows how Shamsuddin’s support from subsequent administrations led by his disciples ensured the order’s growing strength despite later persecutions under Mirza Haidar Dughlat. The order underwent doctrinal changes under rising Safavid influence from Persia, becoming increasingly Shiite until the two were hardly distinguishable. Ultimately, the Kashmiri Nurbakhshis were either absorbed into Sunni or Shiite Islam.

By tracing the Nurbakhshiyya from Persia to medieval Kashmir, the author sheds light on the transmission of religious ideas across frontiers. The order’s persistence despite political opposition speaks to the pervasive ways mystical currents permeated popular religious practice. By tracking doctrinal changes over time, Hassan also highlights shifts in Persianate cultural connections with Central Asia and links them to the flexible reinvention of religious identities. The broad historical context enables a deeper analysis of the Nurbakhshis and the wider phenomenon of Sufism taking uniquely syncretic forms at its margins.

Hassan constructs his narrative using Persian chronicles and works associated with the order in Kashmir. This lends the account immediacy and intimacy while also allowing cross-verification of dates and chronology. Frequent names, terms, and foreign phrases related to Sufism and mystical practice firmly embed the discussion for a scholarly audience but may benefit from clarification for general readers. Providing transliterated terms in parentheses would increase accessibility. While the focus remains on Kashmir, analysing comparative developmental trajectories for the Nurbakhshi order in neighbouring regions could have enriched perspectives further.

Best History

The book offers a granular, archive-driven investigation into understudied facets of Kashmir’s Persianate past. By focusing on religious history, it compels re-examination of syncretism, dissent, and the pragmatism underlying doctrinal evolution, pushing disciplinary boundaries. The themes explored open avenues for further research on Kashmir as a zone of mystical encounters, accentuating its cultural DNA. This academic rigour, combined with the excerpt’s clear structure and fluid style, renders it both an edifying read and a seminal reference work. It serves as an exemplar for reconstructing opaque but formative processes that challenge linear assumptions about religio-cultural change in the medieval period.