Had Babur’s cousin, Mirza Haider Dughlat not invaded Kashmir, the central Asian and Mughal history would have been less understood, nearly half a millennium after he was assassinated in Budgam after slightly over a decade long rule. Masood Hussain explains the huge relevance that Dulaty still has in Kazakh-Delhi relations

In early 2015, Kovtun Olga Alexeyevna, a teacher of Kazakh history at Karaganda Medical University, took off on an unprecedented journey. Accompanied by a Kashmiri, Parvaiz Dar, who had barely graduated from her university, Kovtun wanted to trace the eternal resting place of Kazakh historian, Mirza Haider Dughlat, who ruled and was killed in Kashmir.

In Srinagar, Kovtun spent many days of intensely cold January days with Dar’s family who later accompanied her to the Mazar-e-Salateen – the graveyard of Sultans, where they helped her trace the grave of a sixteenth-century Kazakh hero. She took photographs of the epitaphs and inscriptions but could not make much of it. She sent the photographs to Absattar Baghysbaiuly Derbisali (September 15, 1947 – July 15, 2021), the Supreme Mufti of Kazakhstan, who had flown specially to Srinagar at the turn of the last century in his search for Kazakh historian and Mughal soldier. Once the scientist Mufti confirmed it, Kovtun said her teaching has become easy.

“Just dry history, it does not touch your heart,” Kovtun told The Astana Times in July 2015, after her return. “But if you can see, if you visit, if you have the opportunities to go, [this can make history feel alive]. And if you are able to share your emotions and your interest, you are able to touch the hearts of your audience.”

Kazakhstan celebrated the 500th anniversary of the Kazakh soldier in 1998. The government in Astana, the capital of the 19-million-strong landlocked Muslim country, was renamed the Taraz State University after Haider Dughlat. Popularly known as Dulaty University, it is officially M Kh Dulaty Taraz Regional University (M Kh stands for Muhammad Khaider). Dughlat’s statute monument was erected in Taraz city and various streets were named after him in various cities of Kazakhstan.

Kovtun university celebrated her trip. “She went to the place, she was dreaming about for a long time, to the grave of the scientist whose name is mentioned in all her books of the history of Kazakhstan and in historical books of Kirgizstan and Uzbekistan,” a brief note by one of her colleagues reads. “I have to tell you in secret, it was a heavy-duty task: other country, strict traditions of Islam, not stable situation in the region (from time to time news broadcasting about acts of terrorism and religious conflicts there), all that was dangerous for the young lady with a European appearance.”

Kovtun’s journey was just the beginning of a long process involving her country’s embassy in Delhi and the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to repair the grave. By September 2015, Kazakhstan ambassador in Delhi, Bulat Sarsenbayev, now heading an interfaith initiative, flew to Srinagar and initiated the process of repairs. On January 25, 2018, Bulat flew in the company of Absatar Derbisali, and the Rector of Taraz State University named after Muhammad Haidar Dughlat, Makhmetgali Sarybekov to have formal prayers at Dughlat’s repaired and refurbished grave in Zaina Kadal.

The completion of the repairs coincided with a seminar Muhammed Haidar Duglati: The golden bridge between India and Kazakhstan in the Central Asian Studies department of the University of Kashmir. It was the conclusion of a two-year-long process involving obtaining permits for repairs and managing the best hands and drafting the basic information erected near the grave.

The process saw the recovery and repairs of inscriptions. A small but broken white marble stone with Kalima Shahadah inscribed in nastaliq and a Persian chronogram giving the year of his killing. The missing broken part was also retrieved later and restored, albeit after the function was over.

The second inscription was inscribed on a piece of grey limestone. It was a later addition implemented on the orders of a British spy and traveller William Moorcroft by Mir Izzat Ullah Mughal on February 23, 1823. It offers a brief life sketch of Dughlat.

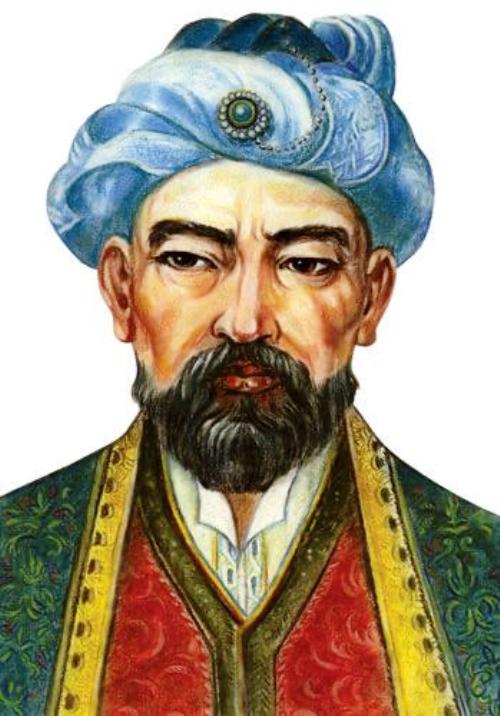

Mirza Dughlat

Dulaty, whose actual name is said to have been Myrza Muhammad Haidar Bon Muhammad Husain Duglat Koregen is a Mughal Kazakh hero because the entire history of Central Asian khanates and Mughals is solely dependent on his magnum opus, Tarikh-Rashidi, a two-volume book on the evolution of Mughal power and the rise of Kazakh state that he dedicated to the son of his benefactor, the king of Kashgar, Rashid Khan.

“He is the single historian who has given us the date of the [foundation of] the Kazakh Khanate – 1465, 1466, according to his description,” historian Kovtun said. “Dughlat described how Khans Janibek and Kerei, the founders of the Kazakh state, left the union of Central Asian tribes created by Abul-Khair Khan and founded their own independent khanate in a corner of modern-day southeast Kazakhstan, on the banks of the Zhetysu River. Some 50 years later, Dughlat was travelling in the region, which was at that time on the border of the Mogul Empire. He met the Kazakh Khan Kassym and took down the history of the then-fledgling state.”

Tarikh-i-Rashidi is an invaluable basic source of information offering details of the rise of Mughal power even before Babur came to India. It offers a detailed account between 1347, Amir Timur days to 1541, the era of Humayun. A personal memoir laced with details of central Asian history, the two-volume book was written by Dughlat between 1541 to 1546, while (mis)ruling Kashmir. It was dedicated and written for Abdur Rashid Khan, son of Sultan Said Khan of Kashgharia, under whose orders Dughlat annexed Kashmir earlier.

Dughlat has clearly mentioned that the book was aimed at preserving the memory of the Mughals and their Khans, which, if not written, could be lost for want of a chronicler. He wrote the second volume, chronicling his personal history from his birth to the capture of Kashmir on August 2, 1541, first, in 1541 itself. The first volume was later done between 1544 and 1545.

An Introduction

Dughlat, according to Bulat, a trained historian, belonged to the first generation of the Mughals, whose ancestors were aristocrats and the tribe lived in the territory of present-day Southern and Southeast Kazakhstan and Kashgar. They succeeded in elevating the Khans to the Mogolistan throne, many times. In gratitude, the Genghis Khan dynasty back in the thirteenth century, during the life of Chagatai (second son of Genghis Khan), transferred to the ancestors of Dughlat tribe the territory of Kashgar (East Turkestan), where they founded a new khanate. When the cousin of Mirza Haidar’s grandfather won the fight for the throne, the loser was forced to leave for Central Asia with his family.

Here, the father of Mirza Haidar, Mohammed Hussain, in about 1492-1493, married Princess Khub Nigar, the third daughter of the ruler of Moghulistan, Yunus Khan. In 1499 she bore him a son –Haidar Dughlat. His birth coincided with Turkic people – Kazakhs and Uzbeks – making efforts to evolve as independent ethnic groups, Bulat wrote.

From the first years of birth, fate was very severe for the future ruler of Kashmir: the boy lost his mother when he was not even two years old. In 1508 Mirza Haidar lost his father (allegedly an expert intriguer), who was killed by order of Shaybani Khan, the Uzbek chief at Herat.

Remaining an orphan, for several years Haidar lived with his cousin, on his mother’s side, Babur (mother of Babur Qutlugh Nigar Khanim was a sister of Khub Nigar Khanim). Tarikh-i-Rashidi suggests that Haider had two younger brothers – Abdullah and Mohammed Shakh, as well as sisters.

Mirza Haidar, Prof Muhib ul Hassan, wrote in his Kashmir Under the Sultan, authoritative history of medieval Kashmir, was carried away to Bukhara by some of his relatives as they felt his life was in danger. From Bukhara he was taken to Badakhshan and thence, after a year, was brought to Kabul where he remained with Babur for two years and accompanied him in his campaigns. Then, in the beginning of 1514, he was summoned by his uncle Sultan Ahmad, the Khan of Mughalistan. Shortly afterwards Sultan Ahmad died, and Mirza Haidar entered the service of Khan’s son, Sultan Sa’id Khan, and remained with him for 19 years, during which he participated in wars against the Kirghiz, the Uzbeks and other tribes.

Dughlat, Bulat wrote, lived in Andijan, where the grandson of Yunus Khan, Abu Said Khan, married his elder sister, Khabib Khanish, and in turn gave his sister to marry him, making him a guragan – the son-in-law of the Khan dynasty. The title, a derivative of the Mongolian word kurugen or hurgen meant he had a relationship with the Genghis Khan dynasty and could freely live and act in their homes.

His Kashmir Entry

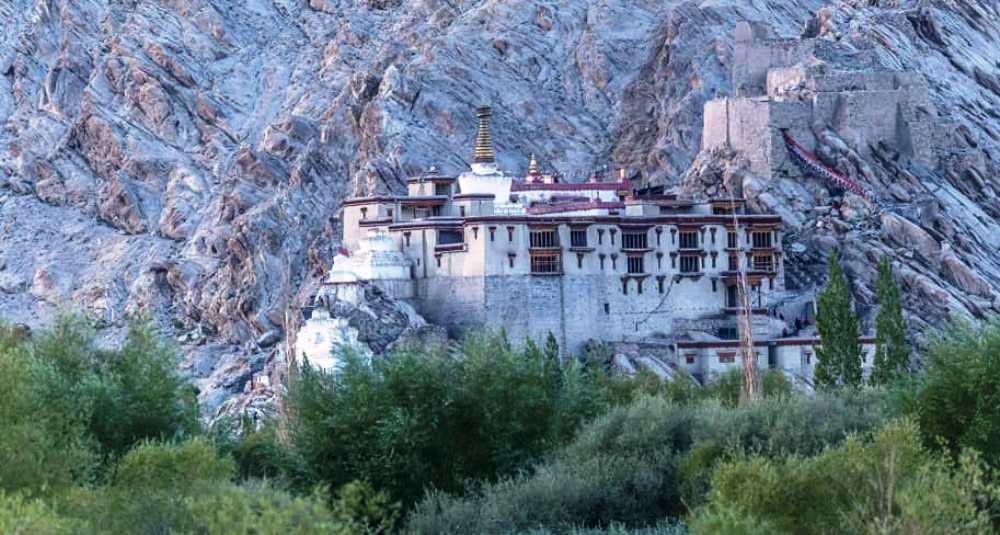

Of all the campaigns, however, it was his Kashmir entry that gave him an enviable status in Central Asian history. Mandated to subdue Tibetans, Dughlat accompanied Said Khan’s second son Iskander in July 1532.

After successfully occupying Nubra, the Kashgar army moved towards Leh when the desert winter started showing up. Retrieving graphic details of the campaign from history, Mohib ul Hassan suggested Ladakh was too small a place to offer food for a 5000-strong army at a time when Iskander was afflicted by damgir (apparently breathlessness which is a high altitude sickness owing to Oxygen depletion). They bifurcated the army with Iskander taking 1000 soldiers and conquering Baltistan and Dughlat moving with the rest to Srinagar.

Dughlat crossed the Zoji-La and entered Kashmir early in January 1533. He dispatched 400 special troops under Tuman Bahadur Qabuchi, whose surprise assault led to the desertion of the Kashmiri army at Lar (Ganderbal). Frustrated, the reserves fled to Hanjik (Budgam) and Dughlat marched on Naushahr (Srinagar) the seat of medieval governance and took over the Rajdan, the secretariat palace built by Budshah.

“After staying there for 24 days he proceeded towards Maraj (Maraz). His followers set fire to the villages and towns and destroyed the grand edifices built by the former rulers of the country,” Muhib wrote. “They massacred the men and made the women and children their slaves. They made no distinction between Muslims and non-Muslims.”

The campaign continued till March and most of the population fled to the mountains. The Ulema also fled and took refuge in the Wullar lake island wherefrom they issued a fatwa asking residents to resist and fight. This started making a difference.

Malik Ali Chadura evolved into the key resistance leader. He engaged Dughlat’s commander Bab Sharq Mirza in a serious attack in Bagh-e-Bava, a south Kashmir medieval hamlet located on the Martand plateau. In retaliation later, Malik Ali was assassinated.

It was the turn of two Kashmir nobles Kaji Chak and Abdal Magre to takeover. Instead of a direct confrontation with the invader, they decided for a guerrilla way-out. They would descend from hills, and resort to hit and run, which gradually wore invaders down.

Dughlat was so harassed that he consulted his confidants to devise a strategy. There were two schools of thought. Mir Daaim Ali, according to Muhib’s probe, suggested his master attack the high-altitude bases, destroy the resistance and consolidate the control. Mirza Ali Taghai, opposed the idea as it would destroy Mughal troops. Instead, he suggested their families living on the plains be attacked. “This would be that those whose families were in the Valley would come down to defend them, while those whose families were on the hilltops would remain behind. Thus the enemy forces would be divided, and

they could then be easily overpowered,” Mohib wrote. As this strategy failed, the army started to support the idea of leaving Kashmir.

Finally, Dughlat got into negotiations, ensured the khutba be read in the name of Said Khan, took Kashmiri noble Muhammad Shah’s brother’s daughter in the marriage of his Prince Sikandar Sultan, and collected presents for his Kashgar master and took the same route back by the end of May 1533.

State In Mess

A devastated Kashmir expectedly fell into chaos and drought. Kashmir nobles helped people fight starvation to prevent a civil war. Given the internecine tensions, Kashmir could not stay peaceful for a long time. In 1537, Mohib wrote, that when Kashmir ruler Muhammad Shah died, his second son, Shamsuddin took over and it triggered a civil war.

Unable to see Magres and Regi Chak supported Shamsuddin becoming Kashmir’s new master, Kaji Chak moved with his army from Zainpora forcing the former to take refuge in Baramulla. However, Kaji’s ally, Daulat defected to the ruling side, forcing him to leave Kashmir and take refuge in Punjab. A year later in 1538, when Regi proceeded to Jammu to solemnise his marriage with the Jammu ruler, Kaji attacked Kashmir from Baramulla and his allies finally took control of Kashmir. Though just and efficient, Kaji was destined not to be in power for long.

Dughlat had not gone home. Soon after getting a safe passage out of Kashmir, his Kasghgar master died and his son, Rashid had taken over. After assuming power, Rashid started culling all the people who were supporting Iskander, his brother. Knowing his association with Iskander, Dughlat avoided his return – barring a brief visit to Badakhshan, and busied himself in conquests on the Tibetan plateau. He later moved to Lahore, worked for Karman and later joined Humayun. It was during his Lahore sojourn that the Kashmir opportunity came knocking at his door.

The Second Attack

Dispossessed, Abdal Magrie and Regi Chak hired Khwaja Haji as their agent who approached Dughlat to help in wresting power from Kaji. There were no takers. Instead, Dughlat accompanied Kamran to Agra, where an army was raised to accompany Haji to Kashmir. Its commander, Baba Jujak was a coward who moved to Lahore and halted. Even as their Kashmir allies were waiting in Rajouri hills, Baba abandoned the campaign after Humayun was defeated by Sher Shah Suri on May 17, 1540.

The diplomacy was revived. Banking on assurances that Kashmir will fall within two months, this time, Dughalt offered to move personally. The pressing need was to find refuge for Mughal families – women and children, and Kashmir had emerged as the best destination. Kamran, however, suggested women should be sent to Kabul and men should take refuge in the Kashmir mountains.

As the leader of 400 soldiers, Dughalt reached Nawshehra and was joined by his allies. Even Humayun had reached Nawshehra on his way to Kashmir in October 1540 but later decided not to get in. In Srinagar, Kaji was in a panic. He moved with his army to block Kapartal Pass. Dughlat, however, had abandoned the route and used Punch Pass to get into Kashmir on November 22, 1540. It was the smaller ever army in history that conquered Kashmir without even, as Mohib recorded, “striking a blow”.

Kaji and his allies did not return. They left the country and started seeking support from Sher Shah. He did give him 5000 soldiers that marched into Kashmir in 1541. After a standoff of two months, 5000 Chak soldiers fought with 3000 strong Dughlat army at Watnar on August 13, 1541, in which the former lost.

Dughlat Rule

After appointing Nazuk Shah as a titular ruler, Dughlat, Mohib has written divided Kashmir into three equal parts between himself, Abdal and Regi. Abdal died a year later. Taking lessons from his earlier experience, Dughlat made peace with nobles, even those who opposed him.

Historians have been very kind in appreciating Dughlat’s efforts in reviving arts and crafts. A “great admirer” of Budshah, the poet-writer Dughlat patronized men of learning, and appointed teachers in every village for educating children, built mosques in Srinagar with baths and ensured they stay warm in winter; constructed magnificent edifices, and laid out beautiful gardens in Andarkot; introduced new types of windows and doors, and made innovations in dress and

food. Great music lover, he introduced central Asian instrumentation and encouraged penmanship, painting, and handicrafts.

“During his 11-year reign, Dughlat brought about three thousand artisans, who, on his orders, erected many objects in the style of architecture of East Turkestan. As a poet, he made a great impact on the development of the cultural component,” Bulat wrote. “At the same time, the scientist changed the local cuisine, introducing dishes of his homeland into it.”

Soon, however, his arrogance dominated his statecraft and he started ignoring the nobles. Regi, his ally was the first to resent his attitude. The gulf widened so much that in 1543, Dughlat led his army to Kamraz (north Kashmir) to seize Regi but the latter had fled to Rajouri and joined Kaji Chak. Angry, he razed his palace to the ground before returning to Anderkot palace.

In 1544, Regi and Kaji, the strange bedfellows moved into Gulmarg but were defeated, following which Kaji died on September 12, 1544, at Thana (Poonch). In 1546, when Regi invaded, his army was defeated and his head was taken as a trophy to Dughlat’s court. Though Dughlat was de facto ruler, he retained Nazuk as titular king in whose name the Khutba was read and coins were struck. Confident of his possession, Dughlat attempted to take over Kishtwar in 1548, but so much of casualties were inflicted upon his army at Dar village that it is still known as Mughal Mazar. However, he succeeded in retaking Baltistan, Ladakh and Rajouri and appointed Mulla Qasim, Mulla Baqi and Muhammad Nazar as governors, respectively.

In 1549, Mohib has recorded, Dughlat became a target of huge extortion at the hands of Haibat Khan Niyazi, the governor of Lahore. Though he made peace at huge costs, he could not mend his fence within the Kashmir population, especially the Nurbakhshiya sect (Shia). This was despite the fact that to please Regi and his other Shia nobles, Dughlat once visited and paid respects at the mausoleum of Mir Shamsuddin Iraqi. Provoked by his fanatic court members, Dughlat banned Shias and even destroyed the tomb.

In 1545, he killed Hazrat Rishi, Sufi Daud, and Mulla Hajib Khatib, and exiled Qazi Mir Ali after their houses were destroyed. Shaikhi Daniyal, son of Iraqi had fled to Skardu where he was captured, imprisoned in Srinagar and eventually executed on basis of false witnesses accusing him of reviling the first three Caliphs.

“The execution of Daniyal was a great mistake committed by Mirza Haidar because he was a pious man and much respected in the country,” Muhib has recorded. “The Mirza had been warned by Mulla ‘Abdullah, one of his confidants, against this step, but he had ignored him replying that Daniyal’s execution was necessary for the stability and welfare of the kingdom.”

The End

Angry, his opponents won over Nazuk and company and efforts started to overthrow him. In 1551, Kashmir hills broke in unrest and Dughlat sent mixed contingents of Mughals and Kashmiris under Qara Bahadur to Manjkot (there are two villages with the same name on either side of the LoC), where they were decimated by Kashmiri rebels. They attacked the Barbal fort (near Tosamiadan) and killed the royal troops. Those surviving were caught and their arms were cut. Later, all Kashmir nobles came together to Kashmir under Idi Raina to give the last push to Dughlat’s fall.

Kazakh and Kashmiri historians differ in recording Dughlat’s end. “Around the death of Mirza Haidar there is still a lot of obscurities,” Bulat wrote. “However, according to the well-established version, he was accidentally killed by the arrow of his warrior in 1551 during clashes with the mountain tribes of Kashmir. He was buried here with great honours.”

Mohib ul Hassan has relied hugely on Syed Ali, the author of the Persian chronicle, Tarikh-Kashmir, who was not only the witness of happenings but also in Dughlat’s service. Kashmir uprising coincided with similar unrests in Ladakh, Baltistan and Pakhli (Hazara). Most of his governors were killed. Frightened, Dughlat moved his family to Andarkot palace and then left for Vahator (perhaps Wathoora) to engage with Raina, who had fortified himself in Manar fort at Khampur, 10 km from Srinagar on the Pir Panchal pass. He ignored the counsel of his colleagues and nominated his brother Rehman as his successor.

“He marched against the enemy with about 700 or 800 horses. When he reached the base of the fort he left his troops behind, and with only thirty men proceeded to the top of the buttress,” Mohib recorded. “But on the way, most of his followers fell out, and he was left with only seven men. While he was trying to enter the fort, he was killed by an arrow.” It was October 1551. Mohib has trashed all other alternative narratives about the death, insisting they are hearsay.

“There may be some truth in the tradition contained in the Tabaqat-i-Akbari that, while he was leading the attack, Mirza Haidar was accidentally struck by an arrow discharged by Shah Nazar, a cuirassier, belonging to his own army,” Mohib wrote. “This statement does not in any way conflict with that of Sayyid Ali, who is silent over the question of whether Mirza Haidar lost his life at the hands of the enemy or one of his own men.”

Safe Passage

People who were keen to insult Dughlat’s body were prevented from doing anything and the body was laid to rest in Mazar-e-Salateen, the royal graveyard, not far away from Budshah’s grave. A guard remained posted at the grave for a month to prevent desecration.

Andrakot remained under attack for three days till Dughlat’s widow sent her confidant, Amir Khan to negotiate her surrender. “Qara Bahadur and others who were in prison were released. The Kashmiris gave an undertaking that they would not molest the family and followers of Mirza Haidar,” Mohib recorded. “After this, his family was brought from Andarkot to Srinagar and treated with respect. They were then sent via Pakhli and Kabul to Kashghar.”

Still relevant

Unlike many other Mughals, Dughlat remains relevant to history. Kazakh’s treat him as their hero who has immensely contributed to building the edifice of their ethnic narrative. Even in India, he is a key connection between Delhi and Astana (now Nur Sultan), the Kazakhstan capital.

“Ties between the countries date back more than 2500 years when members of the Saka tribes travelled to India and established mighty empires in the North West of the country. There has been a constant and regular flow of trade in goods and, more importantly, free exchange of ideas thought and philosophy through the Great Silk Route in the 5th -12th Century AD. This period also saw the introduction of Buddhism from India to Kazakhstan and the travel of Sufism through the teachings of Khwaja Ahmed Yassawi to India,” Ashok Sajjanhar, former Indian Ambassador to Kazakhstan wrote in a detailed piece tackling the bilateral relations. “Babar’s illustrious Mughal dynasty which included farsighted and visionary rulers and patrons of arts like Akbar and Shahjahan

immensely contributed to the Indian civilization. Simultaneously, rulers and scholars like Mirza Haidar Dughlat left their indelible imprint on regions like Kashmir which they ruled for several years.”

Kazakhstan, Central Asia’s major economy, is India’s major trade partner with bilateral trade about to touch US 1.5 billion.

“Dughlat until the end of his days did not give up hope to return to the homeland of his ancestors, which was located on the territory of present-day Kazakhstan,” Bulat wrote. “His journey back to his homeland was long and difficult. But he returned, enriching the spiritual and historical treasury of the Kazakh people.”