As lockdown restricted people to their homes, hairy individuals are desperate to unburden their skulls. The added tensions are that the hair-styling sector has already been taken over by the skilled non-locals, most of whom are home in the plains, reports Masood Hussain

In Drass, at the peak of the 1999 war, when the population had deserted Drass, the main war front, those staying back were some vegetable sellers, two dhabas and barbers. Last month, when France opened after six weeks, it was not food joints but the salons that witnessed unprecedented crowds. Both men and women swarmed the salons because the lockdown had de-shaped their styles. Hair croppers, one of the oldest human professionals, provide the key basic facility.

In Kashmir, where mostly men require hairstyling, the situation is pretty precarious. Primarily, people are scared of barbers and hairstylists. If they wish to move out to find hair-styling joints, they would not find many actually in business, right now.

Early May, it triggered panic in Handwara’s Gonipora belt when a barber tested positive for Covid-19. The particular barber had been routinely visiting his customers and even inviting some to his place. It was a painful exercise for the concerned officials to trace his contacts so that the necessary precautions are taken. Thankfully, not many of them were found infected.

In neighbouring Baramulla, another barber came on the radar for having cut the hair of a person who tested positive for the viral disease. He, along with many of his contacts, was sent on home quarantine. Thankfully, one youngster who also was on the radar said, the barber tested negative, so did many of his contacts. In fact, the Covid-19 patient also tested negative twice and is apparently out of danger.

These incidents have prevented people from seeking the services of these professionals. In most cases, people used the tools available at home or in the locality to stay in better shape. All of a sudden there was a huge demand for trimmers. In most of the cases, it was either self-help or the families chipping in.

But it has not altered the demand side much. As one person wrote on Twitter that the government should add barbers in the essential services list, otherwise “har ghar say Omar Abdullah niklay ga”.

When Omar Abdullah eventually moved out of the Hari Niwas Palace converted into a sub-jail for him, he wore a flowing salt and pepper beard. In a quick follow-up, his Twitter fans got into a snap poll over his beard as a division emerged on whether Omar should restore his facial status quo ante or not. The poll suggested he must wear his beard and he obliged them.

But nobody knew that the Covid-19 lockdown will be so widespread and protracted that the hair-setters will shut their shops and the authorities will enforce a strict curfew – to the extent of arresting and registering cases for violators, resulting in people getting too much hairy.

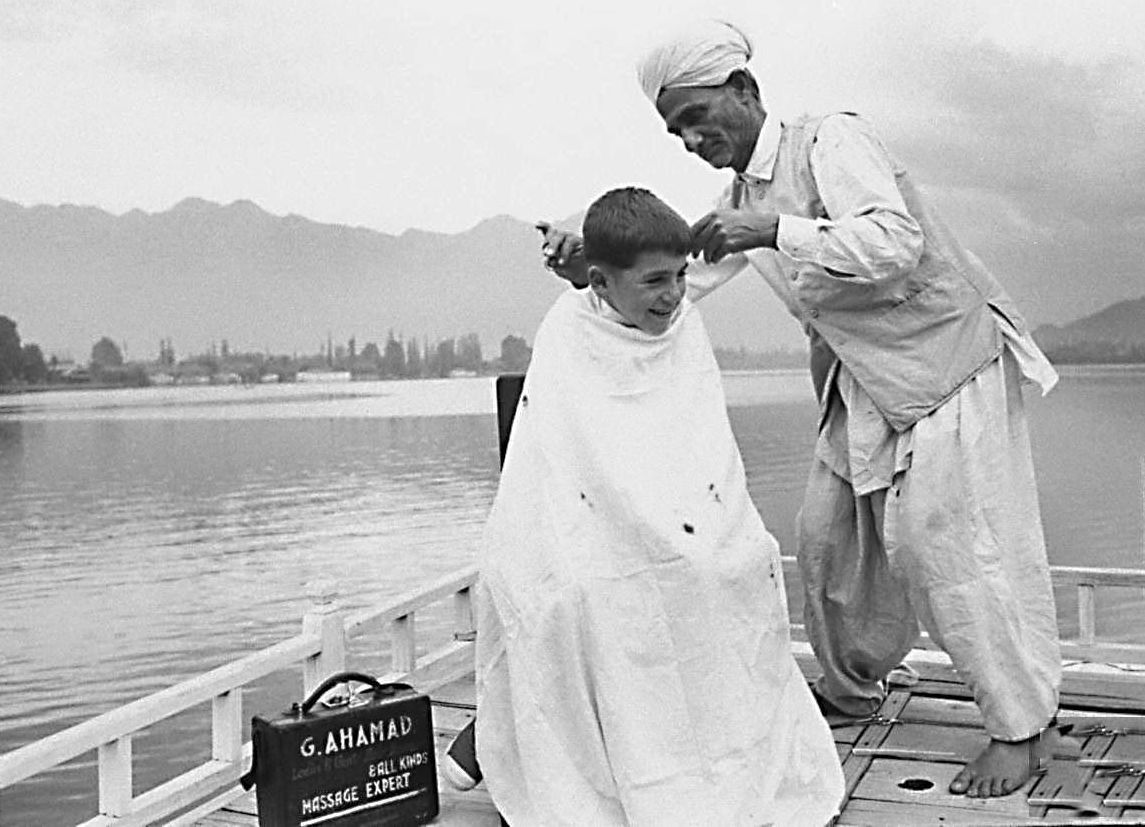

PHOTO BY BILAL BAHADUR

Over the years, hair cutting has evolved into fine art. For most of Kashmir’s history, the barbers were professionals who usually did not own lands and would move from door to door for offering their services. Unlike the urban spaces, they would offer their services to a belt and collect their numerations at the time of the harvest. It was sort of barter, they provided the services and were paid in paddy to feed their kitchens.

They would usually remain in the lower rung of the society’s socio-economic stratification even though they would offer a lot of services from managing certain ailments to preparing the grooms. Their low income was the key factor in forcing most of them to switch over to other professions, gradually acquiring small pieces of land, getting into the government services and opening their salons as per the local requirements.

In the last thirty years, this sector exhibited a massive shift. Part of the contributing factors was the mass conversion of the paddy fields into the apple orchards in most of Kashmir. With the landowners themselves purchasing the rice from the open market or the government-run ration depots, the barbers – like iron-smiths, and even the faith-healers, quitted their age-old style of operations. They would only go to the elite and the commoners would have to travel to their shops.

As the connectivity improved, hundreds of barbers came from mainland locations and took the sector to a new level. In this competition, the traditional barbers lost the market. Already facing a crisis in the social order, some of them quit their professions and moved to other sources of income. Gradually Kashmir started depending hugely on the non-local barbers, especially in the urban and suburban spaces.

These migrant skilled persons, mostly Muslims from India’s marginal minority, found Kashmir suited for them given a cultural affinity. They, however, had their own problems in managing their operations in a hugely fragile society. Though they managed their operations well for most of the turmoil, they had upsetting times during the mass unrests in 2010 and 2016. But the worst situation came in August 2018 when in anticipation of the August 5 decision making – the Government of India rolled back the special status. The government ordered all of them to move out. Some of them tried to stay put but the society saw them with suspicion because the new law promulgated by the Parliament indicated the rollback of the protection to the demographic composition of the state. Most of these professionals moved home.

A month after the state government-sponsored flight of the non-locals from Kashmir, the Indian Express visited Kirtapur towns in Bijnor and talked to the people who were running Kashmir’s hair-styling show. Nobody gave them their names but they talked in detail. A 32-year old said he has been working in Kupwara for 15 years and makes a monthly earning of Rs 15 to Rs 20,000. In the Bijnor district, the number of families working and living in Kashmir is 2000. Of them, the newspaper said 100 families were from Kirtapur alone.

The newspaper tracked Bijnor’s Kashmir’s connection to the 1960s when two men, Ghulam Mustafa and Rashid, landed in Bhopal, wherefrom they were hired to work in ‘the city to Kashmir. “Later, they returned to Bijnor and took youngsters with them there,” the newspaper reported.

In anticipation of August 5, 2019, when the migrant barbers left, the market suddenly felt the appetite for the service in the protracted shutdown. They are running an estimated 20,000 salons and shops across Kashmir, according to Kashmir Hairdressers Association. The gap was filled by the local barbers, some of whom had actually switched over to other professions.

Shaban had quit as a hair-cropper to become a labourer almost 12 years back. As the migrant barbers fled, he told The Telegraph that he was “flooded with requests to reopen my shop”. Locals helped him dust and reorder his abandoned salon. “I’m making good money, more than what I earned as a mason,” Shaban said.

However, it was a temporary phase as most of the barbers could not stay home for a long time because they could not find many opportunities around in UP. Most of them returned and restarted their businesses. But that phase was also temporary. As the Covid-19 arrived, most of them had to rush home. Some of them are still staying put. But the situation is not conducive for them to operate normally as the lock-down, now in the third month, is being strictly implemented.

“Barbers who are settled here and here,” Fayaz Ahmad, who lives in the old Srinagar city, said. These people who have been working here for the last 20 years or more have their kids enrolled in local schools. Some of them have hugely invested in their salons. “They are going from door to door to trim the hair of the people.”

At individual levels, people are also using scissors, clippers and trimmers to keep their hair in check. On social media, there were a lot of photographs showing the people cutting each other’s unkempt hair to stay in order. The families faced tensions because of the children. Traditionally, the kids go for hair-dressing in anticipation of the Eid. This time, however, they had only two options – to either undergo a haircut by their parents or simply wait. The wait is only getting longer.